Summary

- In the past three years, a combination of civil war, political turbulence and territorial rivalry has transformed the political economy of the sesame sector in Ethiopia and Sudan. The industry is no longer just a mainstay of local livelihoods in the borderlands between the two countries. It now plays a central role in a transnational conflict economy that perpetuates violence and political instability.

- This research paper charts these dynamics, exploring their drivers and impacts. It focuses on how different actors – including government armed forces, local elites, and militias and rebel groups in border regions – have competed for control of farmlands, sesame production and trade. The paper also proposes solutions that might help to reduce violence and promote stabilization by addressing internal and transnational conflict dynamics affecting Ethiopia and Sudan.

- Contested access to land and economic resources continues to fuel and sustain conflict in both countries. It has been a major factor in two destructive civil wars: in Ethiopia (2020–22) and Sudan (2023 to the present) respectively. Related pressures have also inflamed a cross-border dispute between Ethiopia and Sudan over Al Fashaga, a major sesame-producing region. These conflicts and crises have developed complex transnational dimensions, involving contradictory interests from neighbouring countries as well as other external actors.

- The sesame sector has become a focal point in the region’s troubles. Although sesame is in many respects an unremarkable agricultural crop, its value as a staple of local economies and livelihoods means that it has become in effect a strategic ‘conflict commodity’ – one that is embedded in local, subnational and national political contestations, and in turn implicated in the transnational conflict dynamics mentioned above.

- Local communities have been disrupted in numerous ways. Violence along the Ethiopia–Sudan border, and internally in both countries, has had redistributive and transformative economic effects. It has created new power-holders, and thus political and economic winners and losers. Where certain groups have captured the production and trade of resources such as sesame, they have used this to entrench political and territorial control. For example, the Sudanese army has fortified its military and economic control of border areas in Al Fashaga, capturing profits from the sesame trade to sustain its war effort. This has had harmful consequences for local Sudanese and Ethiopian farmers. Further to the east, contestation of territory in Western Tigray/Welkait has reinforced ethnic fragmentation. The displacement of local farmers and investors by Amhara elite interests has resulted in a shift in the ‘identity’ of the land from Tigrayan to Amhara.

- The recommendations in this paper are aimed at both domestic and international policymakers. The authors emphasize the need to consider the political economy of conflict, as well as related subnational and transnational dynamics, when developing plans for conflict mitigation and management. The implications of turbulent political transitions in both Ethiopia and Sudan also need to be factored in. Among its specific recommendations, the paper calls for policymakers and development partners to:

- Understand and address the transnational dynamics that trigger armed conflict. Conflict resolution cannot be considered a purely domestic matter for each country, but needs to navigate interests on all sides, some of which are often far beyond national borders.

- Pay attention to the economic aspects of conflict. Conflict resolution efforts should factor in the intersection of conflict with issues of political economy in both countries, including the external economic interactions that facilitate conflict.

- Broaden definitions of ‘conflict goods’. A legal and seemingly innocuous commodity such as sesame can generate conflict. Policymakers need to understand that conventional definitions of conflict goods – for example, illicit minerals, weapons or drugs – are inadequate on their own for informing peacebuilding and reconstruction programming in the Ethiopian and Sudanese contexts.

- Think beyond ‘licit’ and ‘illicit’. Smuggling is often a necessity for borderland communities due to the lack of alternative livelihood options and to impediments placed on trade by state and non-state actors. Trade outside official channels can be a vector for community survival and resilience. Policymakers should show a degree of flexibility in tolerating informal trade; they should support the regularization of trade in licit commodities because of the necessity of such trade for everyday existence.

- Foster ‘bottom up’ initiatives. There is a long history of local cohabitation and collaboration across the Ethiopia–Sudan border. It will be important for development partners to support the establishment and strengthening of engagement and relationships at subnational and local levels. This effort should include introducing cooperative cross-border measures that build trust, including collaborative farming and trade of sesame.

- Acknowledge the impact of regional relationships and external influences. Political alignments in the Horn of Africa continue to shift, partly as a consequence of a reshaping of the regional political order since 2018. Regional and international policymakers will need to accommodate this repositioning in their thinking, and in their engagement with all relevant parties, to prevent insecurity from worsening in and across border areas.

- Provide support for multilateral or external dialogue and mediation. There is a pressing need to prevent border tensions between Ethiopia and Sudan from escalating, as this would worsen protracted instability in both countries. It is vital for policymakers to understand which states or multilateral bodies are best placed to be effective mediators, and which are not.

In the context of civil war and related political turmoil, sesame farming is no longer just a mainstay of local livelihoods in the borderlands between Ethiopia and Sudan. It plays a central role in a conflict economy that perpetuates violence and political instability.

Over the past three years, civil wars and territorial tensions in Ethiopia and Sudan have profoundly destabilized communities along the 740-km border between the two countries. This has not only created security and humanitarian challenges directly associated with military action, but has also disrupted patterns of local land ownership and control, and sustained a conflict economy around the production and trade of oilseeds such as sesame. These cash crops have long been economically vital to both Ethiopia and Sudan, and competition to control sesame revenues from the regions bordering the two countries has both reshaped local agricultural markets and provided a strategic motivation for conflict participants and members of political and economic elites.

The trigger for these economic changes occurred in late 2020, when a destructive two-year civil war started in Ethiopia’s northern region of Tigray (see Chapter 2). This conflict, between Ethiopia’s federal government and the Tigray regional government, also involved fighting for control of territory between forces from Amhara and Tigray, two of the 12 regional states under Ethiopia’s federal system. However, the situation was soon complicated by two factors that had the effect of immediately regionalizing the war: first, the involvement of the Eritrean army, allied to the Ethiopian federal government and Amhara forces against the Tigrayans; and second, the incursion in December 2020 of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) into the disputed area of Al Fashaga on the Ethiopia–Sudan border. Although hostilities in Tigray itself ended with the signing of a tenuous ceasefire (the ‘Pretoria Agreement’) in November 2022, both territorial disputes – that between Amhara and Tigray, and that between Ethiopia and Sudan over Al Fashaga – remain unresolved.

Regional stability was also soon undermined by a new conflict. In April 2023, war broke out in Sudan between the country’s two most powerful military forces, the SAF and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). While the war has not yet directly engulfed sesame-growing areas along the border, it has fragmented Sudan. The SAF-led military regime has consolidated its control in eastern Sudan, making the area more vulnerable to militarization and future shifts in the trajectory of the conflict, while also disrupting the political economy.

The implications for rural livelihoods in northwestern Ethiopia and eastern Sudan, both centres of sesame and oilseed production, have been significant. In many respects, sesame is an unremarkable agricultural product like many others, yet it has in effect become a strategic ‘conflict commodity’ – one that is embedded in local, subnational and national political contestations, and in turn implicated in transnational conflicts.1 Value chains for sesame production have been reshaped, with profits helping to entrench the power of political and armed actors, reinforcing new patterns of land control, and driving informal and illicit trade.

Over the past three years, civil wars and territorial tensions in Ethiopia and Sudan have profoundly destabilized communities along the 740-km border between the two countries.

These dynamics have continued to fuel competition and conflict among the political and business elites in both countries. The transformation of the sesame sector, and its appropriation by armed actors and special interests, is undermining the livelihoods and resilience of local communities. Changes in territorial control have led to the large-scale displacement of local people. Local investors have also been negatively affected by militarization and the loss of land holdings or related income streams. If not addressed, all these shifts threaten to prolong and intensify conflict and the inequalities faced by people living in these areas.

About this paper

The research paper outlines the ways in which the sesame industry is connected to, and interacts with, both internal and transnational conflict dynamics affecting Ethiopia and Sudan. The paper first examines the transnational nature of recent or ongoing civil war in both countries, before exploring the economic and strategic importance of sesame as a commodity, and its role in shaping cross-border relationships – notably in relation to the disputed territories of Western Tigray/Welkait and Al Fashaga.2 The paper goes on to examine the dynamics driving Ethiopian and Sudanese elite competition respectively. It analyses the perspectives and policies of different military and political factional interests in relation to sesame production and trade, control of agricultural lands, and the status of shared borderlands. The paper also explores how violent conflict has had wider redistributive and transformative effects, creating new power-holders, and thus political and economic winners and losers, in each region. Our analysis emphasizes the point that resource sectors such as sesame – when captured by certain groups, including national armed forces, rebel militias and economic elites – can be used to fuel conflict.

The paper concludes by offering recommendations for effective policy interventions that might help to address internal and transnational conflict dynamics affecting both countries. Some recommendations are aimed at policymakers in Ethiopia and Sudan, while others are meant for regional and international partners supporting stability in both countries and across the Horn of Africa. The latter include the EU, the UK and the US, along with multilateral bodies such as the African Union (AU), the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and the United Nations (UN).

Our recommendations emphasize the need to consider the political economy of conflict, as well as related subnational and transnational dynamics, when addressing conflict management and mitigation in a context of turbulent political transitions in both Ethiopia and Sudan. As a consequence, the conclusions of this paper also seek to inform multilateral institutions’ existing cross-border programmes and projects, including the African Union Border Programme (AUBP), IGAD’s cross-border initiatives and the United Nations Development Programme’s Africa Borderlands Centre.

Methodology

This research paper is part of the Sudan borderlands case study investigated by Chatham House for the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research programme.

The paper is based on field-research conducted in Ethiopia and Sudan between late 2020 and early 2023. In Ethiopia, primary data collection was conducted in Addis Ababa and Amhara regional state (Bahir Dar, Gondar), as well as in the contested territory of Western Tigray/Welkait. In Sudan, data collection was conducted in Khartoum, Gedaref and Kassala states.

The bulk of field research consisted of semi-structured key informant interviews, conducted in person and by phone. The research was also underpinned by data collection and analysis commissioned by XCEPT for Chatham House, including quantitative data collection on the local economies of eastern Sudan and Western Tigray/Welkait by Emani and satellite and signals data analysis by Satellite Applications Catapult and Vigil Monitor. Desk-based research examined a variety of secondary sources, including academic and policy research on both countries and their local and regional dynamics, official documentation, trade data, and news sources from Ethiopian, Sudanese and international outlets.

The sampling for the interviews sought to represent a broad range of actors and interests engaged in the political economy in both countries and the focus localities of this study. This included government officials (at national and local levels), members of armed groups, regional and international diplomatic actors, academics, policy analysts, businesspeople, farmers, and civil society representatives. The sample also included representatives from Western governments and multilateral organizations. A limitation of the study was not conducting research in other parts of the broader region, such as Eritrea, Egypt or the Gulf states.

Due consideration was given to the safety of the researchers and the potential research participants. The political and security situation in parts of Ethiopia and Sudan meant that not all actors could be consulted and not all societal positions could be included. For example, it was not possible to conduct focus group discussions with local farmers and workers in the sesame sector as the authors had originally intended.

02 The transnational nature of conflict in Ethiopia and Sudan

Civil wars in Ethiopia and Sudan have developed complex transnational dimensions, involving rival interests from both countries, as well as external actors. These conflicts are largely fuelled by competition over economic resources and land.

The eruption of two devastating wars inside three years in neighbouring Ethiopia and Sudan has been the consequence of an ongoing reshaping of the previously dominant political orders in both countries since 2018, including contestation over the wider regional order which these regimes had in effect built over many years.

Through regimes that controlled each country for nearly three decades – the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) and Sudan’s National Congress Party (NCP) respectively – Ethiopia and Sudan evolved to become the dominant states in their region. In each case, domestic policy was closely connected to that regime’s foreign policy. This shaped a regional system in which Ethiopia and Sudan, in their separate ways, successfully sought to influence the political, security and economic affairs of smaller neighbouring states: Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia and, latterly, South Sudan.

As a result, recent and/or ongoing conflicts – whose effects remain acutely visible in both Ethiopia and Sudan today – have consequences not only for the two countries’ bilateral relations, but also for wider transnational dynamics. In particular, the fallout from the Ethiopian and Sudanese wars risks creating instability in the Horn of Africa and increasing that region’s susceptibility to harmful influence from external actors. Such influence notably could include securitized responses by states in the Middle East and North Africa region.

War in Ethiopia and its transnational dimensions

Ethiopia’s civil war, which started in November 2020, led to hundreds of thousands of deaths and the displacement of over 2 million people in the country’s northern states of Tigray, Amhara and Afar. The war ended after Ethiopia’s federal government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), two of the principal belligerents, signed the Pretoria Agreement in South Africa in November 2022.3 However, the damage to Ethiopia’s societal fabric will last for generations given the widespread atrocities committed – including alleged war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing – during the war by Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF), Eritrean defence forces, and regional forces from Amhara and Tigray.4 This war is also one of the main drivers of the deepening conflict in the Amhara region.

The war evolved into a regional conflict involving divergent interests both from neighbouring countries and from further afield.5 Eritrea has been the most directly involved external country, sending its forces into Tigray to fight alongside those of the Ethiopian government and allied Amhara regional forces during the war, and maintaining troops and territorial control in parts of Tigray even following the Pretoria Agreement.6 The Eritrean government also used the war as an opportunity to seize land, to which it had long held claim, along Eritrea’s border with Ethiopia. Although some of this land had already been delimited in Eritrea’s favour by the Eritrea–Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC) in the 2002 Algiers Agreement, Eritrea’s recent encroachment into and seizure of territory have gone beyond the areas stipulated by the EEBC.

Eritrea has also sought to develop its relations with Ethiopian subnational ethnic groups, in particular the Amhara and Afar, in part to guard against a possible deterioration of relations with Ethiopia’s federal government, a risk that has subsequently materialized. This has had consequences for one of the most contentious issues still to be resolved following the end of the 2020–22 war in Ethiopia: the status of areas contested by both Amhara and Tigray, most notably Western Tigray/Welkait. This disputed region was taken over by Amhara forces at the beginning of the war. The interim Tigrayan authorities have been calling for its return to Tigrayan control, as provided for under the conditions of the Pretoria Agreement. The Ethiopian federal government’s position is to hold a referendum on the status of the contested area after facilitating the return of internally displaced persons (IDPs).7

Ethiopia and Sudan have long been competitors within the Horn of Africa region. Their governments have a history of interfering in each other’s affairs and supporting armed groups opposed to the incumbent regime of the other country. Following the outbreak of war in Tigray in late 2020, the SAF moved to occupy the contested border territory of Al Fashaga, an agricultural heartland crucial to sesame production. This move led to a significant deterioration in relations between the two national governments. Ethiopia asserts that Sudan provided weapons to the TPLF during the fighting. Regardless of the facts behind this allegation, Sudan did provide refuge to certain high-ranking TPLF members,8 as well as shelter for 60,000 Tigrayans who fled into eastern Sudan.

Relations between Ethiopia and Sudan are now being shaped further by the war in Sudan between the SAF regime and the RSF paramilitary group.

Relations between Ethiopia and Sudan are now being shaped further by the war in Sudan between the SAF-led military regime and the RSF paramilitary group. Ethiopia’s prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, has so far sought to stay impartial and avoid inflaming tensions over border disputes. He has also contributed to efforts by IGAD heads of state to mediate between the warring parties. However, Sudan’s military regime has distanced itself from these efforts, and has sought to paint some of IGAD’s members, including the Ethiopian and Kenyan governments, as sympathetic to the RSF.

Given the recent history of antagonism between Ethiopia’s government and the Sudanese military regime, Ethiopia could see value in the RSF gaining the upper hand in Sudan, particularly if the latter is amenable to Addis Ababa’s position on issues of bilateral dispute, including the border and the operation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). The GERD is also a critical object of contention between Ethiopia and Egypt, which has influence over the SAF.

The possibility of the Ethiopian government overtly supporting the RSF would have to be weighed carefully in Addis Ababa, given the likely reputational consequences, and the current overall military stalemate does not make such an outcome likely. Cooperation may also be facilitated by Ethiopia’s strong ties with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the RSF’s main backer. The UAE provided pivotal military support to the Ethiopian government during the Tigray war, and also has substantial investments in Ethiopia’s economy.9 Should the Ethiopian government’s position on the war in Sudan shift in favour of the RSF, it would likely be influenced by the UAE to some degree, and this would represent another example of the outsized role the Gulf state has been playing for almost a decade in shaping developments in the Horn of Africa and elsewhere on the continent.10

War in Sudan and its transnational dimensions

The war in Sudan has raged unabated for almost a year. The devastation wrought since April 2023 has led the country to the brink of fragmentation and created one of the world’s biggest displacement crises. Around 6.5 million people have been internally displaced, while nearly 2 million have fled to neighbouring countries – the majority to Chad, Egypt and South Sudan.11

The conflict between the SAF, led by Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the RSF, led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (known as Hemedti), is driven in part by competition for power and resources and is fast evolving into an ethnicized war. A de facto partition of Sudan has emerged. As of mid-March 2024, the war was largely deadlocked. The RSF controlled much of the capital, Khartoum, and west of the country, and had expanded its footprint in the centre. The SAF, meanwhile, was in control of the east and northeast. It launched a counteroffensive in late January, retaking parts of Omdurman, the twin city of Khartoum, and seeking to reverse the RSF’s progress in central Sudan, particularly in parts of El Gezira state, including the state capital, Wad Madani.

But this is far from being a national war only, given Sudan’s strategic position in relation to four regions – the Horn of Africa, North Africa, the Sahel and the Gulf. As well as causing suffering to millions of Sudanese, the war therefore has the potential to destabilize neighbouring countries such as Chad and South Sudan, create large new migration flows to Europe, and further militarize Sudan itself, owing to the arming and mobilization of ever greater numbers of civilians.

The military–business networks responsible for derailing the post-2019 democratic transition – first by carrying out a coup in October 2021 and then by plunging the country into war – continue to operate. The SAF and RSF own some of the largest companies in Sudan, and thus have access to huge financial flows with which to sustain their respective war efforts. SAF- and RSF-affiliated companies also have wide networks of international and regional relationships with state and non-state actors, competition among which has been fuelled in some degree by the SAF and RSF’s respective external engagements with them.

The SAF’s strongest regional relationship is historically with Egypt, most significantly through the Egyptian military. Many Sudanese army officers are trained in Egypt. The SAF has also had a military cooperation agreement with Egypt since 2021. SAF companies have close links with businesses affiliated to the Egyptian army, especially in the trading of agricultural commodities such as sesame. During the post-2023 war, the SAF has accrued foreign currency through the taxation of goods transiting Port Sudan. The SAF has sought support directly from foreign governments, including those of Egypt, Qatar and Türkiye, and has generated revenue by selling strategic commodities such as gold, livestock and agricultural goods to its allies.

From 2015 onwards, both the SAF and RSF received money from Saudi Arabia and the UAE in return for deploying Sudanese soldiers to the Yemen war. Subsequently, the RSF has strengthened its ties with the UAE, which has become a key backer of the RSF’s war efforts12 and an important conduit for the activities of the RSF’s business empire. UAE support has included hosting RSF front companies, providing the RSF with banking services, and being the main destination for Sudan’s gold exports (both legal and illicit).13 It is estimated that 50–80 per cent of Sudan’s gold is smuggled abroad,14 mainly through the UAE. In response, the SAF has increasingly sought to shift the destination of its own gold sales to Egypt (where Sudanese gold is exchanged for local currency and used to purchase commodities); this is to prevent that gold from going directly to the UAE, given the latter’s perceived support for the RSF. The outbreak of war in Sudan has also coincided with rising Egyptian demand for gold: Egyptians have been buying gold to preserve the value of their savings, in the face of a significantly weakened currency, and amid a worsening domestic economic crisis.15

Just as the SAF and RSF have shaped their external relationships to align with strategic goals, external actors themselves have continued to view Sudan as an arena in which to pursue regional influence. The UAE’s support for the RSF is offset by that of Qatar for the SAF, which has also sought support from Iran and Türkiye in providing drones. The UAE’s growing rift with Saudi Arabia has also been visible in those two Gulf states’ contrasting approaches to dealing with each side. Saudi Arabia’s attempts, alongside the US, to mediate between the warring parties at negotiations in Jeddah in 2023 were derailed partly because of UAE’s backing for the RSF (plus the fact that other countries supported the SAF). In pursuit of its interests in Sudan, the UAE has continued to leverage relationships with other regional allies, including with Libya’s Khalifa Haftar – the leader of the Libyan Arab Armed Forces (LAAF) – and the government of Chad.

At the same time, there has been a shift in regional dynamics, with Egypt and the UAE, who have so far backed opposite sides in the war, brokering talks between the deputy commanders of the SAF and the RSF in Bahrain in January 2024, which were attended by Bahraini, Saudi and US officials. Egypt – which is dealing with the impact of the war on its southern border – is exasperated with the SAF and the Islamist control over its decision-making. It has thus increasingly sought to keep both warring parties at equal distance and is engaging more with Sudanese civic stakeholders.16

These transnational relationships and cooperation arrangements not only connect Sudan to neighbouring countries and the broader region, including the Gulf and beyond, but also facilitate supply chains associated with the conflict. The warring parties are unlikely to stop fighting unless further steps are taken to target the financial flows and military supplies that are sustaining the war.

How contestation over Al Fashaga frames cross-border relations

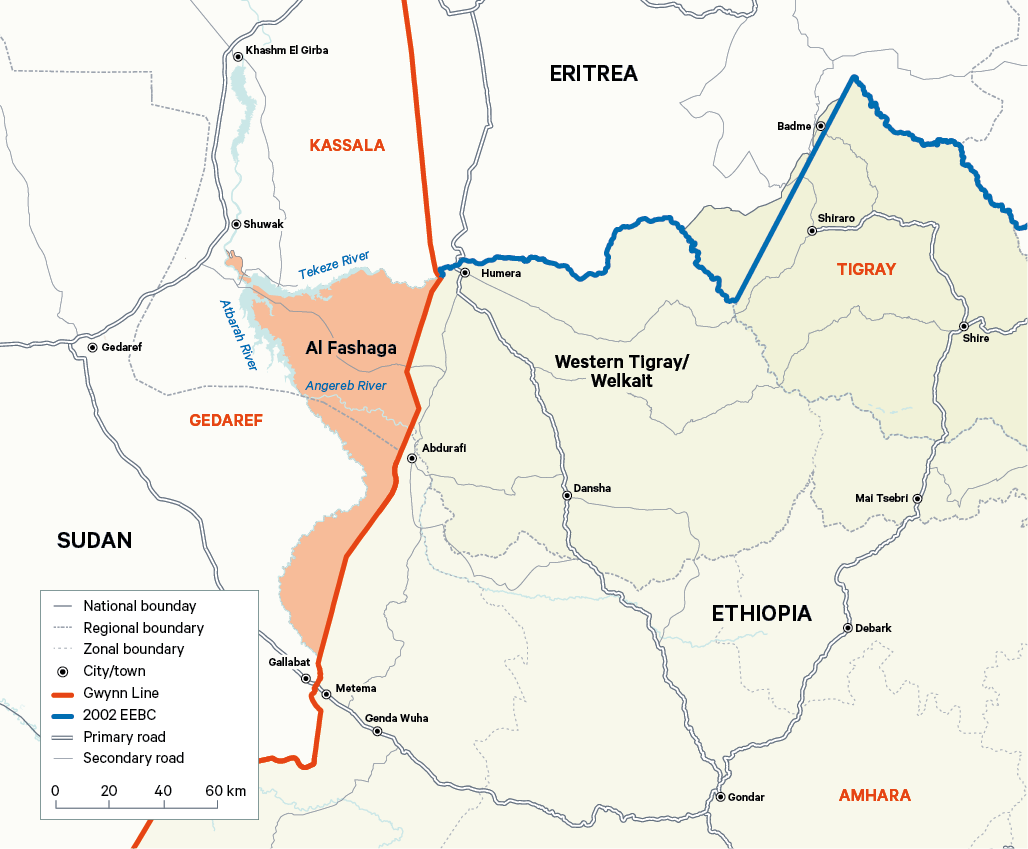

Ethiopian and Sudanese actors have historically competed for control of land and agricultural production in their borderland regions, with cycles of cooperation and conflict shaped by internal political dynamics and prevailing bilateral relations. Disagreement over the border as set out in the 1902 Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement, particularly in respect of the disputed Al Fashaga territory, has long shaped discord between Ethiopia and Sudan.17 Al Fashaga covers an estimated 250 square kilometres between the Atbarah River, on the Sudanese side of the border, and the Amhara and Tigray regions on the Ethiopian side. Al Fashaga contains 243,000 hectares (ha) of fertile agricultural land and produces a variety of crops, including export-grade sesame.

The 1902 agreement was followed by border delimitation work by Major Charles Gwynn, a British army officer of that period. In 1903, this delimitation awarded Al Fashaga to Sudan, but this territorial concession was never considered legitimate by the Ethiopian government. In 1972, an ‘exchange of notes’ between Ethiopia and an independent Sudan tried unsuccessfully to address and resolve the dispute. Several subsequent joint border committees continued this work, but without success.18 Sudan has resisted reopening the settlement proposed in the 1972 notes. Instead, it has suggested collaborative approaches that create the conditions for a soft border. Meanwhile, Ethiopia – and especially members of the political elite in Amhara regional state – continue to insist on an amendment and finalization of the border demarcation based on the 1972 exchange of notes.

Despite this official deadlock, the de facto situation has been one of local land-sharing between those living on either side of the national border. An informal cooperation formula was purportedly reached between Ethiopia and Sudan in 2007, whereby ‘Ethiopian and Sudanese citizens could both cultivate the land, with the two sides agreeing to undertake formal demarcation at an unspecified later date’.19 Although there is no documentation to verify this, Ethiopian farmers, largely from Amhara and Tigray, benefited from official trade routes and land-use arrangements developed during the era of cooperation between Meles Zenawi (Ethiopia’s prime minister from 1995 to 2012) and Omar al-Bashir (Sudan’s president from 1993 to 2019). This ‘allow[ed] both Ethiopian and Sudanese citizens to grow crops, put cattle to pasture and conduct trade in the area, reducing the urgency of border demarcation’.20

The claims and counterclaims on the area were among the factors that prompted the SAF to move into Al Fashaga, using force, following the start of the Ethiopian civil war in 2020.

However, the 2007 cooperation formula was not supported by a binding legal framework. Rather, it merely reflected the individual political interests of leaders who have since died or been removed from power. The demographics in Al Fashaga continued to change in the subsequent decade and a half, notably as a result of increased settlement by Ethiopian farmers and labourers. These changes contributed to tensions between Ethiopian and Sudanese farmers in Al Fashaga, fuelling recurring skirmishes and low-level conflict. The shift in the composition of the population was partly a result of the practice of Mofer Zemet – the occupation and farming of land deemed to be ‘unoccupied’ in border areas – by Ethiopian smallholders.21 Mofer Zemet and the search for free land for farming pushed Ethiopian farmers into Al Fashaga to ‘cultivate land they claim is part of Ethiopia, which, according to them, has been “unlawfully occupied” by the Sudanese’.22 Farmers engaged in Mofer Zemet are not usually permanent settlers, instead seasonally occupying areas of up to 5 ha in size.23

After 2015, the Ethiopian government, particularly the authorities in Amhara regional state, allowed the practice of Mofer Zemet to increase. This partly had to do with the weakening of central authority following Meles Zenawi’s death in 2012, as well as growing radical nationalism in Amhara that included stronger claims on the disputed territory. Mofer Zemet was seen by the Sudanese government as a strategy on the part of Ethiopia to control Al Fashaga by changing the demographics of the area. Settlements have generated hostility between local communities on either side of the border, particularly among Sudanese investors who claim to own land east of the Atbarah River.24

The claims and counterclaims on the area were among the factors that prompted the SAF to move into Al Fashaga, using force, following the start of the Ethiopian civil war in 2020. After the disastrous and widely unpopular military coup in Sudan in October 2021, the SAF further hardened its position on Al Fashaga and attempted to use the dispute to rally national support for its authority.

03 The economic value of sesame and its role as a transnational ‘conflict commodity’

Sesame is a valuable cash crop in Ethiopia and Sudan. Since 2020, the areas in which some of the best-quality sesame is cultivated have suffered conflict and instability. The crop has thus become a strategic commodity, the proceeds of which have been used to sustain conflict.

Sesame is the world’s oldest oilseed crop, originating from East Africa and Asia. It has historically been an important export crop for the predominantly agrarian economies of Sudan and Ethiopia. One of the key areas of sesame production (see Figure 1) is on either side of the border between the two countries, encompassing the eastern Sudanese states of Gedaref and Kassala, and the Amhara and Tigray regional states of northwestern Ethiopia.25 Sandwiched between them lies the disputed area of Al Fashaga.

The global sesame seed market was estimated to be worth $7.5 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow to $8.5 billion by 2028.26 The demand for sesame is largely due to its nutritious properties and its inclusion in a variety of foods.27 Ethiopia and Sudan have both ranked among the top 10 producers and exporters of the crop over the last decade.28 The type of white sesame produced in Gedaref and Humera, known as ‘white gold’ due to its colour, is in high demand. This is a function of both its quality and the relatively limited area in which it is produced. The crop is politically important, as the value chain has historically been controlled by local elites. Before the escalation of the dispute over Al Fashaga in December 2020, Ethiopian and Sudanese farmers had sold their sesame products in both countries, with the dynamics of this trade largely being determined by market conditions and structures, such as pricing and the profit margins sought by investors, traders and farmers.

The sesame industry in Ethiopia

The oilseed industry has been a major contributor to Ethiopia’s foreign exchange revenues in recent years, providing between $250 million and $500 million in export earnings per year over the last decade. The three main oilseed crops – sesame, soybean and niger seeds – contribute one-fifth of Ethiopia’s agricultural export profits,29 with the majority of this share coming from sesame. Oilseed farming of one kind or another provides a living for more than 3.7 million smallholders.30

Most of Ethiopia’s commercial sesame production has historically occurred in its northern and northwestern regions – notably in the Welkait, Metema and Humera woredas,31 close to the borders with Sudan and Eritrea.32 Until recently, Amhara regional state contributed 44 per cent of national sesame exports, while neighbouring Tigray contributed 31 per cent and Oromia 13 per cent. Sesame is also farmed on a smaller scale in several other regional states of Ethiopia.33

The sesame industry has been severely affected by conflict. Humera and Welkait were part of Western Tigray until they were annexed by Amhara forces in late 2020. Wollega in Western Oromia is also insecure, as the rebel Oromo Liberation Army has been conducting an insurgency in this area. The impact of conflict on production is indicated by figures showing that between 2019 and 2021, the total area in which sesame was harvested in Ethiopia declined from 375,120 ha to 270,000 ha.34 Additionally, actual exports of sesame more than halved between 2020 and 2022, from 247,501 metric tons to 107,719 metric tons.35 Yet, somewhat surprisingly, the country’s producers did not revise their export predictions as a result: in late 2022 (when the most recent forecasts were published), they still envisaged exporting 230,000 metric tons of sesame in 2023.36

The sesame industry in Sudan

Agricultural exports have become even more vital to Sudan’s economy since 2011, after the secession of South Sudan drastically reduced earnings from the petroleum sector. Sesame is one of Sudan’s main agricultural exports in the post-oil era: between 2011 and 2021, sesame accounted for nearly 30 per cent of such exports (inclusive of crops and livestock).37 Moreover, the area of sesame harvested in Sudan increased from 2.16 million ha in 2013 to over 4.15 million ha in 2022.38

Nearly 80 per cent of the area devoted to sesame seed farming is in the states of Gedaref, North Kordofan and Blue Nile, with the Darfuri states also contributing a significant share of production.39 All these regions were marginalized during more than 30 years of rule by the NCP. Darfur, Kordofan and Blue Nile have also been significantly affected by the current war. Mass violence and displacement in the five states of Darfur have decimated farming and subsistence livelihoods, while in North Kordofan supply lines and trading markets have been impacted by the RSF’s southern advance. The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N), led by Abdul Aziz al-Hilu, has sought to consolidate its control in South Kordofan, including over agricultural areas. The SPLM-N has also fought the SAF and allied forces in neighbouring Blue Nile state.

Nearly 80 per cent of the area devoted to sesame seed farming is in the states of Gedaref, North Kordofan and Blue Nile, with the Darfuri states also contributing a significant share of production.

Gedaref, still under the control of the national army (i.e. the SAF), has remained relatively stable in comparison. The state is considered to be part of Sudan’s ‘breadbasket’. It is well known for producing premium-quality sesame, contributing 30 per cent of Sudan’s production.40

Roughly one-half of national sesame production is semi-mechanized, while the other half comes from the traditional rain-fed sector.41 Production of high-grade white sesame tends to be semi-mechanized, taking place largely on commercial farms leased by well-connected traders and security officials. Such farms are often oriented towards profit-making rather than serving the long-term development and interests of local communities.42

Many of the workers on Gedaref’s sesame farms are migrants who have made arduous journeys to reach the area, and who then endure harsh working conditions. Large-scale farmers in Sudan source labour through both legal and illegal channels, and recruit tens of thousands of Ethiopian seasonal migrant workers for the planting and harvesting periods.43 Workers are poorly paid and vulnerable to abuse as ‘increased production involves further over-exploitation of both land and labour’.44 Labour exploitation is further fuelled by the persistence of historic power inequalities between the centre of the country and the geographic margins of Sudan. Members of the central elites – including some government officials, security officers and businesspeople – often demonstrate predatory approaches to land and resource use, and to dealings with people, in rural areas. This has resulted in recurring cycles of impoverishment and violence.

Sesame’s role as a transnational conflict good

Production of sesame and revenues from its trade have fluctuated in Ethiopia and Sudan in recent years, in part due to the tumultuous political and security contexts in both countries. Ethiopia’s revenues from sesame exports totalled $282 million in 2018. Subsequent revenues were uneven, but totalled $182 million in 2022 (the most recent year for which data are available).45 The value of Sudanese sesame exports earnings rose from $576 million in 2018 to a peak of $789 million in 2020 before falling to $488 million in 2022.46 Despite this, sesame remains one of Sudan’s most valuable export commodities after gold, roughly on a par with livestock.47

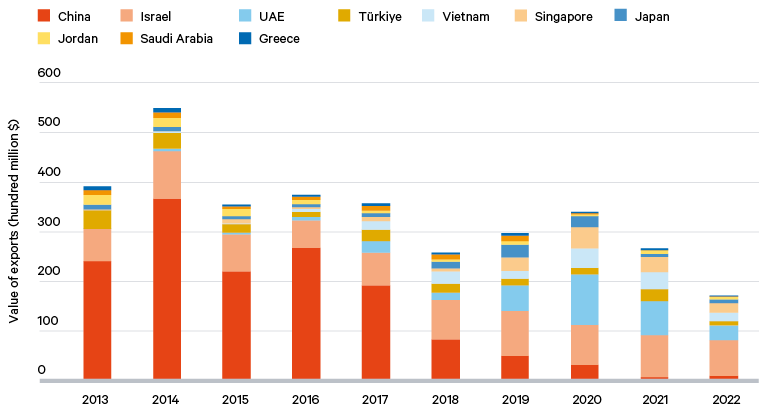

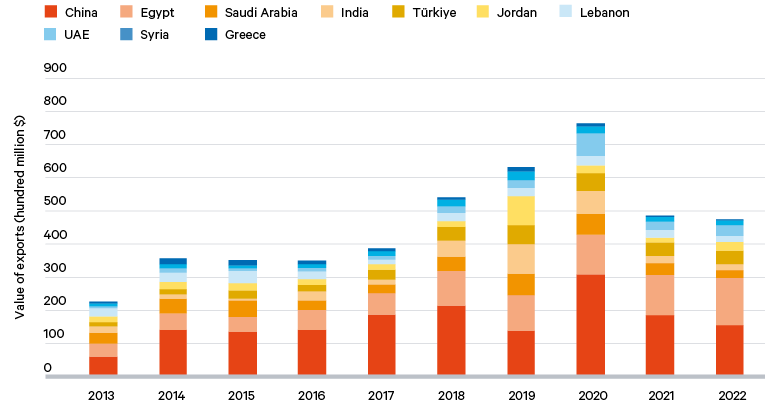

Figures 2 and 3 respectively illustrate Ethiopia and Sudan’s top sesame seed export markets over the past decade.

These data suggest a correlation between transnational relations and trade. Some of the largest importers of Ethiopian and Sudanese sesame are also among the countries that have played an outsized role in shaping the region’s tumultuous political shifts in recent years.

For Ethiopia, the most important sesame export markets have included Israel, the UAE and, until recently, China. Of these partners, the UAE is an important supporter of the Ethiopian federal government, having invested to aid the struggling Ethiopian economy as well as having delivered critical military supplies to help turn the tide of the Tigray war.50

Of Sudan’s main sesame export markets, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE warrant particular attention in terms of the intersection between their trade relations and diplomatic agendas. These countries are leading regional stakeholders with direct interests in shaping the outcome of the war in Sudan. Egypt maintains strong relations with the SAF and has close economic links with Sudan more widely, particularly in agriculture. The Saudis, meanwhile, have been closely involved in mediation between the warring parties. The UAE – a key backer of the RSF – was also a significant importer of Sudanese sesame before the conflict started. Saudi and Emirati interests in Ethiopia and Sudan are partly shaped by their aspirations to boost their own food security.

Türkiye is another important destination for Sudanese sesame. Both Ethiopia’s government and the SAF have sought to procure Turkish-made drones during their internal conflicts,51 with the Sudanese military regime also seeking economic support from its regional allies through the sale of strategic commodities such as sesame, gold and livestock.

The data on Ethiopia and Sudan’s sesame exports highlights the link between diplomatic alliances and transnational trade, which also converge with conflict dynamics. There is a credible argument to be made that sesame, normally an agricultural crop without obvious military relevance, has become a securitized economic resource or ‘conflict commodity’. This reflects the fact that its production and trade have been captured and controlled by armed groups, and that the proceeds from such trade are used to fuel conflict by national or subnational actors. Thus, the definition of what constitutes a conflict good needs to be expanded beyond the products or commodities typically associated with armed violence – such as illicit minerals, weapons or drugs.52 The sesame industry not only connects Ethiopia and Sudan to other regional powers – notably, as mentioned, in the Middle East – but also fuels a war economy that sustains conflict in both countries. Moreover, given the large financial interests at stake, the new dynamics of such an economy can make the resolution of conflict more difficult.

04 The role of sesame in driving rivalries in Ethiopia

The sesame-growing region of Western Tigray/Welkait was the focus of a fierce struggle between Amhara and Tigrayan forces during the 2020–22 civil war. Amhara currently controls the contested territories, but the sesame sector has been left decentralized and fragmented.

Violent conflict on the Ethiopia–Sudan border, and internally in both countries, is having ‘redistributive’ and transformative effects. It is creating new power-holders, and new political and economic winners and losers. The examples presented so far in this research paper illustrate how important economic resources, or conflict goods, such as sesame can be used to fuel conflict when captured by certain groups – including national armed forces, but also rebel groups and economic elites linked to such groups. Ethiopian dynamics have been predominantly driven by internal contestations. However, the latter has still been consequential for Ethiopia’s cross-border relations with Sudan.

The boundaries between most of Ethiopia’s 12 national regional states are the subject of disputes. These disputes often degenerate into violent conflict. The most contentious dispute today is over territory spanning the Amhara and Tigray regional states. Since the civil war began in 2020, forces from Amhara have captured vast expanses of land in western and southern Tigray.53 Amhara claims that these territories – which include key sesame-producing areas – were seized from it by Tigray 30 years ago, after the ethnic coalition dominated by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) came to power. This earlier assimilation of territories into Tigray, which Amhara has sought to reverse, allegedly occurred without the consent of local people and has been a source of hostility between Amhara and Tigrayan nationalists since the early 1990s. However, since late 2020 the contested territories have been under Amhara control, although both sides continue to claim them.54

Competition over the sesame sector and for control of land has reinforced ethnic and political fragmentation. Before the war, the sesame and wider agricultural sector in Western Tigray/Welkait had been dominated by Tigrayan business interests, through the TPLF’s business conglomerate, the Endowment Fund for the Rehabilitation of Tigray (EFFORT), and its subsidiary, Hiwot Agricultural Mechanization PLC.55 The transportation and export of sesame were facilitated by Guna Trading and Trans Ethiopia, both also belonging to EFFORT.

Amhara forces’ annexation of the area in late 2020 resulted in contestation for the control of sesame production and export. As a result, the previously integrated sesame sector has become decentralized and fragmented, and the role of the formal Ethiopia Commodity Exchange (ECX) mechanism has been severely diminished. The precise role of the Amhara state government in the sesame sector is unclear. There are suggestions that Nigat (a parastatal business previously called Tiret Corporation)56 has taken over the role previously played by Hiwot.57 Nigat owns 19 companies and controls much of the Amhara regional state’s economy, including agricultural assets.58 Following the change of government in 2018, Nigat was made the public property of the Amhara people, and legally accountable to the Amhara Regional Council.59

The emerging intersection of Amhara nationalism with business and security interests has meant that profits from the sector have served to reinforce de facto Amhara control over the disputed Western Tigray/Welkait region. Thousands of displaced Tigrayan inhabitants have been replaced by ethnic Amharas (many of them from Gonder),60 who have been enticed to settle there by the Amhara state government’s offer of grants and land. The interim zonal administration and joint Amhara security forces have facilitated this process. This shift has further driven competition for control of the sesame sector – with such competition now involving local authorities, businesspeople, security officers, individual farmers, investors and smugglers, as well as non-state armed groups such as the Amhara nationalist Fano militia forces, Qemant insurgents, armed bandits and Eritrean forces.61 Private businesspeople with strong state connections and links to the Amhara military62 are also an important part of the sesame production and export chain.

Much of the sesame farmed in Welkait and Humera is now exported through channels outside of the formal Ethiopia Commodity Exchange mechanism, which has led to the sector becoming increasingly securitized and unregulated.

In 2021, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed inaugurated two major edible-oil refineries in Amhara regional state, including the Fibela Industrial Complex – Ethiopia’s largest edible-oil refinery. When fully operational, the refinery is projected to supply more than 60 per cent of the country’s edible-oil demand.63 The facility is owned by one of the wealthiest businesspeople in Ethiopia, Belayneh Kindie, whose Belayneh Kindie Group (BKG) is the country’s largest exporter of sesame seeds. In May, another oil refinery was established worth 5 billion birr (equivalent to c. $88 million at the current exchange rate).64 Having the capacity to process 1.3 million litres of edible oil daily, the plant is located in East Gojjam Zone and is owned by another prominent Amhara businessman. The factory, which has since stopped production, has also been implicated in providing support for the Amhara nationalist Fano militias which have been leading regional protests during the last three years.65

Much of the sesame farmed in Welkait and Humera is now exported through channels outside of the formal ECX mechanism,66 which has led to the sector becoming increasingly securitized and unregulated. Political instability in Amhara state has further exacerbated this trend towards informal and/or contraband trade.67 The formal sector (including producers, buyers and exporters) is heavily controlled by delala (‘brokers’), who also regulate the sale of sesame outside formal channels via a complex transnational supply chain. The delala often lend money to local farmers if the farmers cannot afford to pay daily labourers or buy agricultural inputs. In this way, the brokers maintain an advantage in the market, as farmers caught up in such arrangements are then obliged to sell their crops to the brokers that have provided loans.68

Informal trade takes place across multiple borders – administrative, legal, social, community – and occurs despite ad hoc infrastructure and inconvenient border impediments (securitization, taxation, corruption, etc.). Smuggling is driven in part by the fact that official state policies on trade are often impractical and restrictive.69 It is also often a necessity due to the lack of alternative livelihood options, and this way of life has emerged as part of the accepted cultural fabric of borderland communities.70

Subregional contestation

As well as stoking regional rivalry between Amhara and Tigray, attempts to control the sesame sector have generated tensions between subregional Amhara elites (from Gojjam and Gonder) and indigenous Welkaites. The latter have a mixed cultural background, reflecting their links to both Amhara and Tigray. Previously marginalized under TPLF rule, the Welkaites have since sought to reclaim land and influence by aligning themselves with powerful Amhara elites.71 But this hope has not been fully realized. From 2021 until early 2024, the local Welkait administration was reliant on financial assistance and in-kind support from the Amhara state authorities, rather than receiving regular funding from the federal budget,72 while Welkait officials have been strengthening their ties with members of the Amhara security and business elites, as well as with the Eritrean regime.73

The area encompassing the annexed Western Tigray/Welkait region is currently administered as the ‘interim Welkait-T(s)egede-Setit-Humera zone’,74 led by a mix of the Amhara Prosperity Party (PP) and representatives of the Welkait Tegede Amhara Identity Restoration Committee.75 This local administration has sought to push the Welkait issue to centre stage in Amhara nationalism and national politics, and to promote Welkait leaders as protectors of Amhara identity. Some members of the administration have been implicated in ethnic cleansing and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Tigrayans from the area during the civil war. 76

With little federal-level financial support, the interim Welkait administration views the sesame sector and agricultural land as crucial for revenue generation. In April 2021, the Amhara regional government issued a directive encouraging investment in the area to cultivate the ‘liberated’ land, and provided one-year leases to capable investors. The initiative was subsequently extended until the end of the 2022 harvest season.77 The idea was that successful investors would continue farming sesame and other crops in the coming years, and that mutually beneficial working relationships would thereby develop between investors, the local administration and the security apparatus.

The Amhara Bureau of Rural Land Administration and Use is nominally in charge of overseeing land lease agreements covering areas larger than 10 ha.78 But field research conducted for this paper suggests instead that the regional state government in Bahir Dar has allowed the interim Welkait administration to apportion land in the zone without interference.79 As a result, Welkait has effectively had carte blanche to lease land for agricultural investment, likely to the benefit of those with close personal and business ties to the administration’s leadership. Supporters and enablers of the local administration have been granted farmland, including land likely to have been seized from Tigrayans.80 The Welkait authorities have discretion to exclude smaller farmers or investors from these land lease transactions. Those affected are likely to include locals or farmers displaced from Al Fashaga due to Sudan’s annexation of the territory. This situation has the potential to cause further unrest and conflict in the interim Welkait-T(s)egede-Setit-Humera zone.81

Land grabs in Western Tigray/Welkait

Given the shifts in control of the sesame sector, the expansion and control of fertile agricultural lands used for sesame production has become an issue of contention among local farmers in Western Tigray/Welkait. Field research for this paper indicates that parts of the lowland agricultural farms around Humera have been occupied (sometimes forcibly) by members of emerging Amhara economic elites.82 These actors often maintain connections with government officials at either the local, regional or federal level, as well as with members of the diaspora community, and are sometimes implicitly backed by Amhara militias. These new economic elites have taken over lands that used to be controlled by TPLF-affiliated companies, investors and politicians. The legality of such appropriations, especially since they have been driven by wartime displacement, is highly contested.

There are also cases of local Amhara farmers who possess legal documents confirming their land rights but who have nonetheless been forcibly evicted by powerful individuals. Since the existing interim Welkait administration lacks formally recognized government structures, these disenfranchised members of the local community are unable to seek justice through the courts, or appeal through any other government body. Since ‘liberation’ from TPLF rule, some local Amharas see themselves as victims of the current interim administration. Emerging patterns of land control and access to agricultural assets (including, but not only, in the sesame sector) often fail to take community interests into consideration. Some farmers are still being denied what they claim are their political and economic rights, despite the removal of the TPLF administration from the zone.

The influence of national politics

Amhara’s ability to retain control over Western Tigray/Welkait in the long term remains uncertain, due to shifting political alliances at the national level between Amhara, Tigrayan and Oromo elite groups. The Amhara regional leadership – its middle and low-level officials in particular – is increasingly suspicious of the federal government, with concerns driven by the sense that the implementation of a peace deal with Tigray – following the Pretoria Agreement – has been achieved at the expense of the Amhara region. The Amhara regional leadership has found itself in a difficult position in terms of ‘selling’ the idea of a peaceful resolution of the conflict to its constituents, given that the Pretoria Agreement calls for disputes over ‘contested areas’ to be resolved constitutionally. This has stoked Amhara fears that proposals for the establishment of a new interim administration will lead to the area’s return to Tigrayan control, raising the prospect of an influx of thousands of largely ethnic Tigrayan IDPs.83 Their arrival, in the eyes of Amhara’s leadership, would jeopardize Amhara’s consolidation of power in Western Tigray/Welkait, while depriving Amhara elites of access to critical economic resources such as sesame – the profits from which have partly been used to reinforce territorial claims and create new facts on the ground in Amhara’s favour.

This dynamic has contributed to mounting tensions and conflict between, on one side, the allied federal government and Amhara regional state government and, on the other, non-state Amhara Fano militia forces and Amhara nationalists. The Fano forces lack consolidated leadership and operate in a fragmented manner, but they were still able to take control of some zones and administrations in the region, leading to the imposition of a state of emergency on 4 August 2023 and the administration of the region via ‘command post’.84 Insecurity in cities such as Gonder has continued into 2024.85 However, Colonel Demeke Zewdu, the most prominent official in Welkait, has recently sought to distance his interim administration from the ongoing Fano insurgency elsewhere in the Amhara regional state, in part due to their reliance on federal forces and government support to continue controlling the zone.86 Moreover, some members of the Amhara elite believe that the issue of Western Tigray/Welkait has been holding the Amhara nationalist cause hostage, despite it being a rallying point for their cause since 2016.87 These developments threaten the sustainability of peace in northern Ethiopia, particularly if there were to be renewed hostilities between Amhara and Tigrayan forces over control of Western Tigray/Welkait.

Impacts on transnational relations with Sudan and Eritrea

The consolidation of control over Western Tigray/Welkait by nationalist Amhara elites has implications for Ethiopia’s cross-border relationships with Sudan and Eritrea. Some Amharas see the control of this land as partial consolation for having lost the fertile farmlands of Al Fashaga. As the war in Sudan deepens, so does the possible threat to the SAF’s authority in eastern Sudan. Such a scenario might elevate nationalist Amhara voices, who advocate that Ethiopia should retake Al Fashaga by force.

Despite Ethiopia’s stated neutral position in respect of the war in Sudan, escalation would be difficult for the Ethiopian federal government to control.

Depending on how the current instability in the Amhara region evolves, and how the unresolved future of Amhara-controlled Western Tigray/Welkait is addressed, this could lead to renewed cross-border tensions between actors in Ethiopia and Sudan. Certainly, such tensions would become more likely if the Ethiopian federal government moves forward with plans for a referendum on the status of contested areas, or with a plan to reshape the interim regional administration to make it more neutral ahead of a referendum.

Any renewal of raids by Amhara forces into Al Fashaga would inflame tensions between Ethiopia and Sudan. Despite Ethiopia’s stated neutral position in respect of the war in Sudan, escalation would be difficult for the Ethiopian federal government to control. And – although a distracted and stretched SAF would be unlikely to have the resources to retaliate – the SAF could seize on such incidents to further the arming and mobilization of civilians in eastern Sudan in an attempt to increase popular resistance on its behalf, including by Islamist brigades such as the Popular Defence Forces and Popular Security, as well as other armed movements.

Eritrea also remains an active and interested party in this tri-border region. Its strengthening of ties with local Amhara elites – the field research for this paper suggests that a trading route between Ethiopia and Eritrea now exists for the first time in over 25 years via Western Tigray/Welkait – has contributed to growing tensions between Eritrea and Ethiopia’s federal government. There are indications that shipments of sesame and other goods from Amhara-controlled Western Tigray/Welkait to Eritrea have been used as payment in kind for Eritrean forces’ protection, training and support of Amhara Fano militias.88 Dependence on Eritrean military support has enabled Eritrean traders to impose financial terms vastly in their favour.89 This mostly one-way cross-border smuggling remains outside the control of the Ethiopian federal government, and provides little benefit for local people in Western Tigray/Welkait – except for those engaged in smuggling.

Sudan, too, has been anxious about Ethiopia’s closeness with Eritrea, particularly given Eritrean involvement in eastern Sudan (including through local tribes spanning the borders, such as the Beni Amer, Beja and Rashaida groups) and the alliance between Eritrea and elements in Amhara. However, since the establishment by Sudan’s military regime of a de facto administrative capital in Port Sudan in the east of the country in August 2023, the SAF has sought to strengthen its alliances with Eritrea to counter such issues.90 These developments suggest that the future of Al Fashaga and the contested tri-border region between Ethiopia, Sudan and Eritrea remains uncertain. Equally uncertain is what these interlinked dynamics might mean for prospects for regional peace.

05 The role of sesame in Sudan’s war economy

Sudan’s sesame industry has become increasingly securitized in recent years. The SAF has reinforced its control of the disputed Al Fashaga region. At the same time, army-aligned companies have sought to exploit commercial opportunities, dislodging local businesses as well as Ethiopian investors and farmers.

The outbreak of war in Tigray in late 2020 enabled the SAF to take control of a large swathe of territory in Al Fashaga.91 For Sudan, the capture of Al Fashaga was connected to the SAF’s concerns over national territorial sovereignty and a desire to control economic resources. The SAF’s action, which began in December 2020, ended the uneasy truce under which Ethiopian farmers cultivated the land under nominal Sudanese administration. It also led to the SAF consolidating its agricultural interests in Al Fashaga, including by taking over the sesame sector. Thousands of predominantly Amhara farmers and some investors, many with long-standing ties to the local economy, were evicted and forcibly displaced to Ethiopia.92

From economic interdependence to securitization

Gedaref and Kassala – the Sudanese states overlapping Al Fashaga – have a long history of immigration and ethnic diversity. Their populations include significant numbers of people who originally come from other parts of Sudan – as well as from neighbouring countries such as Ethiopia – attracted by the area’s rich natural resources and economic potential in agriculture and minerals. Several groups, mainly from western Sudan (Darfur and Kordofan), had settled in the area when the Mahdi revolution expanded in the late 1890s. Beja tribes such as the Hadandawa are also prominent in the area, along with groups such as the Beni Amer and Rashaida, who inhabit territory stretching across the Sudanese border into Eritrea.

Three main sets of stakeholders have historically played leading roles in the social, political, economic and security spheres of Gedaref and Kassala states. The first consists of the military and, to a lesser degree, other security forces that make up each state’s security committee.93 The second set of actors consists of businesspeople and farmers who lead the region’s core economic activities of agriculture (including sesame production) and livestock farming. The third set are the ‘Nazara’: native administrations that represent the traditional tribal system. The Nazara often help ensure social cohesion in these multi-ethnic states,94 and play an important role in managing resources and overseeing and arbitrating land ownership issues.

In Gedaref state, around a dozen members of the Sudanese business elite own large areas of agricultural land (over 20,000 feddan each,95 or 8,400 ha). Their holdings include sesame farms, livestock farms or pastures, and agro-processing factories.96 There is also a small number of investors with much larger holdings (hundreds of thousands of feddan). Given the predominance of farming in the state, major investors have important roles in local government and the native administrations. These dual roles are significant, enabling members of the business elite both to take the lead on cross-border trade and to have a say in managing relations with Ethiopia – historically a vital market for Gedaref-produced goods, as well as a source of seasonal workers.97

Due to the inaccessibility of the sesame-producing areas in Al Fashaga (which is physically seperated from Gedaref state by the Atbarah river), Sudanese landowners have often gone into partnership with Ethiopian farmers, or have leased lands to them for long periods for use in traditional rain-fed agriculture. Such arrangements have often been conducted without government intervention. Farmers in Gedaref have also had to deal with local labour shortages caused in part by outward migration, increasing living costs, and a preference among many workers for employment in more lucrative sectors such as mining. This has prompted some agricultural employers to become more reliant on migrant Ethiopian labourers, typically recruited during the planting and harvesting seasons (which run from late May to July, and from October to April, respectively).98

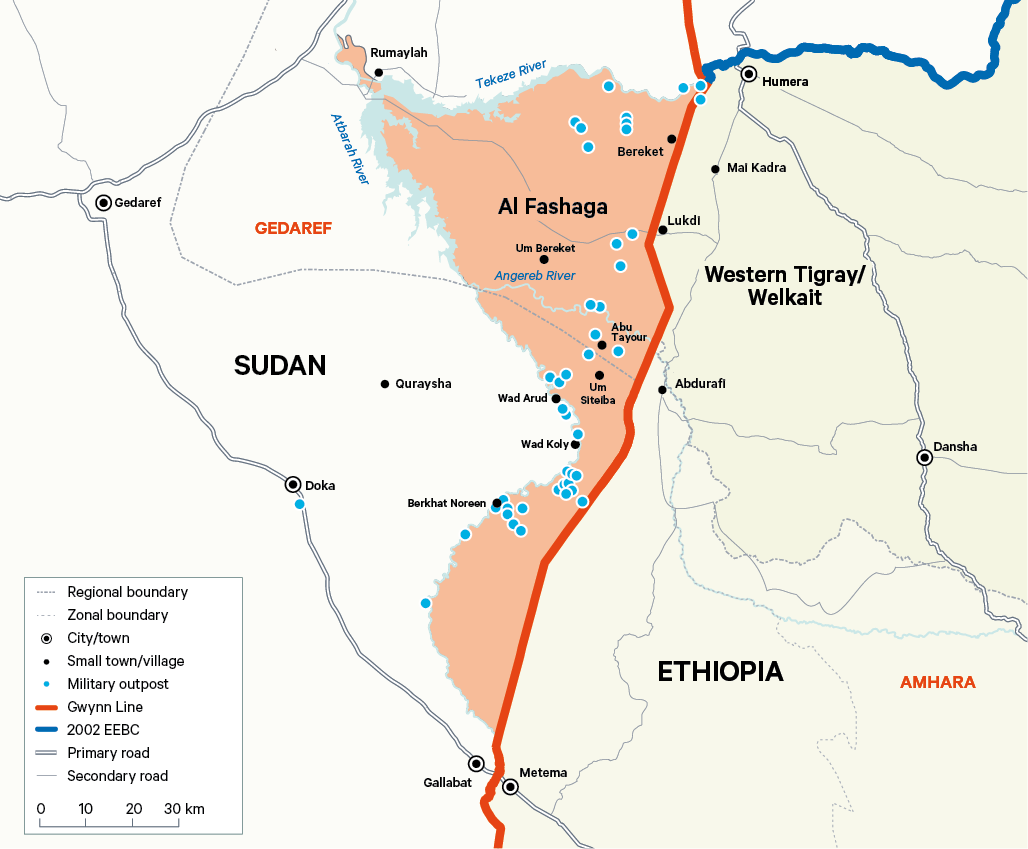

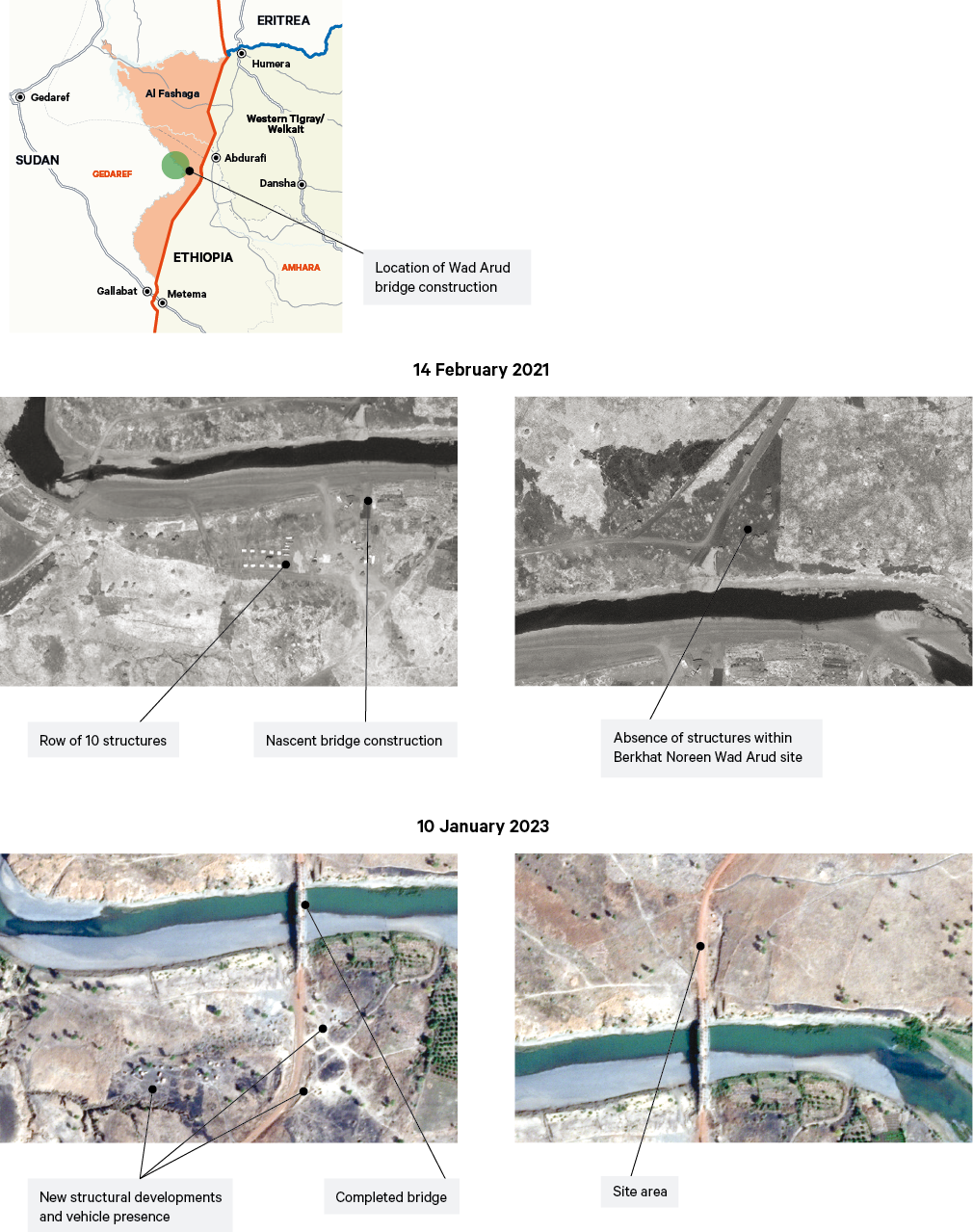

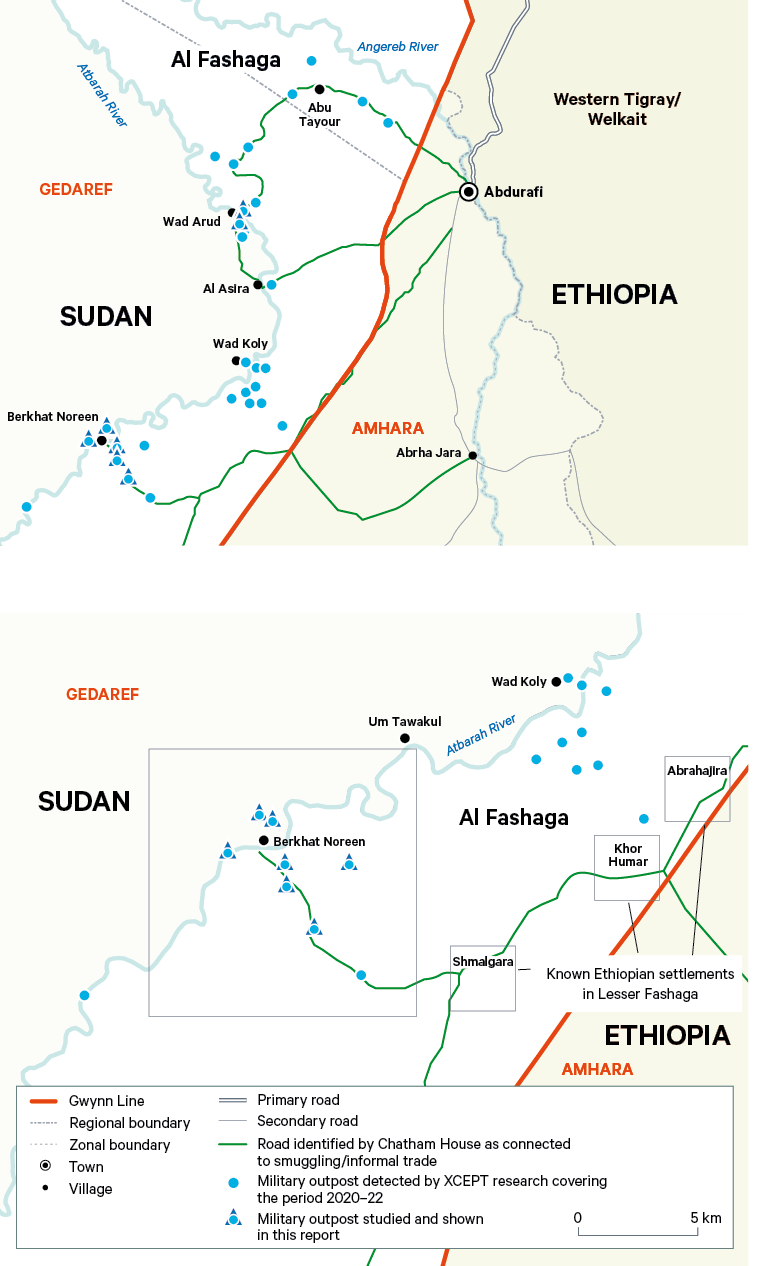

Over the past three years, military force has been central to the governance of these borderlands. Since late 2020, the SAF has built new and reinforced outposts (see Figure 4), and now controls over 90 per cent of the disputed areas in the Al Fashaga triangle. A key consequence is that the land on which sesame is grown and traded has become increasingly securitized. The SAF has reinforced its territorial control through significant infrastructural developments, including the construction of four bridges across the Atbarah River.

Two of the bridges, at Wad Koly and Wad Arud, are permanent. The other two, at Sondos and Berkhat Noreen, are temporary. Satellite imagery (Figure 5) shows the construction of the Wad Arud bridge by the SAF between 2021 and 2023. This has provided Sudan with a permanent physical link between Al Fashaga and the rest of Gedaref state. It has facilitated the movement of people and goods to lands between the river and the border, an area previously occupied by Ethiopian farmers.

The construction of the four bridges is significant because the Atbarah River had previously formed a natural obstacle that prevented Sudanese farmers from accessing farmlands on the eastern side of the river. In contrast, Ethiopian farmers could reach this area with relative ease. Figure 6 (see p. 36) illustrates the consolidation of Sudanese control over Lesser Al Fashaga through the progressive establishment of military outposts between late 2020 and 2022. This is visible at Berkhat Noreen, where between December 2020 and March 2021 the SAF transformed several agricultural and unpurposed areas of land into military bases as its forces progressed across the river and consolidated their presence further into Al Fashaga. Typically, these outposts included the removal of existing tukul used for agricultural livelihoods,99 and the construction of defilades, artillery berms and trench fighting positions to protect armoured fighting vehicles and other structures including tents.100

The SAF expansion was also intended to curtail Ethiopian agricultural activity in Al Fashaga. Figure 6 clearly illustrates the alignment of SAF military outposts with existing informal trade or smuggling routes, some of which had been built by Ethiopian farmers and smugglers over several years to facilitate the movement of sesame, other agricultural goods, contraband and people from Al Fashaga into Ethiopia. The SAF’s advance into Al Fashaga sought specifically to intersect with and disrupt these trading routes, and thus to take control of the agricultural sector in the area and cut off Ethiopian settlements, including those identified in Lesser Fashaga (such as Shmalagara, Khor Humar and Abrahajira).

The impact of the military takeover of Al Fashaga

The SAF’s incursion into Al Fashaga and subsequent securitization of the area have affected many of those involved in the local sesame sector – from businesspeople to farmers and labourers. The military takeover has also disrupted relationships between Sudanese and Ethiopians living on either side of the border. Some local Sudanese businesspeople have not been compensated for the loss of their lands to their own military, with these lands instead being offered to investors more closely aligned with the SAF. The military has also brought in seasonal labourers and farmers from outside Gedaref to farm the captured land. As a result, local businesspeople have lost productive relationships with Ethiopian farmers, investors and labourers, who had previously farmed this region under mutually beneficial arrangements. Bereket, in Greater Al Fashaga, is one such area. It became a hub for Ethiopian sesame farming from 2012 to 2020. Permanent and semi-permanent roads were built from Al Fashaga into Ethiopia to facilitate the export of sesame and other agricultural products, as well as the movement of migrants and workers into Sudan. However, once the SAF took control of this area in 2021, Ethiopian residents were removed from Bereket and the previous arrangement ended.

The military takeover has disrupted relationships between Sudanese and Ethiopians living on either side of the border.

Security-linked companies and investors have moved into the sesame sector, with the presumed goal of rerouting control of the sector away from Ethiopian markets. Some of these companies are connected to Sudan’s Defense Industries Systems (DIS), a large SAF-owned conglomerate that generates financing for the army through multiple commercial ventures.101 DIS is headed by Mirghani Idris Suleiman and chaired by Burhan.102 DIS’s annual revenues were estimated at 110 billion Sudanese pounds (equivalent to $2 billion at the prevailing exchange rate) in May 2020.103 Zadna, one of DIS’s largest subsidiaries, operates in the agricultural and livestock sector. It was set up in 1997 under the control of the National Islamic Front, the Islamist political party led by Hassan al-Turabi, which at the time was allied in power with the NCP. Such parastatals were part of a complex economic network established under the Bashir government to empower members of the NCP Islamist-military regime, known as the al-Ingaz (‘Salvation’).104

In recent years, Zadna has been under the control of the SAF’s Special Fund for the Social Security of the Armed Forces (SFSSAF). According to the US Treasury Department, citing public media reporting, this arrangement has the express purpose of shielding Zadna from civilian oversight.105 During the transitional period from 2019 until the military coup in 2021, DIS eluded the control of the civilian authorities, which received no taxes, duties or customs fees from the activities of army companies, even those in civilian sectors such as agriculture.106 The US, the UK and the EU have all sanctioned DIS and Zadna for engaging in activities that sustain the war and destabilize Sudan.107

Despite these developments, there remains some domestic support for the military’s actions, particularly among certain local Sudanese investors hostile towards their Ethiopian counterparts on account of the latter’s exploitation of farmland in Al Fashaga. ‘The presence of Ethiopian farms in Al Fashaga, next to Sudanese farms, has made it easy to smuggle Sudanese crops into Ethiopia with a higher price and little to no taxes,’ said one businessman. ‘I lost some of my land 20 years ago and I am still waiting for a resolution,’ he added, ‘and until now I have lost all of my remaining land east of the river.’108

The farming of sesame crops in Al Fashaga, and their smuggling into Ethiopia, has also been connected with armed Amhara militias, known as shifta (‘bandits’). These groups have perpetrated cross-border raids to steal crops and livestock, particularly during harvest periods, and have also provided armed security for Ethiopian farms in Al Fashaga.109 In recent years, incursions into Al Fashaga by the shifta have been influenced by a growing and politicized nationalism within the Amhara ethnic group. This nationalism has included more forceful claims over territory in Al Fashaga. Cross-border attacks increased during the Tigray war, peaking in mid-2022, when the SAF accused the ENDF of executing seven captured Sudanese soldiers and a civilian following cross-border clashes.110 However, the Ethiopian government blamed Amhara shifta.111 While armed Amhara incursions were not directly backed by the Ethiopian federal government, it has often quietly acquiesced to such attacks. This assent partly seems to have stemmed from the Ethiopian leadership’s anger over the SAF takeover of Al Fashaga, its concerns at the time over Sudanese support for the TPLF, and the implicit threat of Tigrayan militias in eastern Sudan. A further motivation seems to have been the importance of maintaining the favour of Amhara special forces and militias, and of maintaining the Amhara militias’ alliance with the ENDF, during the Tigray war.112

The full extent to which the SAF and companies working with it have been able to control and redirect sesame trade flows remains unclear. Since the outbreak of the civil war in Sudan in April 2023, Al Fashaga has remained under SAF control, with eastern Sudan seeing limited fighting to date. The indications are that the sesame and sorghum harvests in 2023 were largely unaffected by the war. However, the emerging war economy will no doubt have a substantial impact on profitability for those operating in the sector. The costs of the war are high, reflecting impacts on critical processing infrastructure, the looting of key inputs, rising transportation costs (in part due to additional checkpoints), and the imposition of additional export and import tariffs through Port Sudan.113

Continued war is likely to have a negative impact on the coming planting period for sesame in Al Fashaga, which runs from late May to mid-July during the rainy season. This is due to likely restrictions on the availability of agricultural inputs such as seeds and fertilizers, as well as the limited availability and increased costs of fuel. The SAF is likely to prioritize production of sesame, given that the crop has become a strategic commodity and a vital source of foreign currency (when other sources are limited). The SAF can therefore use income from sesame trade to sustain its war effort, and to maintain support from regional allies where the product is sold.

However, if the RSF, having already taken control both of Wad Madani in neighbouring El Gezira state and of key transport routes, manages to push into eastern Sudan, this is likely to have implications for the sesame trade. In particular, the transport of sesame to Port Sudan and the export of sesame from the port are likely to be restricted. This scenario would result in further negative outcomes for local business owners and their workers in Gedaref and Al Fashaga.

06 Conclusion and recommendations

Policymakers considering how to shape effective conflict responses in the Ethiopian and Sudanese borderlands need to expand their notions of the types of commodities that contribute to violent outcomes. They should also ensure that holistic interventions target cross-border, as well as domestically driven, causes of conflict.

The sesame-producing regions of Ethiopia and Sudan sit at the centre of a set of interrelated conflicts. Cross-border tensions over Al Fashaga have soured recent bilateral relations. Both countries are also facing acute internal crises, complicated by external influences. All of these destabilizing factors are playing out against a backdrop of entrenched intra-regional rivalries and local grievances.

Focusing on the sesame industry, this paper has argued that – in the context of current conflict and political volatility – superficially unremarkable trading arrangements in this commodity do more than merely connect Ethiopia and Sudan to each other and the broader region. Economic processes associated with cash crops can also drive trade in ‘conflict commodities’. This trade not only fuels and sustains conflict but is enabled by it. The implications for conflict risk and mitigation go far beyond the immediate economic impact on national balance sheets or local livelihoods.

Given the conflicts and internal political challenges both countries are facing, the unresolved dispute over Al Fashaga remains a key flashpoint. If political and economic conditions in Al Fashaga remain unaddressed, they could escalate swiftly beyond this specific border area and into Sudan and Ethiopia’s wider political economies. Any broader escalation, however accidental, could have devastating consequences for both countries and more widely across the Horn of Africa.

Significant political uncertainties continue to affect conditions in Al Fashaga. In Sudan more broadly, uncertainty remains over the evolution of the country’s civil war, and over the development of the war economy and its impact on eastern Sudan. Meanwhile, in Ethiopia political tensions continue to create uncertainty over the future trajectory of the deepening conflict in the Amhara region between the Fano militia forces and the Ethiopian federal government, as well as over the role of Eritrea and the sustainability of any resolution to the Tigray conflict (such resolution remains elusive).

These unpredictable conditions make policy prescriptions incredibly difficult to pin down. The following recommendations are aimed at helping sharpen the focus of policymakers – both domestic and international – who hope to propose and shape effective interventions. As such, some of the recommendations target policymakers in Ethiopia and Sudan, while others are intended primarily for regional and international actors seeking to support peaceful political transitions in both countries.

Local conflict and cross-border considerations

Policymakers and development partners need to: