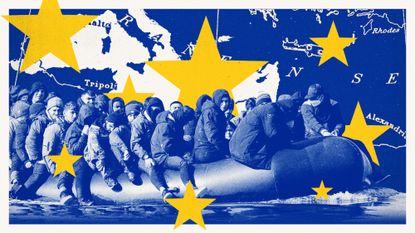

Following a lull in 2022, the EU is facing a surge in migrants crossing the Mediterranean

(Image credit: Illustration by Stephen Kelly / Shutterstock / Getty Images)

The European Union is trying to counter a surge in support for far-right populists by signing a deal with Egypt aimed at tackling illegal migrant crossings in the Mediterranean.

The migration and aid package will see the EU give €5 billion in cheap loans, €1.8 billion of investments and €600 million in grants, including €200 million to fight migration directly, to Egypt over the next four years.

Agreed by a delegation led by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and Italy's Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, the package "fits into a series of similar deals that Brussels has signed with countries on its periphery", said Politico, "as European leaders aim to curb irregular migration to the bloc ahead of the pan-EU election coming up in June".

What did the commentators say?

The strategy adopted by the EU differs from that of the UK government by prioritising economic support for countries on the front line of the migration crisis.

With annual inflation running at 30%, Egypt is struggling to cope with the nine million migrants that it currently hosts. These include four million Sudanese, one-and-a-half million Syrians and an increasing number of Palestinians fleeing the war in neighbouring Gaza.

Meloni hailed the EU-Egypt accord as a chance to give "residents of Africa" a chance "not to emigrate" to Europe. Put another way, an unnamed EU official told Politico, "we fund investment so we can create more economic activity in Egypt, so that the younger generation stays there". Egypt has largely shut off irregular migration from its north coast, but there has been a recent surge in those trying to cross to Europe via Libya.

Egypt's "strategic importance has been underscored by the war in Gaza", said Reuters, "where Egypt is trying to mediate between Israel and Hamas and increase deliveries of humanitarian aid; and by the conflict in neighbouring Sudan, which has created the world's biggest displacement crisis".

So European governments have "long been worried about the risk of instability in Egypt", said The Guardian. Greece and Italy are "particularly concerned" about the risk of another refugee crisis.

While enjoying broad support among EU member states, the approach is still "controversial", said The Times. The "lifeline" to Egypt's authoritarian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, "whose military regime has presided over the killing, torturing and imprisonment of opposition activists, as well as migrants, is under fire in Europe and could yet be blocked if MEPs vote against it in the European Parliament".

Last week, members of the European Parliament accused Brussels of "bankrolling dictators" in a bid to pander to the far-right.

Human Rights Watch said the EU's "cash-for-migration-control approach" exposes the bloc to "complicity in abuses, contradicts the EU's founding values, erodes its credibility as a principled global player, and emboldens the far right's demagogic narrative across Europe".

In another "growing controversy", said Politico, some critics have pointed to a "discrepancy between the bloc's approach to refugees from Ukraine and those coming from further afield".

What next?

Following a lull in 2022, the EU faced a surge in migrants arriving via the Mediterranean during 2023, and numbers are climbing again this year.

In recent months, the Greek islands of Crete and Gavdos have seen a steep rise in migrant arrivals – mostly from Egypt, Bangladesh and Pakistan – "raising concerns about a new Mediterranean smuggling route", said Al Jazeera.

To counter this, the EU has adopted a carrot-and-stick approach. As well as signing deals with Turkey, Tunisia, Mauritania and now Egypt – with Morocco to come – the bloc has increased resources for its border agency, Frontex. Some want to go further, though, with the conservative European People's Party (EPP) calling for a tripling in numbers of Frontex staff.

Whether this dual approach – of clamping down on people smugglers while working to improve conditions in origin countries – will work may depend on events outside the EU's control, namely the war in Gaza and status of Sudanese refugees.

According to UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, around 450,000 Sudanese people have fled to Egypt in the past year, with "fears of mass influx of Palestinians fleeing Gaza combining with economic turmoil to drive Egyptians to leave for Europe", said The Times.