The growing presence of China in Africa has captured the attention of both Africa and the West. As Chinese trade and investments have eclipsed those of Europe and the United States, their leaders have warned that Beijing is exploiting African resources, threatening African jobs, buttressing African dictators, and showing general disregard for human rights, good governance, and sound environmental practices. While leveling the same criticisms, African civil society organizations have noted with irony that the West has long engaged in similar practices.

Chinese interest in Africa—and Western concerns about Beijing’s influence—are not new. Understanding the current standoff requires an understanding of its history. The most recent wave of Chinese interest in Africa began during the Cold War. In April 1955, representatives of twenty-nine Asian and African nations and territories, and numerous liberation movements met in Bandung, Indonesia at the Conference of Asian and African States. Participants resolved to oppose colonialism and imperialism and to promote economic and cultural cooperation throughout the global south—then called the “Third World.” They voiced particular support for decolonization and national liberation in Africa. China played a key role in the conference and engaged with Africa in the Bandung spirit of African-Asian solidarity and cooperation. Between the early 1960s and the mid-1970s, China offered grants and low interest loans for development projects in Algeria, Egypt, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Tanzania, and Zambia. It also sent tens of thousands of “barefoot doctors,” agricultural technicians, and solidarity work brigades to African countries that rejected neocolonialism and had been rebuffed by the West.

In Southern Africa, where white minority rule persisted in settler colonies and Portugal resisted African demands for independence, Beijing provided liberation movements in Mozambique and Rhodesia with military training, advisors, and weapons. When Western countries ignored Zambian pleas to more effectively isolate the renegade regimes, China established the Tanzania Zambia Railway Authority (TAZARA) and built a railroad that permitted Zambia to export its copper through Tanzania, rather than white-ruled Rhodesia and South Africa.

During the Cold War, as China sought allies in the global arena, its policies were motivated primarily by politics. After the Cold War, however, China’s priorities changed. Beijing had embarked on a massive program of industrialization and economic development that transformed the Chinese economy into one of the world’s most powerful. Africa was no longer viewed as an ideological proving ground. Instead it was valued as a source of raw materials and a market for Chinese goods, ranging from clothing, cell phones and electronics to artificial intelligence systems. China’ relationship with Africa was no longer one that showed sympathy for its plight, but instead mimicked those of the colonial and Cold War powers. Countries were valued according to what they could offer China materially and strategically.

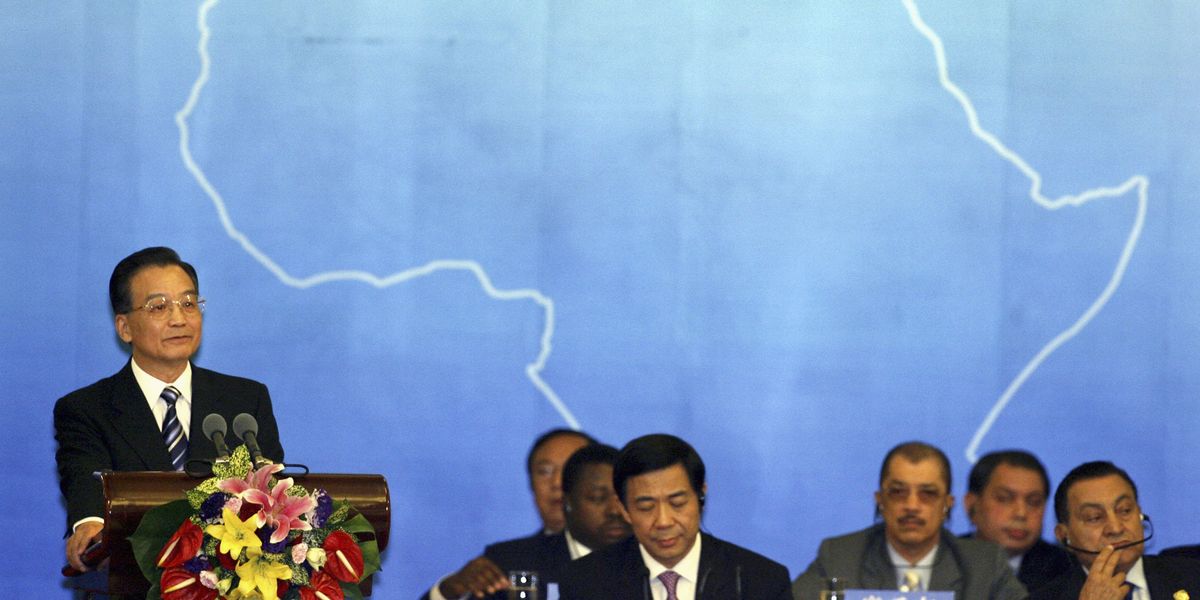

By the first decade of the twenty-first century, China had surpassed the United States as Africa’s largest trading partner, and more recently as Africa’s fourth largest source of direct foreign investment. In exchange for guaranteed access to energy resources, agricultural land, and strategic materials necessary to produce electronic devices and electric vehicles, China has spent billions of dollars on African infrastructure—developing and rehabilitating roads, railroads, dams, bridges, ports, oil pipelines and refineries, power plants, water systems, and telecommunications networks. Chinese enterprises have also constructed hospitals and schools and invested in clothing and food processing industries, agriculture, fisheries, commercial real estate, retail, and tourism. Recently, investments have focused on communications technology and wind and solar power.

Unlike the Western powers and the international financial institutions they dominate, Beijing has not made political and economic restructuring a condition for its loans, investments, aid, and trade. Although it has required that public works contracts be awarded to Chinese companies and that Chinese supplies be used, the agreements have not required a shift in economic models, adherence to democratic principles, respect for human rights, or the implementation of labor and environmental protections. While Beijing’s noninterference policies have been popular in ruling circles, civil society organizations have frequently criticized them. African labor, business, civic, and human rights organizations have observed that Chinese firms have driven African-owned enterprises out of business and employed Chinese workers rather than local ones. When they do hire African labor, Chinese businesses have paid poverty-level wages under conditions that have endangered worker health and safety. Moreover, the infrastructure projects have resulted in massive debts—although African countries still owe far more to Western powers and financial institutions than to China. Beijing’s practices, like those of Western powers, have resulted in a new wave of African dependency. Most importantly, Beijing has backed corrupt African elites in exchange for unfettered access to resources and markets, strengthening regimes that have pilfered their countries’ wealth, repressed political dissent, and waged wars against neighboring states.