Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English

Persistent economic and social disparities between urban centers and outlying communities present an ongoing source of instability for countries in the Maghreb.

Highlights

- The social and economic marginalization of communities in the periphery of each country of the Maghreb is an ongoing source of instability in the region.

- Security forces must distinguish between the threats posed by militants and ordinary citizens expressing grievances. A heavy-handed response is likely to backfire, deepening distrust of central governments while fueling militancy.

- Economic integration of peripheral communities is a priority. Such initiatives must deliver at the local level, however. Otherwise, perceptions of corruption and exploitation will reinforce perceived grievances.

Nearly a decade after the Arab uprisings, tempers in the outlying regions of the Maghreb are on the boil. Scarred by a history of states’ neglect, with poverty rates often more than triple that of urban areas, these frontiers of discontent are being transformed into incubators of instability. Bitterness, rage, and frustration directed at governments perceived as riddled with abuses and corruption represent a combustible mix that was brewed decades ago, leading to the current hothouse of discord and tumult. Into the vacuum of credible state institutions and amid illicit cross-border flows of people and goods, including arms and drugs, militancy and jihadist recruitment are starting to take root, especially among restless youth. The center of gravity for this toxic cocktail is the Maghreb’s marginalized border areas—from Morocco’s restless northern Rif region to the farthest reaches of the troubled southern regions of Algeria and Tunisia.

Governmental response has been parochial with an overemphasis on heavy-handed security approaches that often end up further polarizing communities and worsening youth disillusionment. At a time when governments are playing catch up against a continually shifting terror threat—and with the menace of returning Maghrebi fighters from Iraq, Syria, and Libya—the disconnect between the state and its marginalized regions threatens to pull these countries into a vicious cycle of violence and state repression. Breaking this spiral requires governments in the region to rethink their approach to their peripheral regions.

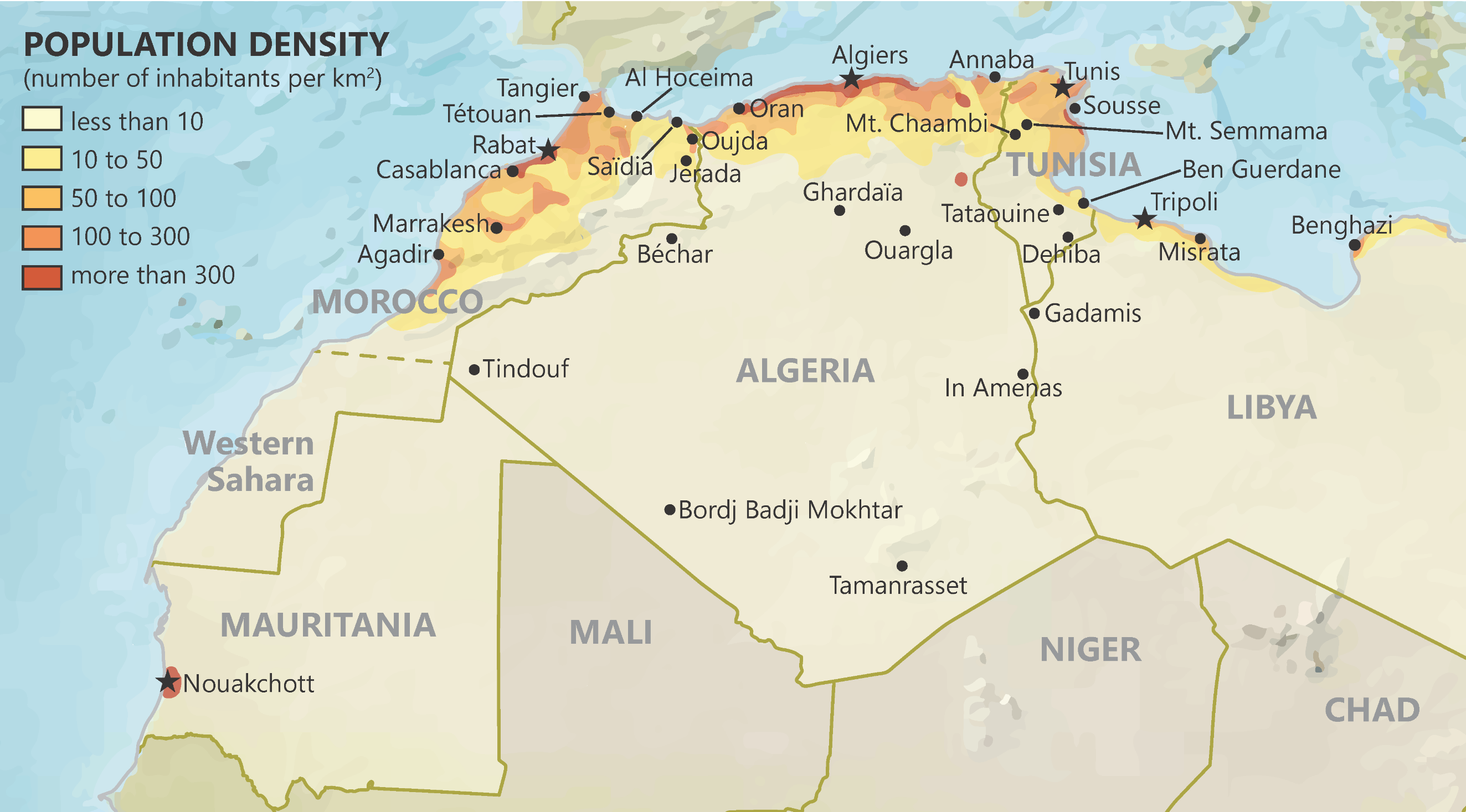

Countries of the Maghreb Region

Note: Population densities are shown for illustration purposes only and should not be relied upon for accuracy.

The transnational nature of security threats in the region also underscores the necessity for governments to develop their intelligence sharing and border security cooperation. Unfortunately, shared threats have been compounded by enduring interstate rivalries and closed borders. Since the mid-seventies, Morocco and Algeria have remained trapped in a zero-sum world. Their acrimonious rivalry over regional dominance and bitter feud over the Western Sahara have blocked progress on many of the burning issues that bedevil the Maghreb and Sahel. Whatever regional cooperation agreements there are tend to be limited and ad hoc. The challenge today is to broaden and make concrete these opportunities for cross-border cooperation.

Algeria Buffeted

For decades, an illusion of relative tranquility pervaded Algeria’s vast peripheral regions. This provided an eerie counterpoint to the intermittent agitation that animated the densely populated spaces in the country’s north. The Algerian south was suddenly catapulted to the forefront of public consciousness and national security concerns with the unprecedented terrorist targeting of Algeria’s energy infrastructure in 2013 at the In Amenas gas facility near the southeastern border with Libya. Forty workers were killed and hundreds held hostage.

Algeria’s oil and gas industry represents roughly 35 percent of GDP and 75 percent of government revenue. This strategic economic sector is largely based in the south, which encompasses more than 80 percent of the national territory but less than 9 percent of the population. This region, accordingly, looms large in Algeria’s security calculations. Yet, despite its strategic vitality, the south is often trivialized as a space of folkloric fascination and exotic, sometimes sinister, goings-on. The media tends to reinforce this narrative by inflating the stereotypes of Saharan communities as truculent tribes of dubious loyalty to the state.1

For Saharan communities, this prevalent discourse smacks of racial prejudice and a deliberate intention to justify their political and socioeconomic exclusion. It is not the terrain, climate, or presumed inherent laziness, lack of skills, and dubious nationalist credentials of the people of the Sahara that make them poor or engage in illicit flows at Algeria’s southern border with Mali and Libya. Rather, from the perspective of these communities, it is the neglect and pauperization of a rich region that has retarded its development and made it heavily dependent on smuggling and contraband as sources of daily subsistence.

The government’s laissez-faire approach to informal cross-border trade also contributed to making contraband a dominant economic activity in the south.2 This was a calculated strategy designed to tame the vast southern frontier, as contraband trade provided a lifeline to populations deprived of the financial benefits of their region’s natural resource endowments. The debut of terror groups and criminal organizations in the Sahara in the early 2000s revealed the potential pitfalls of this strategy, however. Regional terrorist networks and criminal organizations perfected the modes of operations, routes, and delivery methods that were first used by smugglers of innocuous commodities like petrol, cooking oil, corn flour, and powdered milk, and then, in the 1990s, by traffickers of cigarettes and weapons.

“For Saharan communities, this prevalent discourse smacks of racial prejudice and a deliberate intention to justify their political and socioeconomic exclusion.”

The shortcoming of Algeria’s lax management of its borderlands came after 2011. The Arab uprisings were a major catalyst in the awakening and politicization of the south. Protests against social exclusion, high unemployment, and environmental depredation have mushroomed across the Algerian Sahara since that time.3

Unfortunately, political disgruntlement and frustration with injustices are not always channeled into social mobilization and nonviolent protests.4 Some, especially disaffected youth, gravitate toward the transnational criminal, smuggling, and jihadi networks that have been established in Algeria’s south and its Sahelian periphery. The daring kidnapping of the governor of Illizi Province in southeastern Algeria in 2012 by locals involved in the protests against poor living conditions is illustrative. His subsequent transfer to Libya to be sold to elements of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) demonstrates the interconnectedness between grievances, criminality, and jihad.

Mounting sectarian and ethnic tensions, worsened by economic upheavals, have compounded troubles in Algeria’s south. The lethal intercommunal clashes that erupted in August 2013 in the border town of Bordj Badji Mokhtar exposed deep rifts between the Tuareg Idnan and Arab Berabiche communities. Never before had the area seen such an escalation of violence, which started when a young Tuareg, accused of theft, was murdered in an apparent vendetta.5 The region of Ghardaïa was also engulfed in waves of deadly violence between the Chaamba Arabs present in most of the Algerian south and the Mozabite Berbers of the Muslim Ibadi sect, an insular group with its own system of values, codes of conduct, and rules.6 The cause of the violence was attributed to disputes over resources, land, and migration.

Unfortunately for Algeria, the vast south is not the only border region exposed to internal and external shocks. Similar threats are mirrored along the Tunisian, Malian, and Libyan borders. Government tolerance of contraband and smuggling of commodities has provided terrorists and other criminal actors opportunities to exploit these informal cross-border routes. Algerian militants, for example, have used the limited oversight to build a safe haven in Mount Chaambi, Tunisia—a few miles from the Algerian border.7

Paradoxically, the only respite for Algeria can be found at its closed frontier with Morocco. In recent years, getting across the border has become quite difficult as both countries have tightened their control of smuggling routes and goods. In 2013, Algeria started digging trenches along its border with Morocco to deter smuggling of fuel. Not to be outdone, Morocco reacted a year later by building a 150-km-long security fence to strengthen its defenses against the flow of human smuggling and possible infiltration of terrorists from Algeria. Algeria accuses Morocco of flooding it with cannabis while Morocco complains about the flow from Algeria of African migrants and recreational drugs, namely amphetamine pills (Rivotril or Qarqobi in Moroccan colloquial Arabic).8

Despite the mutual recriminations, both countries’ fortification of their shared border seems to keep terrorist and violent criminal groups at bay even if smugglers continue to find ways to circumvent border controls.

Morocco Stable but Still Vulnerable

At first glance, Morocco’s borders seem to be the least exposed to the security dangers plaguing its neighbors in the Maghreb. The Kingdom has effectively minimized security challenges while continually enhancing its capabilities to prepare for risks that are increasingly volatile and unpredictable. With the exception of the Marrakesh bomb blast in 2011, Morocco has been safe from the terrorist attacks that have roiled Algeria and Tunisia. The country’s proactive security approach has made it harder for AQIM and other terrorist groups to establish a foothold in the country. That said, few security experts doubt that there are still security gaps in need of filling. The robustness of the drug and human smuggling networks active on Morocco’s borders is a cause of great concern. There is also a worrying increase in social tensions in the country’s peripheral regions, as exemplified by the monthslong protests that rocked the central Rif region of northern Morocco after the gruesome death of a fishmonger in October 2016.9

The most problematic regions in Morocco are located in the outlying south and north. A sizable chunk of the first is still mired in an unresolved dispute over Western Sahara. The vicissitudes of this dispute place the territory on a knife’s edge. Challenged from within by simmering pockets of dissent and from without by the increasing reach of violent extremist organizations and criminal networks operating in neighboring Sahelian countries, Western Sahara is one of the most heavily guarded and militarized places in Morocco. Parts of it have been sealed off since the 1980s with a 2,700-km trench-cum-wall (known as “the Berm”) that has effectively thwarted Algerian-backed Polisario fighters and transformed the balance of power in Morocco’s favor.

A rally for political reform in Morocco.

Nonetheless, the Polisario-controlled refugee camps in southwest Algeria boil with simmering anger and discontent. Former United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon worried about the vulnerability of young Sahrawis to recruitment by “criminal and terrorist networks.” In response, Moroccan authorities began fortifying their military presence on the border with Mauritania, as well as stepping up socioeconomic investments in the south of the country. In February 2016, King Mohammed VI launched an ambitious $1.8 billion plan to upgrade the region’s infrastructure and integrate it with the north of Morocco.

Similar government efforts to ease social tensions and mitigate the evolving threat of terrorism have been directed toward the Rif, a region with large pockets of alienation that extends from the bustling cities of Tangier and Tétouan in the northwest to the Algerian border in the northeast. The central part of the region, mostly Berber, is famous for its historic rebellious streak against central authorities. Meanwhile the western part, largely Arabophone, has gained notoriety for being a hub for migrant smuggling, drug trafficking, and recruiting aspiring militants to the conflict zones of Iraq and Syria. Out of the 1,500 Moroccans who reportedly joined the ranks of the self-proclaimed Islamic State an al Qaeda-aligned forces in Syria and Iraq, an estimated 600–700 hail from the north of the country.10

In response to these patterns, the government has increased its investment in vocational training, sociocultural centers, and rehabilitation programs to combat the increase in drug use and improve the lives of at-risk youth in the underprivileged neighborhoods of the northern cities. Since he assumed the throne in 1999, King Mohammed VI has also placed the economic development of the Rif, meaning “the edge of cultivated land,” as a top national security priority. The western Rif region, in particular, has seen a noticeable turnaround with significant investments in ports, roads, railways, air transportation, and water supply, as well as a range of other measures to attract private-sector investors to the newly created economic enclaves and industrial parks.

The most organized and resourced trafficking networks have moved from trafficking in the highly lucrative petrol trade to the smuggling of cigarettes, medicine, migrants, and drugs.”

The success in transforming the Tangier-Tétouan axis into an important manufacturing hub and commercial gateway has not, however, been replicated in the central Rif region where hundreds of villages still rely on rudimentary subsistence farming or cannabis growing to survive. To be sure, the new Mediterranean coastal road, known as “rocade du Rif,” which connects Tangier to Saïdia on the Algerian border, and the selective building and upgrading of main roads have improved the region’s road networks. But other promised big infrastructural plans such as the Manarat al Moutawassit (“Beacon of the Mediterranean”) development project in al Hoceima have been derailed.

The Moroccan government is also struggling to lift the northeast out of isolation. This region has been battered by the fortification of the closed border with Algeria.11 Seventy percent of the region’s economy depends on the informal sector, which employs about 10,000 people.12 The rest of the economy is based on remittances from Moroccans living abroad as well as on agriculture and mining (coal and iron), though these sectors have been lagging. Protests over the deaths of three young men extracting coal from abandoned mines in the restive eastern town of Jerada in January 2018 demonstrate the tension.13

The erection of security walls has not stemmed the illicit flow of all products between Algeria and Morocco. The most organized and resourced trafficking networks have moved from trafficking in the highly lucrative petrol trade to the smuggling of cigarettes, medicine, migrants, and drugs.14 Those that suffer the most are the majority of contrabandists who lack the resources and connections to circumvent state control or buy off border agents.

The Moroccan government has been trying for years now to develop an economic strategy to break the northeast’s geographic isolation and enhance its investment attractiveness. The most ambitious is the ongoing construction of the Nador West Med Port Complex and the free zone associated with it. The mega project aspires to replicate the success of the Tangier Med Port Complex in helping to strengthen the economic development of the northeast through the development of commercial, industrial, logistical, and services activities.

Nonetheless, while important progress has been made, the isolated communities in Morocco’s periphery remain a potential incubator for further instability.

Al Hoceima, Morocco

Tunisia Besieged

Tunisia is rightly lauded for the democratic progress it has made since the popular uprising that toppled longtime strongman Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in January 2011. But regional asymmetries pose significant challenges to the country’s nascent democracy. Poverty rates of 26–32 percent in rural areas are three times that in Tunis.15 The period since Ben Ali was ousted has not led to significant improvements in the economic situation of the border regions. Outside the wave of government hiring in the early days after the revolution and timid efforts to lure investors to these remote regions, their economic plight shows no sign of improvement. There is hope that the regionalization process—aimed at devolving power to regional and municipal authorities—can lead to a serious reassessment of regional development policies and a fair allocation of resources to these marginalized areas. Failure to do so threatens to aggravate social tensions at a time of returning battle-hardened Tunisian jihadists from Syria and Libya.16

“This growing disconnect between the state and its periphery is dangerous, threatening to perpetuate hard-line security approaches, the effects of which often result in more social tension and political violence.”

The fall of Ben Ali created a security vacuum and disrupted cross-border markets and trade networks, allowing for the creation of new opportunistic groups unknown to security officials and more willing to trade in drugs and firearms.17 For example, the transformation of Tunisia into a transit point between Algeria and Libya for the trafficking of cannabis, stimulant drugs, and alcohol affected the old contrabandists of legal commodities who saw a significant decrease in profits. The squeeze pushed some into the criminal marketplace to avoid insolvency.18

The encroachment of criminal activity was accompanied by a similar creeping intrusion of terrorist groups who sought to first establish a presence on the border to facilitate the departure of Tunisian recruits to Syria. This evolved into the creation of safe havens for those willing to fight in Libya and later return to undertake terrorist attacks in Tunisia proper, as happened with the perpetrators of the 2015 Bardo National Museum and Sousse attacks. On the western border with Algeria, a number of Tunisian militants managed in 2013 to gain a foothold in the rugged areas of Mount Chaambi and Mount Semmama, where soldiers have been killed and IEDs planted on local roads.19

Tunisian protesters denounce terrorism.

A rash of attacks on Tunisian security services, amplified by the dramatic assault by dozens of Islamic State-trained militants on security forces in the town of Ben Guerdane near the Libyan border in March 2016, has led to an increasing militarization of the border. This security-first approach has collided with the harsh reality of communities whose livelihoods depend on the free movement of people and goods.20 For example, the transborder dimension of social and tribal relations between Tunisia’s southeast and Libya’s west makes any disruptions to cross-border trade an explosive affair. In February 2015, the government’s closure of the border posts of Ben Guerdane and Dehiba triggered massive protests and the organization of a general strike. These protests were less about the state controlling its frontiers and more about the lack of viable alternatives to illicit cross-border trade and the government’s apparent nonresponsiveness to the population’s demands.

The government is seen as impeding one of the few sources of revenue available to border communities. This breeds bitterness among locals who believe that that government security measures come at the expense of their well-being. After all, the intensification of border enforcement is affecting only the most vulnerable people who are dependent on trade in contraband and lack the means and networks to circumvent border checks. The most powerful and resourced smuggling rings use the main roads and benefit from the connivance of Tunisian border patrol agents and other security officials.21

The rising militarization of the border seems to have the opposite effect of that intended. Instead of effectively curbing criminal activity and the trafficking of harmful substances, a militarized border has created more openings for corruption. For example, the inability of customs and border agents to provide security in the border region has led to an expanded role for the Army.22 The assumption of this new role elevates the potential for corruption within the Army, a development that risks tainting the image of one of the few state institutions that enjoys credibility and popular acceptance. It has also increased competition and distrust between the different services in charge of monitoring the borders.

“Overcoming this trust deficit between the security services and local communities is crucial for enhancing the effectiveness of the provision of security.”

The escalation of illicit activities along the borders, therefore, has justified the government’s militarization of the border and its clamping down on cross-border trade, but this has only served to exacerbate corruption, underdevelopment, and inequality. This pattern risks a deepening cycle of violence, organized criminality, and a backslide into repressive authoritarianism.

Ways Forward

While the degree of vulnerability to security threats facing governments in the Maghreb varies, none of these countries is immune from the mounting pressures of transnational militant organizations, criminal networks, and social tensions in their border areas.

The strengthening of states’ abilities to exert control over the entirety of their territories as well as the improvement of regional cooperation is, however, only one piece of the puzzle in tackling insecurities along the borders of the Maghreb. Security responses can never be a substitute for tackling the underlying drivers of insecurity: the political and socioeconomic marginalization of border communities. Many youths in the Maghreb’s border and peripheral regions have grown deeply frustrated, angry, and hostile toward state authority. This growing disconnect between the state and its periphery is dangerous, threatening to perpetuate hard-line security approaches, the effects of which often result in more social tension and political violence.

Following are some of priorities for action that emerge from this review:

Tackle the deep-seated grievances and resentments prevalent among peripheral communities and disadvantaged groups.

Strengthening government security capacities and boosting border controls are crucial but insufficient to protect against internal and cross-border threats. Morocco, in particular, but also Algeria and increasingly Tunisia deserve a pat on the back for neutralizing or containing the threat of terrorism within their borders. The significant weakening of the Islamic State in the region is a testament to the effectiveness of military and security responses. If history is any guide, however, the threat of terrorism will linger and remain a challenge in the Maghreb unless governments get serious about addressing the longstanding grievances and resentments prevalent among peripheral communities and disadvantaged groups. As the Tunisian experience amply demonstrates, anger at the persistence of social exclusion and regional disparities, combined with exposure to radical Salafi preachers, are important factors in understanding youth radicalization.

Resist replicating the old combination of repression and co-optation to smother popular mobilization.

From Tataouine in southern Tunisia to Ouargla in southern Algeria and the Rif city of al Hoceima in Morocco, this approach has shown its limits in subduing the cities and towns in upheaval. Emergency measures and promises of infrastructure projects may contribute to a lull in social mobilization, but their effects quickly evaporate if they fail to also genuinely respond to peoples’ demands for economic opportunity and ethical governance. The King of Morocco acknowledged as much in a speech during the opening session of Parliament on October 13, 2017:

[W]e have to admit that our national development model no longer responds to citizens’ growing demands and pressing needs; it has not been able to reduce disparities between segments of the population, correct inter-regional imbalances or achieve social justice.23

Improve community engagement skills of the police, gendarmerie, and other security forces to enhance state-society relations.

The persistent stigmatization of borderland and peripheral communities as troublemakers and outlaws and the trauma associated with aggressive and intrusive policing instill in young people profound feelings of humiliation and bitterness toward state authority. Overcoming this trust deficit between the security services and local communities is crucial for enhancing the effectiveness of the provision of security. The adoption of new rules and regulations to professionalize police training, recruitment, and promotion to advance cultural sensitivity to these communities is critical.

Recognize the historical specificity and geographic particularity of border regions.

In all countries of the Maghreb, border regions have suffered from decades of state neglect. Historic narratives have been manipulated to portray some outlying regions as archaic zones, full of dissidents and outlaws. Textbooks misrepresent traumatic events and downplay the significance of these regions’ roles in their countries’ histories. To heal past wounds, governments should develop an initiative to validate these communities’ contributions in history books, statutes, memorials, and exhibitions. If accompanied by development activities that cater to regional needs—and in the case of Tunisia and Algeria, the improvement in the management of natural resources and the investment of a fair portion of the profits from local resources into local projects—such gestures can help mitigate the sentiments of anger and resentment among peripheral communities. They can also help counter extremist recruitment.

Avoid overregulating the religious sphere and propagating religious boards as a means to combat extremism.

Overhauling the management of religion and reforming religious education in order to be in conformity with the tolerant and inclusive teachings of North African Islam is a worthy goal to combat the creeping menace of exclusivist ideologies. The risk with this approach, however, is that government policy becomes one of patronage of religious beliefs and practices. Perceived government propaganda to prop up state-sanctioned Sufism (Islamic mysticism) and religious authorities that pledge loyalty to state rulers suppress the development of competent clerics and credible religious institutions that can tear down violent interpretations of Islam. Worse, it taints the religious establishment by association with untrusted government authorities. Part of the lure of militant ideologies and violent extremist groups lie in their anti-systemic rhetoric and their ability to tap into anti-establishment anger. This was clearly demonstrated in the case of Tunisia when becoming a member of Ansar al Sharia was tantamount to joining a revolutionary movement intent on rupturing the generational and institutional order.

Enhance regional cooperation.

Given the decades-long rivalry between Morocco and Algeria, strengthening regional cooperation will likely require pursuing incremental objectives. These include focusing on specific security matters such as the exchange of intelligence information on drugs, arms, and human smugglers as well as Maghrebi fighters in Syria and Libya. The Algerian-Tunisian border security cooperation reflects this kind of cautious collaborative approach.

Notes

- ⇑ “Le Grand Sud, l’autre Algérie,” Jeune Afrique, May 14, 2012.

- ⇑ Tarik Dahou, “Les marges transnationales et locales de l’État algérien,” Politique africaine No. 137 (2015), 7-25.

- ⇑ Naoual Belakhdar, “’L’éveil du sud’ ou quand la contestation vient de la marge,” Politique africaine No. 137 (2015), 27–48.

- ⇑ Salim Chena, “L’Algérie et son Sud: Quels enjeux sécuritaires?” Institut français des relations internationales (November 2013).

- ⇑ Isabelle Mandraud, “Menaces sur le ‘Sud tranquille’ algérien,” Le Monde, September 3, 2013.

- ⇑ Houria Alioua, “Folie meurtrière au Mzab : 25 morts,” El Watan, July 8, 2015.

- ⇑ Sherelle Jacobs, “Shadow of Jihadi Safe Haven Hangs Over Tunisia, Algeria,” World Politics Review, May 21, 2013.

- ⇑ Querine Hanlon and Matthew M. Herbert, “Border Security Challenges in the Grand Maghreb,” Peaceworks No. 109 (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, 2015).

- ⇑ Aida Alami, “Morocco’s Stability Is Roiled by Monthslong Protests Over Fishmonger’s Death,” New York Times, August 26, 2017.

- ⇑ Nadia Lamlili, “Maroc : de Tanger à Ceuta, sur les traces des jihadistes,” Jeune Afrique, December 14, 2015.

- ⇑ Marie Verdier, “Oujda, un drame frontalier dans le nord-est du Maroc,” La Croix, July 13, 2017.

- ⇑ Michel Lachkar, “Le futur port de Nador, espoir de désenclavement du Nord-Est marocain,” Géopolis Afrique, June 6, 2016. end,e and practices that are commitetd of Tunsia when tions of ISlam ims n

- ⇑ “New protests emerge in eastern Morocco,” Economist Intelligence Unit, January 25, 2018.

- ⇑ Chéro Belli, “Une frontière poreuse, malgré les barrières entre l’Algérie et le Maroc,” Dune Voices, February 1, 2017.

- ⇑ “Note d’orientation sur les disparites regionales en Tunisie,” World Bank (July 2015).

- ⇑ “Tunisia says 800 returning jihadists jailed or tracked,” Agence France-Presse, December 31, 2016.

- ⇑ Anouar Boukhars, “The Potential Jihadi Windfall from the Militarization of Tunisia’s Border Region with Libya,” CTC Sentinel 11, no. 1 (2018), 32-36.

- ⇑ Hamza Meddeb, “Les ressorts socio-économiques de l’insécurité dans le sud tunisien,” Fondation pour la recherche stratégique (June 2016).

- ⇑ Sarah Souli, “Border Control: Tunisia Attempts to Stop Terrorism with a Wall,” VICE, November 16, 2015.

- ⇑ Anouar Boukhars, “The Geographic Trajectory of Conflict and Militancy in Tunisia,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (July 2017).

- ⇑ Aymen Gharbi, “Tunisie: Entretien sur l’économie de Ben Guerdane avec Adrien Doron, chercheur en géographie,” Huffington Post International, March 22, 2016.

- ⇑ Meddeb.

- ⇑ “Full Text of HM the King’s Speech at Parliament Opening,” Morocco’s Ministry of Culture and Communication Web site, October 13, 2017.

Anouar Boukhars is a nonresident scholar in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Middle East Program and associate professor of international relations at McDaniel College in Westminster, Maryland.