Executive Summary

Executive Summary

Al Qaeda is expanding across Africa. The Obama administration made fighting the Islamic State of Iraq and al Sham (ISIS) the primary—nearly exclusive—focus of its counterterrorism operations after its June 2014 seizure of Mosul, Iraq. Theaters with a large ISIS presence (Iraq, Syria, and to a lesser extent Libya) received attention. Those with a minimal ISIS footprint, such as Somalia, did not.

Al Qaeda has taken advantage of American disinterest to expand the size and strength of its affiliates around the world. The Trump administration must reverse this policy, recognize the present and long-term danger al Qaeda poses to the US, and act against al Qaeda groups before the cost of action and the price of inaction rise too high. A small investment in Somalia today can yield a large return in the future in the form of attacks averted and wars we do not have to fight.

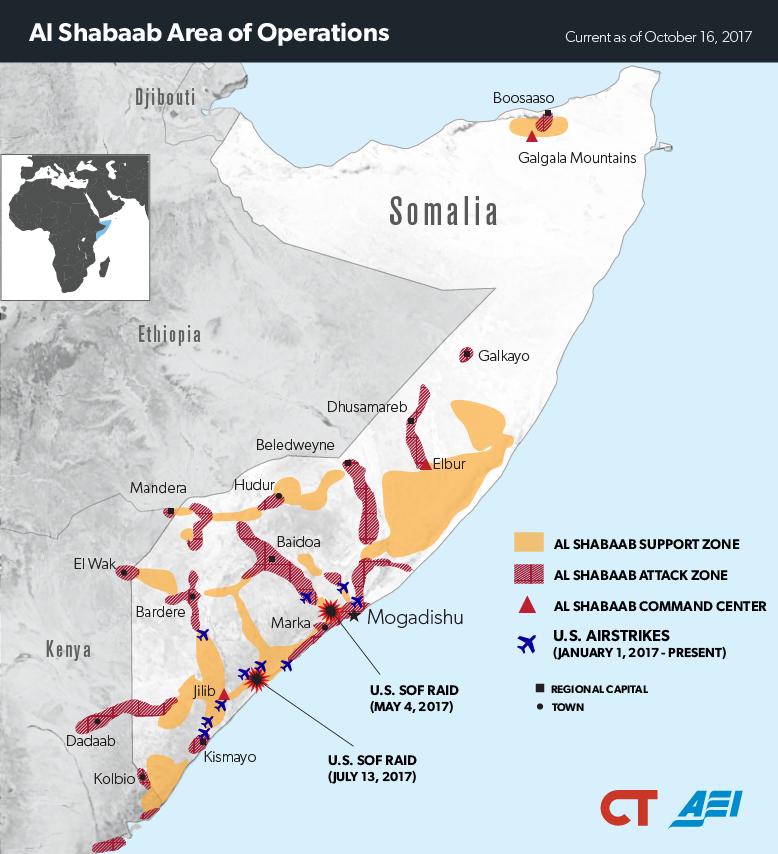

Al Shabaab, al Qaeda’s branch in Somalia, is resurgent and set to make additional gains in 2017. It rebuilt its strength after the losses it sustained in 2012 and 2013 by exploiting the local grievances and conflicts of the Somali population. It aims to operate throughout East Africa and is actively building a support base in Kenya. It is also improving its attack capabilities. It managed to smuggle a concealed explosive device aboard an airplane last year that detonated, but fortunately failed to bring the plane down. This attack was a step-change in the group’s tactics that demonstrates its continued intent to conduct international and not merely local attacks.

Al Shabaab sits on a key line of communications between the Middle East and Africa—a link that al Qaeda has sought to maintain over the years. It interacts with al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula in Yemen, as well as the network of al Qaeda and ISIS groups operating throughout Egypt, Libya, and Sudan and into Mali and Nigeria. Al Shabaab’s strength contributes to the strength of the al Qaeda network overall.

The US must invest more energy and resources in the fight against al Shabaab to prevent it from becoming an even greater threat. US strategy relies heavily on ground partners—the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) peacekeeping forces and Somali security forces—to combat al Shabaab, and these partners need support. The Pentagon is recommending increased collaboration between US Special Operations Forces (SOF) and Somali forces, as well as reduced restrictions on airstrikes against al Shabaab. The Trump administration should accept this recommendation.

The US should also work with AMISOM forces to improve their operations and ensure that troop contributing states do not withdraw troops prematurely from the mission, which would rapidly collapse the gains made against al Shabaab. The Somali Federal Government (SFG) requires assistance, which the US should help provide, to regain legitimacy and address these challenges within the Somali border. Supporting the SFG’s initiatives and working to expand the Somali state would limit the space in which al Shabaab has freedom of operations. There is no need to deploy American combat forces to Somalia at this time, and a sound strategy of supporting and encouraging our local partners can obviate the need for such deployments in the future.

The US should work actively to maintain pressure on al Shabaab to prevent it from regaining its shadow state in Somalia. Any al Qaeda shadow state anywhere contributes to the group’s global ability to plan, prepare, and execute attacks against the US homeland and Americans abroad. American national security interests are linked to the strength of al Shabaab, and so the US must stay in the fight.

Introduction

Al Shabaab militants detonated a truck filled with explosives in a busy marketplace in Mogadishu, Somalia, killing at least 30 people, on February 19. The explosion was so powerful that of a family of 12 killed in the blast, only the mother’s remains could be identified.[1] The blast came one day after newly elected Somali President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmajo predicted that al Shabaab would be defeated within two years. Farmajo’s prediction seems improbable.

Al Shabaab is al Qaeda’s affiliate in East Africa. It will likely gain ground and strength in 2017 despite the limited US support for proxies fighting it, Farmajo’s optimism notwithstanding.[2] Its resurgence will strengthen the regional and global al Qaeda movement, already expanding as American and Western attention has become riveted on ISIS over the past few years.[3] Its gains will make the task of ultimately defeating al Qaeda much harder.

Somalia occupies an important position astride lines of communication from Yemen, where al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula is prospering in the midst of a civil war, to Salafi-jihadi groups in Libya, Mali, and Egypt. It is part of the larger untold story of the dramatic increase in the power and influence of al Qaeda and like-minded groups throughout Africa that provide resources and capabilities to local, regional, and global attack cells. Losing ground to al Qaeda in Somalia is a loss for American strategy against ISIS and al Qaeda globally.[4]

Al Shabaab arose following the collapse of governance in Somalia and the emergence of civil conflict, as well as from its ability to pose as an indigenous resistance to foreign invasion. Its arc thus mirrors those of many other al Qaeda and ISIS affiliates. Moreover, it will continue to benefit from those conditions despite superficial governance improvements.

The forces that reduced al Shabaab’s ability to operate and hold ground have come primarily from Somalia’s neighbors—Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, and Burundi. Efforts to build an indigenous Somali military have been halting and offer no prospect of producing a force that can replace those external militaries. But spreading famine and domestic political considerations will increase the pressure on those states to bring some or all of their troops home, even as al Shabaab continues its counteroffensive.[5] The stage is set for the collapse of all or most of the gains that had been made against the Salafi-jihadi movement in Somalia over the coming years, to the benefit of al Qaeda.

Al Shabaab’s Rise in Somalia

Al Shabaab arose out of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), a collection of shari’a courts that governed most of Somalia by 2005.[6] A US-backed Ethiopian invasion overthrew the ICU and began reinstalling a federal government in the country in 2006.[7] Al Shabaab organized and armed the resistance against the Ethiopian presence, ultimately unifying a notable portion of the insurgency under its control.[8]

Ethiopian forces withdrew from Somalia in January 2007 after decimating the ICU and handed its bases over to the newly created African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). Al Shabaab quickly overran AMISOM positions, however, setting the group on course to control most of southern and central Somalia by 2009. It incorporated minority clan militias and became the strongest military force in the country.[9]

Al Shabaab governed the territory it held and was an existential threat to the Mogadishu-based Transitional Federal Government (TFG), set up in the wake of the Ethiopian intervention to set conditions for the emergence of a new Somali government.[10] Al Shabaab enforced its interpretation of shari’a in its territory and created administrations to rule locally. It controlled nearly all of Somalia’s capital in 2010, apart from a few blocks from the airport to the Villa Somalia, where the TFG hunkered down.[11] AMISOM’s troops were not sufficiently trained or equipped to respond to al Shabaab’s threat and suffered significant casualties.[12] Al Shabaab consolidated control over south-central Somalia at the end of 2010 by merging with Hizb al Islam, an Islamist militia that had previously both cooperated with and fought against al Shabaab.[13]

However, momentum shifted against al Shabaab in the fall of 2011. A severe drought and subsequent food shortages in Somalia, as well as improvements to AMISOM’s fighting abilities, strained al Shabaab. The group announced its withdrawal from Mogadishu in August 2011, but retained control elsewhere in the country.[14]

Kenyan forces invaded Somalia in October 2011 after a series of al Shabaab kidnappings threatened Kenya’s tourism industry.[15] Ethiopian troops also reentered Somalia along the common border.[16] Along the Somali border, Kenya and Ethiopia sought to establish buffer zones controlled by friendly forces that could contain al Shabaab inside Somalia.[17] The Kenyan troops were also moved under the AMISOM mandate in July 2012 to legitimize their continued operations in Somalia.[18] Kenyan forces captured the strategic port city of Kismayo in September 2012 after a protracted campaign.[19] Al Shabaab reverted to insurgent operations after 2012, although the group retained its safe havens in the Somali hinterland.[20]

Kenyan success resulted in part from internal tensions within al Shabaab. The killing of Osama bin Laden in May 2011 had triggered changes in the group. Ahmed Abdi Godane, the leader at the time, had petitioned bin Laden to recognize al Shabaab as an al Qaeda affiliate, without success. Bin Laden’s successor, Ayman al Zawahiri, granted the request in a public declaration in February 2012.[21]

These discussions reflected the reality that Godane was shifting al Shabaab from a Somalia-focused al Qaeda organization into a regional one. He purged the group’s high-level operators and leaders after bin Laden’s death.[22] The purge particularly targeted members of al Qaeda in East Africa (a rival for al Shabaab’s position in the al Qaeda organization) and those close to al Shabaab deputy leader Mukhtar Ali Robow, who emphasized al Shabaab’s nationalist fight for Somalis. Godane’s purges split the movement, leading senior leader Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys to split Hizb al Islam from al Shabaab in September 2012 in opposition to Godane’s focus on a global jihadist mission.[23]

Many mistook al Shabaab’s decline as a permanent setback. President Barack Obama went so far as to say in mid-2014, “This strategy of taking out terrorists who threaten us, while supporting partners on the front lines, is one that we have successfully pursued in Yemen and Somalia for years.”[24]

The group reset after its losses, however, and began a campaign to drive Kenyan troops from Somalia and spread its insurgency into northern Kenya. Al Shabaab attacked the Westgate Mall, a high-end shopping center frequented by Westerners, in September 2013, killing at least 67 people.[25] The tactical team that conducted the attack was well trained, and al Shabaab caught the region by surprise. An attack against a university in the military town of Garissa 18 months later killed 147 people.[26] Al Shabaab sought to raise the political cost of Kenyan troops in Somalia through the mass-casualty attacks. It also began an underreported effort in northern Kenya to inspire the Somali-Kenyans to rise up. Al Shabaab ran a “seize-and-sermon” campaign in which it would temporarily seize control of the local mosque and deliver its message before Kenyan security forces arrived.[27]

Continued governance and security gaps in Somalia permitted al Shabaab to rebuild in its strongholds and prepare for a counteroffensive against AMISOM and Somali forces. The Somali Federal Government (SFG) was struggling to secure legitimacy among Somalis because it did not have the resources or capacity to provide basic services beyond the capital. Additionally, local power conflicts flashed as opposing factions sought to establish themselves as the local authority in advance of SFG efforts to stitch Somalia back together. AMISOM and Somali forces did not pursue al Shabaab into the hinterlands because of force size constraints and, probably, lack of political will. Al Shabaab therefore still had access to financial resources, could recruit and train new foot soldiers, and could operate relatively freely outside of major populated centers.

US Strategy and Its Challenges

The United States has sought to minimize the American footprint and investment in Somalia since 9/11. American policymakers remain traumatized by the 1993 Black Hawk Down incident, diminishing the already-negligible enthusiasm for intervening in Somalia. The Bush and Obama administrations have therefore relied instead on limited direct action operations against key individuals threatening American interests and on support for local partnered forces to restore stability to the country under an acceptable government, as Obama noted in his 2014 statement. The US has also invested in Somalia’s neighbors, particularly Kenya and Ethiopia, to build their capabilities against al Shabaab.

American strategy against al Qaeda in Somalia thus depends on the sustained military activities of some of the poorest countries in the world, which are facing their own internal social, political, and economic challenges and blowback from their involvement in Somalia. That is not likely to prove a winning program over the long term.

US Direct Action Operations.

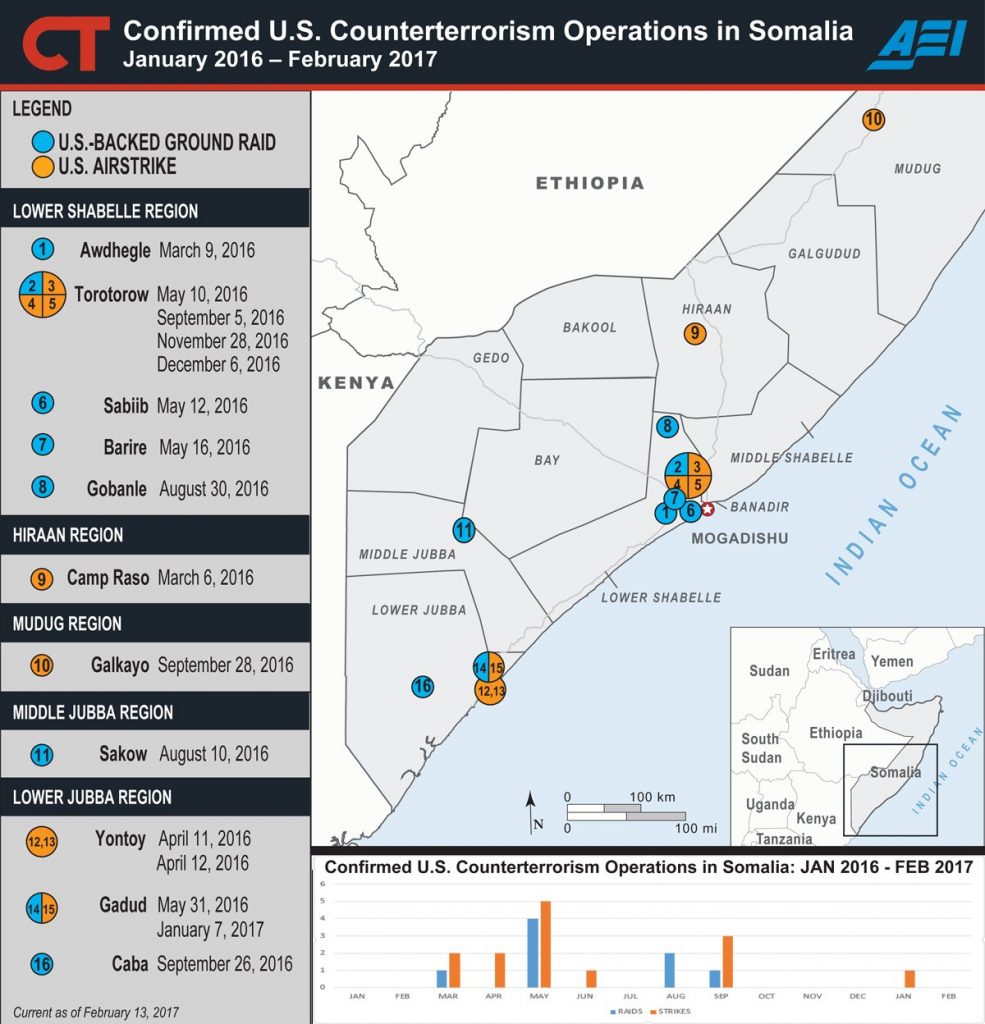

US direct action operations in Somalia targeted only senior al Qaeda operatives who received sanctuary from al Shabaab until the Obama administration expanded its targeting to include senior al Shabaab leadership.[28] The Bush administration ordered the capture of Suleiman Abdallah from his hospital bed in 2003 and expanded to airstrikes and raids, ending in 2008 with the death of Aden Hashi Farah, the leader and a founding member of al Shabaab.[29] Obama administration operations began with a US Navy SEAL raid that killed Saleh Ali Saleh al Nabhan, one of the al Qaeda planners of the 1998 East Africa embassy attacks. A US airstrike killed Godane himself in September 2014.[30] US Navy SEALs attempted to capture Abdulkadir Mohamed Abdulkadir during an amphibious assault on the port city of Barawe in October 2014 but aborted the mission for fear of causing civilian casualties. The Obama administration announced in late 2016 that it interpreted the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force against al Qaeda to include al Shabaab.[31]

However, these efforts have not deterred or prevented al Shabaab from expanding its aims and improving its means of pursuing them. The group still intends to conduct external attacks despite Godane’s death. It tried to bring down a plane taking off from Mogadishu’s Aden Adde International Airport with an improvised explosive device disguised as a laptop in February 2016.[32] It likely obtained this capability from al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula in Yemen.

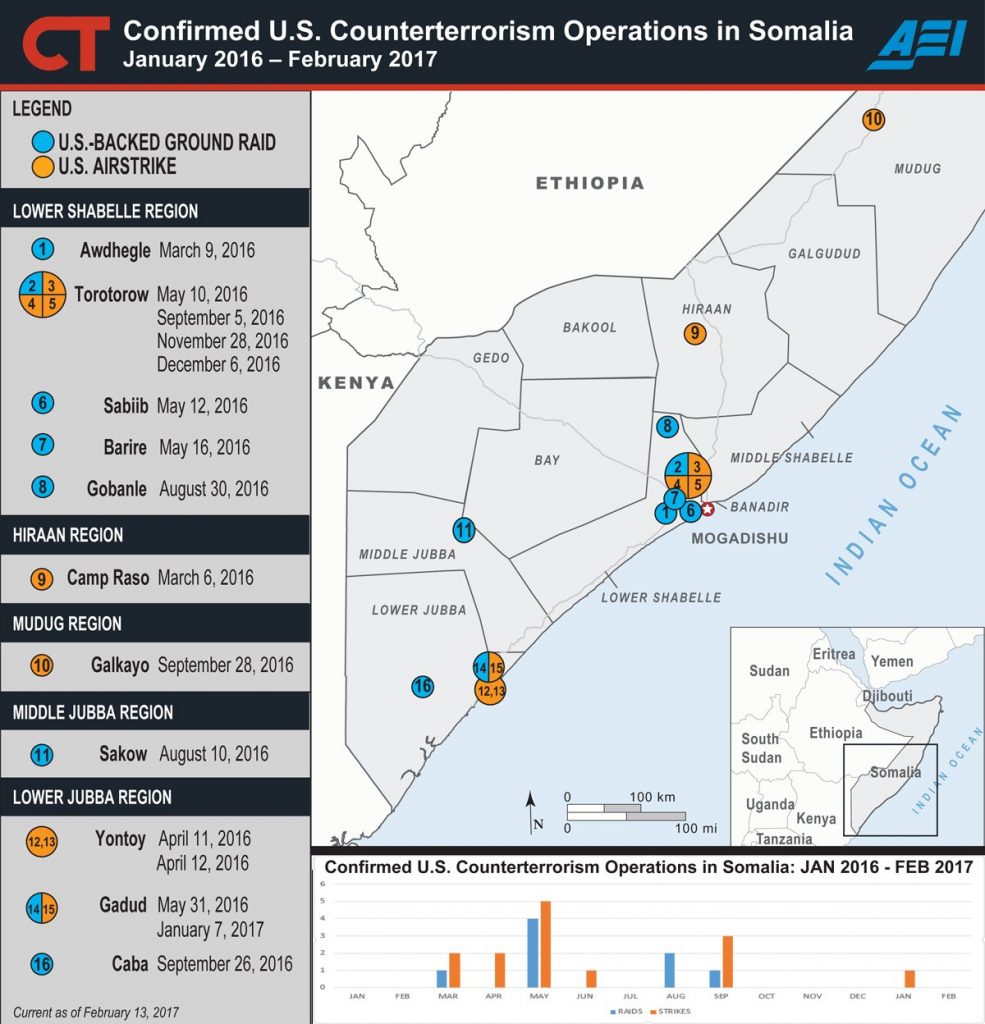

The US appears to have increased its operations against al Shabaab in response, at least temporarily. The Obama administration began to target mid- and low-level operatives, starting with an airstrike on March 5, 2016, that killed approximately 150 fighters at an al Shabaab training camp 120 miles north of Mogadishu.[33] Pentagon officials stated the al Shabaab forces posed an imminent threat to US forces in the area, where they were working directly with local partners.[34] The US also provided air transportation and air support to the Gashaan forces on “Somali-led” direct action raids throughout 2016. The raids and airstrikes likely resumed in January 2017 after a pause in the fall of 2016 when a US airstrike killed 10 non-Shabaab local security forces in Galkayo, Somalia, in September 2016. Still, US-backed raids and airstrikes have yet to return to the same frequencies observed in early 2016 since the September 2016 Galkayo strike.

Al Shabaab's Lower Shabelle Campaign

In any event, limited direct action strikes such as these can only hope to disrupt senior leadership and planning for external attacks. American strategy for containing and ultimately defeating al Shabaab relies on AMISOM and the Somali National Army. The United States trained and equipped AMISOM contingents and helped develop elite Somali counterterrorism units.[35] AMISOM currently includes about 22,000 troops from five African countries: Uganda (6,000), Burundi (5,400), Ethiopia (4,300), Kenya (3,600), and Djibouti (1,000).[36] AMISOM also receives significant American logistical and intelligence support.[37] The US gave nearly $1 billion to AMISOM forces and the UN mission in Somalia between 2007 and 2015 alone.[38]

AMISOM forces nevertheless face serious challenges operating in Somalia. Much of the Somali populace sees the AMISOM contingent, and particularly the Kenyan and Ethiopian forces, as an occupying force. AMISOM forces’ undisciplined responses to al Shabaab attacks frequently cause civilian casualties and reinforce this narrative of reckless invaders.[39] AMISOM divides its area of operations into five sectors, each run by a different national contingent (a common practice in multinational operations). It is encountering the same difficulties resulting from this approach that other multinational forces have faced, particularly the problem of moving reinforcements across seams.

Both the AMISOM and Somali National Army (SNA) forces also suffer from operating dispersed bases over a wide area. They have struggled to hold the positions and lines of communications needed to sustain this posture. They often occupy key positions to secure major populated areas, such as Kismayo, Beledweyne, Baidoa, and Dhusamareb, but do not hold the territory between these positions, allowing al Shabaab to operate and disrupt their communications. Moreover, they periodically withdraw from newly seized populated centers when pressured, allowing al Shabaab militants to return without resistance.

AMISOM itself can only be a temporary solution, as all participants recognize. Somalia can become stable only when its own military and police forces can secure their own territory. That prospect, however, seems to be a long way off.

The US has trained Somalia’s elite special forces units, known as Gashaan (“lightning”), which includes the elite Dannab (Alpha) brigade.[40] These units accompany US forces on direct action missions, respond to hostage crises, and most recently have been tasked with protecting President Farmajo.[41] The Gashaan brigade is a small but effective fighting force. The rest of the SNA is much less combat-ready, despite the continued efforts of AMISOM, the US, and other Western partners.

The SNA resembles a collection of regional militias more than a unified national force. It remains undermanned, poorly equipped, and ineffective. Officials tell stories of SNA forces training without firearms.[42] SNA forces sometimes flee their positions at the first rumors of approaching al Shabaab forces.[43] Although the capability and capacity of US-partnered ground forces to pursue al Shabaab in Somalia has improved over time, the SNA is years away from being an effective national military force on its current trajectory.

A Weak Partner in the Somali State.

Military and police forces can defeat an insurgency only if they operate under the direction of a government that the population sees as legitimate. Somalia is in dire straits in this respect. It ranked first in the world for perception of corruption among all nations in 2016.[44] It lacks the basic institutions needed to enforce its laws. Counterfeit Somali shillings and US dollars flood marketplaces in Mogadishu.[45]

Governance gaps are many, and when the SFG and AMISOM retake towns from al Shabaab, the SFG does not have the capacity to govern or even provide basic services. Al Shabaab returns to govern when AMISOM or Somali forces withdraw. It brutally punishes those accused of collaborating with the foreigners or the SFG, discouraging local populations from throwing their support behind the central government. This negative cycle must be broken for the SFG to succeed.

Somalia’s much-delayed 2016 national election process dragged on into early 2017.[46] Corruption and voter suppression were prevalent.[47] Multiple close contests ended in armed standoffs.[48] Some reports suggest al Shabaab did not seriously attempt to disrupt the election season because al Shabaab rule is seen as more fair and transparent.[49] Signs of optimism still linger from the election of dual Somali-American citizen Farmajo, although he will need to show progress to retain popular support. With true democratic elections promised by 2020 (this last one was mediated by the clans), the SFG and Farmajo have little time to develop a proper electoral system and the local governance required to sustain it. Farmajo’s popularity notwithstanding, the problems with the election that brought him to power have soured many Somalis on the democratic experiment and will likely make overtures from al Shabaab more appealing.

Nature is conspiring against the young Somali government as well. The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWSNET) predicts that the ongoing drought in East Africa will cause severe food shortages in southern and central Somalia, likely mirroring the conditions seen in 2011.[50] Two consecutive inadequate rainy seasons are already straining food supplies for many segments of the Somali population. There are already reports of deaths in southern Somalia, and the crisis is worsening.[51]

A major humanitarian crisis would overwhelm the SFG’s capacity to provide, coordinate, and administer relief, which will generate additional grievances that al Shabaab could exploit. Additionally, al Shabaab could use its control of terrain to reestablish itself. Al Shabaab heavily taxed humanitarian aid that entered its territory in 2011 and distributed the goods itself. Its ban against Western aid, however, did lead to a surge of anti-Shabaab sentiment and also surfaced rifts in the leadership.[52] If al Shabaab learned its lesson from 2011, it stands to benefit a great deal from the misery of the Somali people.

Regional Instability Threatens AMISOM Partners.

Finally, external pressures on AMISOM troop-contributing countries (TCCs) have destabilized AMISOM’s commitment to Somalia. Support for a sustained deployment in Somalia among the TCCs is waning as domestic factors increasingly play a role. AMISOM faces both financial and logistical problems. The African Union has struggled to keep up with payment schedules for AMISOM soldiers after the European Union cut its financial support by 20 percent in January 2016.[53] TCCs did not meet a January 2017 AMISOM request for an additional 9,000 troops to accelerate the training of Somali security forces before the end of AMISOM’s mandate.[54]

Moreover, TCCs have started to pull their forces out, despite the clear evidence of al Shabaab’s resurgence and the patent inadequacy of the SNA. Sierra Leone withdrew its troops from AMISOM in January 2015 to respond to the Ebola epidemic.[55] Burundi and Uganda have also threatened to pull out of AMISOM prematurely, which could collapse the force. The planned withdrawal is scheduled to begin in 2018.[56]

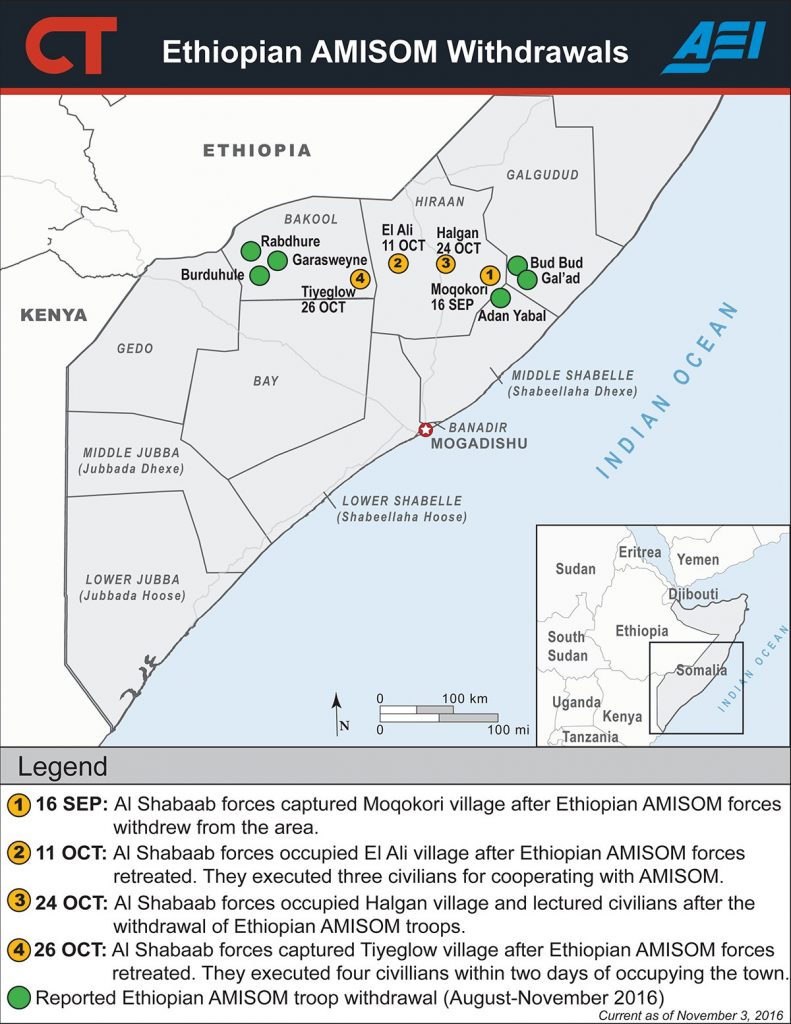

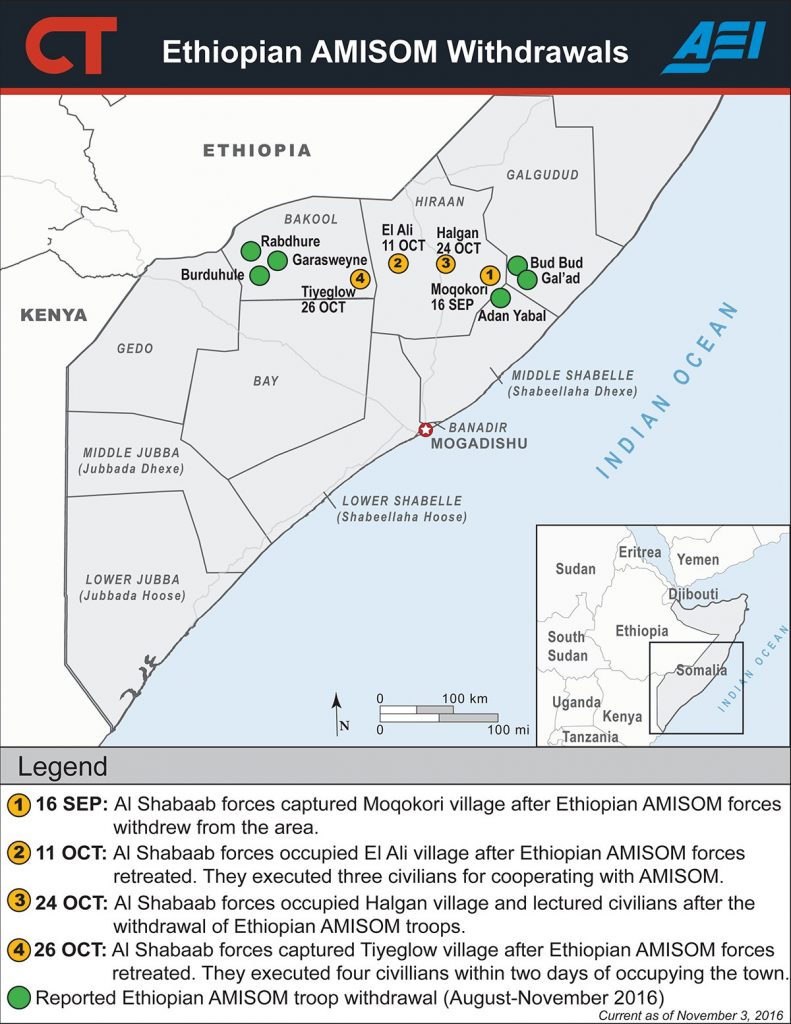

Ethiopia has also reduced its deployment to Somalia in response to domestic unrest. Protests against the government began in the Amhara and Ogaden regions in November 2015, sparked by land disputes and a sense of social marginalization.[57] Ethiopia began to withdraw about 3,000 soldiers operating in south-central Somalia (not as part of the AMISOM mandate) in late summer 2016 after protests escalated. It has since withdrawn troops from its AMISOM contingent after protests intensified in November 2016.[58] These Ethiopian troops have deployed to the Amhara region to suppress protests and have clashed with local militias near Gondar.[59] Ethiopia is unlikely to redeploy forces to Somalia at this time.

Ethiopian AMISOM Withdrawals

Burundi’s commitment to AMISOM is particularly unstable after Burundian President Pierre Nkurunziza cracked down following an attempted coup in May 2015.[60] President Nkurunziza called for the withdrawal of all Burundian forces in Somalia in early January 2017 due to a dispute with the EU, which refused to run its payments of the Burundian AMISOM contingent through the central Burundian government.[61] The African Union brokered a last-minute deal to stop the Burundian withdrawal on January 19.[62] However, ongoing anti-regime protests that began during the 2015 election cycle also continue to test Burundi’s commitment to AMISOM. More than 500 people have been killed in the protests, and 270,000 have left the country, according to UN estimates, increasing the likelihood that Burundi will withdraw troops from AMISOM and use them for domestic matters.[63]

Uganda has also threatened to pull its troops from Somalia, but this threat is likely posturing from President Yoweri Museveni, based on rhetoric over the past few years. Former Ugandan Chief of Defense Forces General Katumba Wamala suggested in June 2016 that Uganda might withdraw troops before the planned exit in 2018.[64] Uganda has since participated in a three-day meeting in November 2016 with AMISOM military officers and SNA commanders, and it rotated 2,745 new soldiers into Somalia in December 2016 in anticipation of the presidential election.[65] Wamala also warned his successor, General David Muhoozi, against withdrawal from AMISOM.[66] Uganda recently called for a review of AMISOM’s funding situation, but did not indicate that withdrawal was on the table.[67] Much of the talk of withdrawing forces among the TCCs are attempts to secure a larger portion of the AMISOM funding, but this political maneuvering shows a tenuous commitment to the AMISOM mission that has repeatedly been disrupted by funding disputes.

The Kenyan deployment in Somalia remains controversial among Kenyans, many of whom blame the intervention in Somalia for al Shabaab’s increased attacks inside of Kenya. Closing the Dadaab refugee camp, which Kenyan officials say is a hotbed of al Shabaab activity, remains a contentious issue.[68] A Kenyan judge ruled in February 2017 that Kenya’s current plan to close Dadaab violated multiple articles of the Kenyan constitution, but the government immediately appealed the ruling.[69] The country will hold presidential elections in August 2017, and the economic and security cost of Kenya’s contributions to AMISOM are very likely to be key issues in the political debates. Kenya has sought for AMISOM to cover the cost of its logistical support to the Kenyan troops deployed inside Somalia to help with the cost of the intervention. The Kenyan elections may determine whether Kenya sustains its AMISOM membership.

AMISOM is thus a fragile military coalition among weak, poor, and domestically challenged states. It has been unable to defeat al Shabaab or prevent it from regaining lost ground, and it is more likely that AMISOM will weaken than that it will be reinforced. The local partners on which US strategy relies are thus likely unable to achieve American national security requirements and may not even be able to protect their own interests or, in the case of the Somali Army and government, lives.

Al Shabaab’s Resurgence in 2017

Al Shabaab is regaining ground and strength, meanwhile, and may be preparing to launch a significant counteroffensive beyond targeting AMISOM and SNA forces to regain momentum in Somalia in 2017. It has developed the ability to conduct complex raids against hard AMISOM targets, causing significant casualties. It has rebuilt its ability to conduct mass-casualty spectacular attacks in Mogadishu and sustained small-arms attacks against Somali government and security officials. Al Shabaab expanded its area of operations into northern Kenya and is reemerging in populated centers in southern and central Somalia. It is poised to exploit regional and local political and security conditions. In the aftermath of Somali federal elections, al Shabaab has reaffirmed its vow to target the new government and destabilize the existing order.[70]

Insufficient AMISOM troop levels leave AMISOM units isolated in forward operating bases in the Somali hinterland. Al Shabaab has taken advantage of the forces’ overstretched positions with devastating lethality. An al Shabaab attack on Kenyan forces at El Adde in January 2016 killed nearly 150 Kenyans. The Kenya government has still not released the identities of many casualties from that day.[71] Al Shabaab forces continue to launch such attacks on outposts, in which multiple suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (SVBIED) breach the base’s defenses and are followed by a rush of infantrymen. The most recent attack on an AMISOM outpost occurred in Kolbio in January 2017.[72]

Al Shabaab has conducted an effective campaign of large-scale attacks inside Mogadishu. It regularly detonates SVBIEDs targeting popular hotels and restaurants frequented by Westerners, Somali politicians, and foreign officials. The hotel and restaurant attacks have become so common that al Shabaab forces have attacked some targets multiple times over the past few years. An attack on Mogadishu’s Dayeh Hotel in January 2017 killed 21 people.[73] The February 19 attack targeting a Mogadishu marketplace killed at least 34 people.[74] Al Shabaab also conducted a series of mortar attacks in Mogadishu intended to disrupt the presidential election process and damage public perception of the federal government’s ability to secure Mogadishu.[75]

Al Shabaab’s destructive presence has not been isolated to Somalia. While the group has planned and conducted attacks throughout much of East Africa,[76] al Shabaab has actively shifted focus onto Kenya. The devastating attacks on the Westgate Mall and Garissa University in 2013 and 2015 are well-documented. Lesser-known al Shabaab operations in Kenya are designed either to shift Kenyan political opinion toward withdrawing forces from Somalia or to recruit Kenyan Muslims to its ranks. Hundreds of Kenyans were among the al Shabaab militants who attacked the Kenyan Defense Forces base at Kolbio in January 2017, including one of the suicide bombers.[77] Along with larger-scale attacks, al Shabaab frequently ambushes buses and tourists along the Somali-Kenyan border. A series of attacks on tourists in the border town of Mandera, Kenya, in October 2016 was meant to reduce support for Kenyan AMISOM deployments.[78] Militants frequently conduct “seize-and-sermon” operations in Kenya, during which the al Shabaab fighters seize a town and indoctrinate locals before security forces arrive.

Al Shabaab efforts to influence the Kenyan political debate over deploying forces in Somalia have been especially effective. Growing numbers of Kenyan officials speak of withdrawing from Somalia and simply focusing on border walls and fences to provide security from the al Shabaab threat. Such an approach will probably not protect Kenya. It will certainly cause the US strategy in Somalia to fail.

Al Shabaab has exploited shifts in the AMISOM force posture to prepare for its counteroffensive. When Ethiopia withdrew troops in late 2016, al Shabaab militants immediately reentered the towns of Burduhule, Rabdhure, Garasweyne, and Tiyeglow in the Bakool region; Eli Ali, Halgan, and Moqokori in the Hiraan region; Bud and Gal’ad in the Galgudud region; and Adan Yabal in the Middle Shabelle region.[79] It consolidated control of these locations by executing those who had cooperated with SNA and AMISOM forces immediately after occupying the towns.[80]

The ease with which al Shabaab flipped the towns shows that it had retained a presence nearby and that other territory could be as susceptible to an al Shabaab reconquest. AMISOM and SNA forces temporarily seized some of the populated centers, including the Barire district in the Lower Shabelle region and Badhadhe, Yontoy, and Bulo-Gadud in the Lower Jubba region, but subsequently withdrew and allowed al Shabaab militants to return. AMISOM lacks the capacity to hold forward bases and therefore repeatedly fails to capitalize on territorial gains.[81]

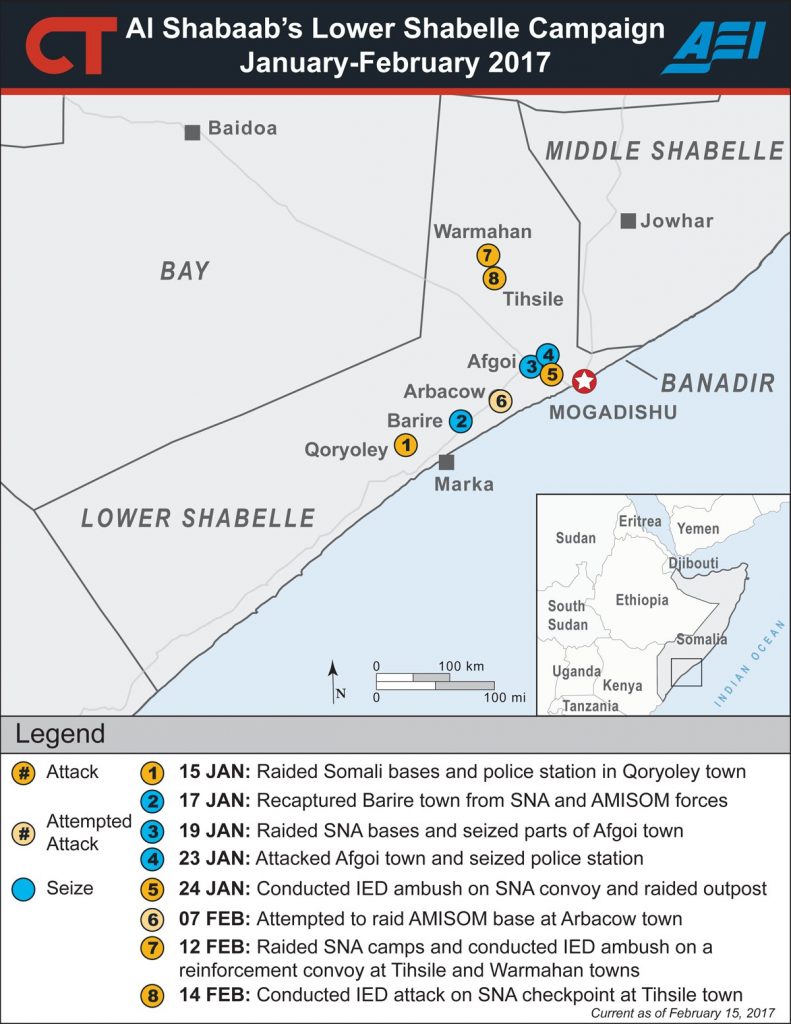

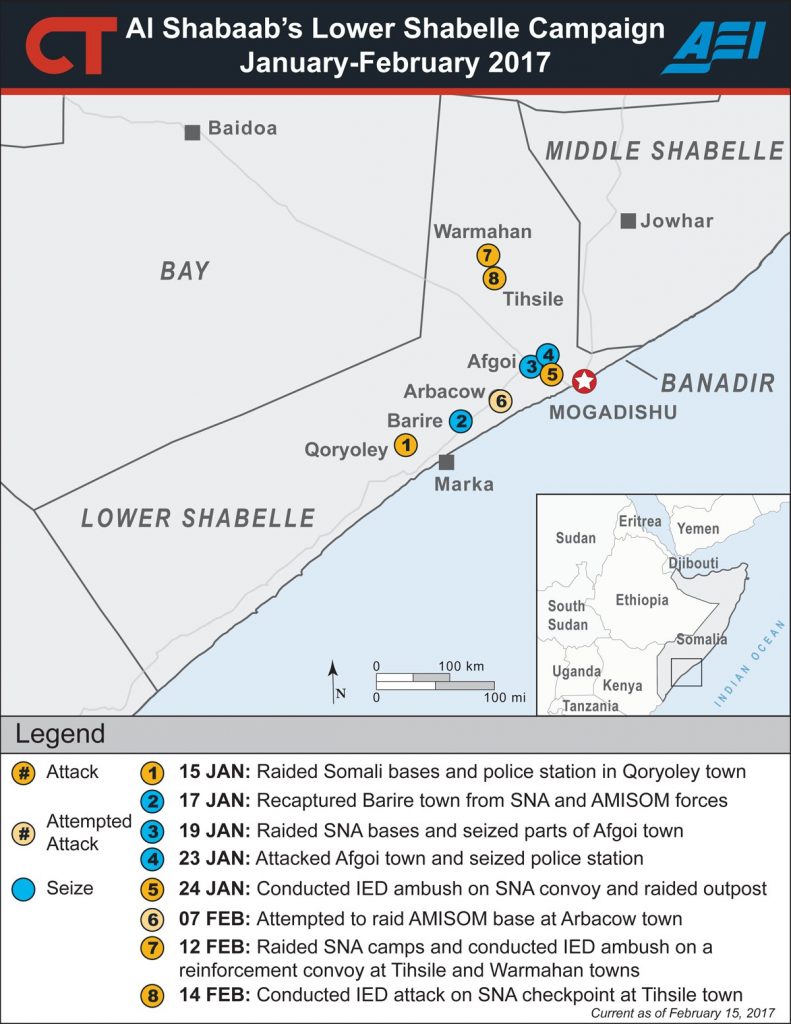

Al Shabaab began 2017 with a push along the Lower Shabelle corridor, the stretch of land connecting Mogadishu to Kismayo, and with targeted attacks against Kenyan troops. The area was one of the last to fall to AMISOM and had been a sanctuary for al Shabaab’s senior leadership. The group focused attacks against AMISOM and SNA positions in Afgoi, a strategic town just southwest of Mogadishu. Al Shabaab launched a multiday assault on Afgoi between January 19 and January 24, during which it seized large parts of the town and ambushed several SNA convoys and checkpoints.[82] It also carried out a string of attacks along the main road in the Middle and Lower Shabelle regions, attacking near Jowhar on January 4, Mahaday on January 6, Afgoi on January 9, Jowhar on January 11 and 12, Mahaday on January 17, and Jowhar and El Baraf on January 18.[83] Al Shabaab also used sophisticated raid and ambush tactics to draw AMISOM forces out of the well-defended Baledogle base and attack them in the open near Afgoi, killing more than 20 SNA soldiers in the process on February 12 and 14.[84] It has thus acquired important positions from which it will be able to carry the fight toward Mogadishu and Kismayo.

Confirmed U.S. Counterterrorism Operations in Somalia

Looking Ahead

Conditions in Somalia are set for al Shabaab to recoup its losses of the past few years. The group has recovered from the major offensives against it in 2011 and 2012. AMISOM remains highly fragmented, and the staying power of the TCC contingents is unclear. Growing instability in East Africa may have ramifications for the ability of regional countries to support the AMISOM mission.

Further, the SNA is not yet able to secure terrain without significant external support. The SFG is attempting to draw regional security forces into the SNA fold, but these forces frequently clash with local militias and with one another.[85] Finally, the SFG will require support as it continues to build its legitimacy inside Somalia.

The US must recognize the risks in Somalia as al Shabaab resurges. The Trump administration has signaled a possibly waning interest in the fight against al Shabaab.[86] However, drawing down American investments in the fight against al Shabaab now would be a mistake. It would likely allow al Shabaab to rebuild its shadow state in Somalia. The US should leverage members of the AMISOM coalition to continue their operations in Somalia and should assist in improving how AMISOM contingents operate on the ground. The Pentagon is pushing for expanded targeting authority against al Shabaab and for reduced restrictions on U.S. support to the SNA that would permit American forces to operate alongside Somali soldiers during operations. The U.S. must recognize that a strategy of attrition and disruption may not be sufficient to neutralize al Shabaab’s threat.[87]

The US must recognize that al Shabaab’s success has come from its ability to hijack local grievances and provide a semblance of stability in a fractured country. It must further recognize that the UN, EU, and African Union are not willing or able to lead or pay for the efforts required to defeat al Shabaab, let alone to stabilize Somalia. Finally, it must recognize above all that American national security interests are directly tied to Somalia’s fate.

Allowing al Shabaab to regain control of a large safe haven in southern Somalia will provide important resources to al Qaeda movements throughout Africa and the Middle East, as well as a base from which to plan and prepare attacks against Europe and the United States. It is time to move past Black Hawk Down and confront the reality that Somalia matters to America.

Al Shabaab's Lower Shabelle Campaign

Al Shabaab's Lower Shabelle Campaign Ethiopian AMISOM Withdrawals

Ethiopian AMISOM Withdrawals Confirmed U.S. Counterterrorism Operations in Somalia

Confirmed U.S. Counterterrorism Operations in Somalia