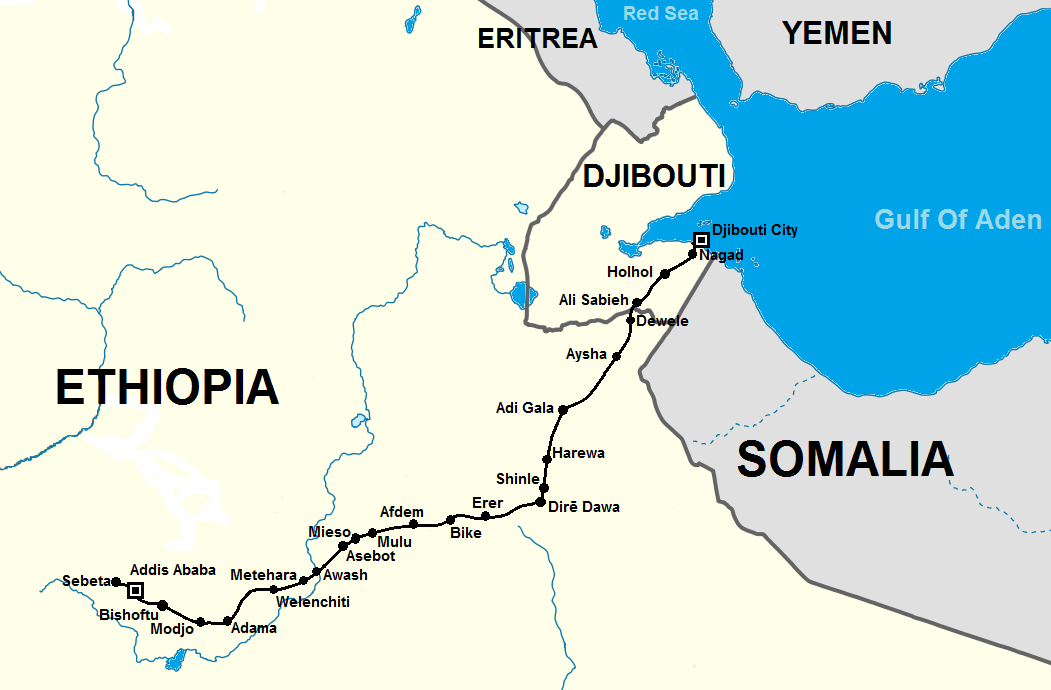

The Chinese-built Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway. (Photo: Skilla1st)

Launched in 2014, One Belt One Road (一带一路), presented internationally as the Belt and Road Initiative, is China’s signature vision for reshaping its global engagements. It is strategic and comprehensive in scope and an essential component of the Communist Party of China’s (CPC’s) twin objectives of achieving national rejuvenation (zhonghua minzu weida fuxing, 中华民族伟大复兴) and restoring China as a Great Power (shi jie qiang go, 世界强国). It now spans three continents and touches 60 percent of the world’s population. The 65 or so countries that have so far signed on to the program (including approximately 20 from Africa) account for 30 percent of the world’s GDP and 75 percent of its energy reserves. Some 50 Chinese state owned companies are implementing 1,700 infrastructure projects around the world worth about $900 billion. One Belt One Road (OBOR) has been written into the state and ruling party constitutions as strategic priorities for China to attain Great Power status by the middle of the 21st century. All of China’s leaders have advanced this quest since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, but the pursuit has accelerated under President Xi Jinping.

Strategic Rationale

The end state of One Belt One Road is the building of a “Community of Common Destiny for Mankind” (人类命运共同体), defined as a new global system of alternative economic, political, and security “interdependencies” with China at the center (zhongguo, 中国). For this reason, Chinese leaders describe One Belt One Road as a national strategy (zhanlüe, 战略), with economic, political, diplomatic, and military elements (综合国力), not a mere series of initiatives.

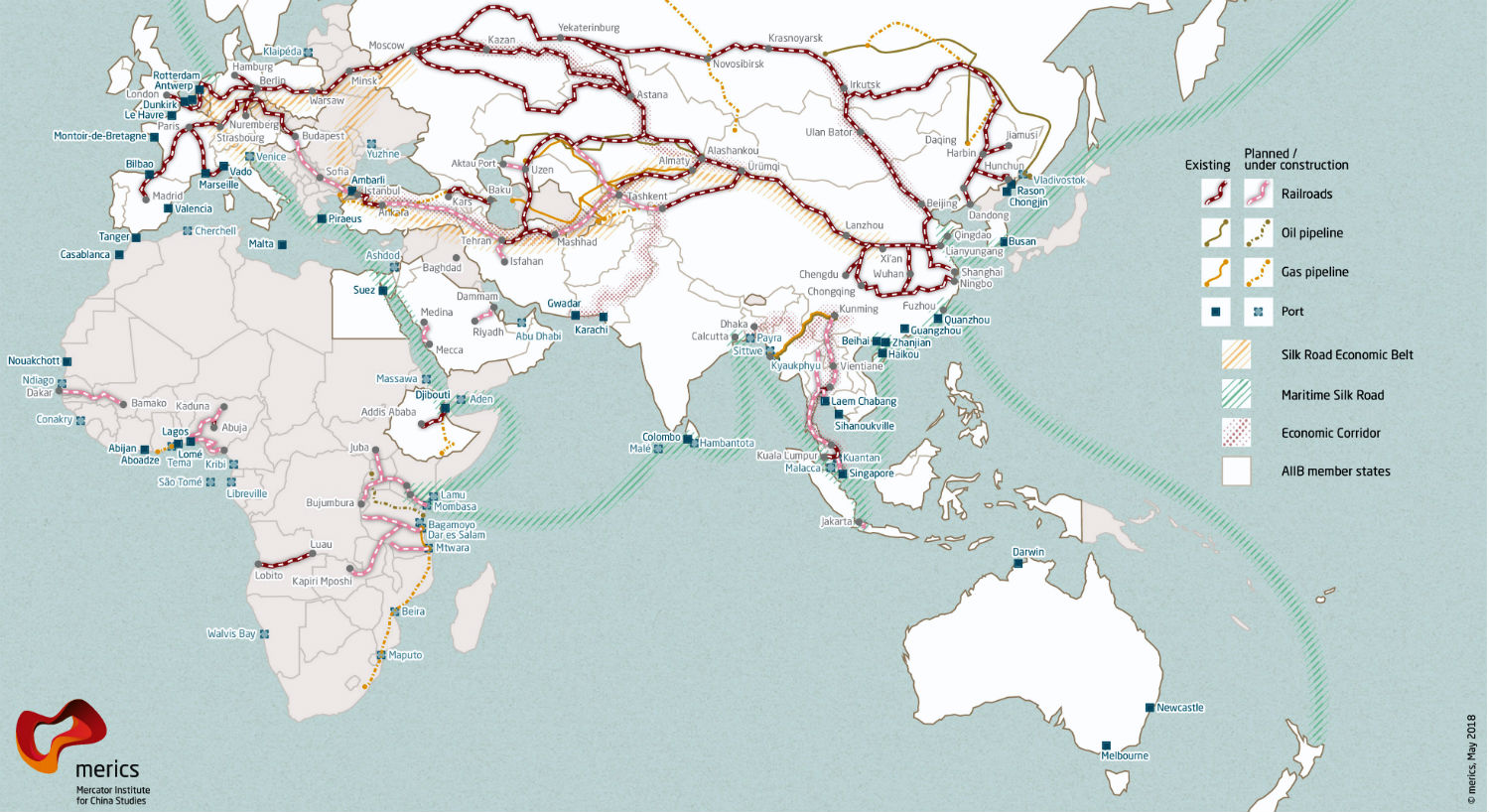

OBOR directly supports many elements of China’s national security strategy. At a macro level, it seeks to reshape the world economic order in ways that are conducive to Beijing’s drive for Great Power status. One Belt One Road has two components. The Silk Road Economic Belt establishes six land corridors connecting China’s interior to Central Asia and Europe. It includes railroads to Europe, oil and gas pipelines from the Caspian Sea to China, and a high-speed train network connecting Southeast Asia to China’s eastern seaboard. The Maritime Silk Road establishes three “blue economic passages” knitted together through a chain of sea ports from the South China Sea to Africa that also direct trade to and from China.

The end state of One Belt One Road is the building of a new global system of alternative economic, political, and security “interdependencies” with China at the center.

One Belt One Road also increases Beijing’s control of critical global supply chains and its ability to redirect the flow of international trade. Central to these efforts are moves to open new sea lines of communication and expand China’s strategic port access around the world. In 2017, Chinese state-owned companies announced plans to buy or secure majority stakes in nine overseas ports, all located in regions where China plans to develop new sea lanes. This is in addition to the 40 ports in Africa, Asia, and Europe in which Chinese state-owned firms hold stakes worth a combined $40 billion.

China’s return on investment from increased port access and supply chains is not all about economics. In five cases—Djibouti, Walvis Bay (Namibia), Gwadar (Pakistan), Hambantota (Sri Lanka), and Piraeus (Greece)—China’s port investments have been followed by regular People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy deployments and strengthened military agreements. In this way, financial investments have been turned into geostrategic returns.

China’s 13th Five Year Plan, a document adopted in 2016 that provides long-range implementing guidance in five-year increments, calls for the “construction of maritime hubs” to safeguard China’s “maritime rights and interests” as it embarks on laying a “foundation for maritime Great Power status” by 2020. The centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, 2049, has been set as the year when it will become the world’s “main maritime power” (海洋强国). Accordingly, China’s drive to acquire port access and secure supply lines are likely to intensify alongside the expansion of the Maritime Silk Road. In 2010, only one-fifth of the world’s 50 largest deep water ports had any Chinese investment. By 2019, it had increased to two-thirds. The China Ocean Shipping Company, which controls most Chinese overseas port holdings, is now the world’s fourth largest shipping fleet. Beijing’s merchant marine has quadrupled since 2009 to become the world’s second largest. It now moves more global cargo that any other country.

Beijing also plans to use the artery of routes envisaged under OBOR to reduce China’s dependence on maritime chokepoints that could be contested by rivals. The PLA is locked in territorial disputes with Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam, South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Brunei, in its so-called “near seas” (jinhai 近海). This raises the risk that they could create a blockade during a crisis that would disrupt its shipping. To counter the threat, One Belt One Road is being positioned to reroute traffic to Chinese-built port clusters in Sudan, Djibouti, Gwadar, Hambantota, Colombo, and Myanmar to bypass narrow chokepoints in the South China Sea.

Chinese President Xi Jinping.

As a party political instrument, OBOR strengthens Xi’s authority at home. It is a central element of “Xi Jinping Thought,” which is inscribed in the state and party constitutions as a guiding philosophy. This further enables Xi to marshal every resource at his disposal to see his signature program through.

Funding for One Belt One Road comes from “policy lenders” (政策性银行), so called because their lending decisions are responsive to presidential and geostrategic preferences. They include the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank), which have committed over $1 trillion. The Silk Road Fund holds $40 billion in investment funds and is supervised by China’s Central Bank. The Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, whose remit now includes Africa, has a capital base of $100 billion. Additional funds come from China’s foreign exchange reserves and its sovereign wealth fund, which hold $7 trillion and $220 billion, respectively.

To be sure, OBOR faces many problems. First, debates on Chinese social media tools such as Weibo and Renren suggest that it does not enjoy broad domestic support. Second, concerns are growing about economic sustainability in the countries where massive Chinese-funded infrastructure projects are being implemented, as their governments take on more debt to pay for them. Third, hostility is rising in many countries toward policies that favor Chinese workers over locals in construction and infrastructure contracts. This has been most prominent in African countries, such as Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia, to name a few. Fourth, some of Beijing’s rivals in Asia and around the world are increasingly uneasy about what they see as an effort to use OBOR to expand China’s military posture and political leverage.

How Does Africa Fit into the Belt and Road?

The revival of trade routes along China’s ancient Silk Road linking China to East Africa is being promoted by Chinese leaders as a symbol of China’s commitment to Africa. According to Xi, Africa stands to benefit from OBOR because “inadequate infrastructure is the biggest bottleneck to Africa’s development,” a view that is shared by many African leaders. Advocates of One Belt One Road also point to the potential for spinoffs, such as increased private Chinese investments in tourism, real estate, and agriculture, alongside infrastructure projects. OBOR is also increasingly seen as a catalyst for African regional economic integration and competitiveness. A study funded by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa found that East Africa’s exports could increase by as much as $192 million annually if new OBOR projects are used profitably.

As the early focus of One Belt One Road, East Africa has developed into a central node in the Maritime Silk Road, connected by planned and finished ports, pipelines, railways, and power plants built and funded by Chinese companies and lenders. A standard gauge railway connecting Mombasa to Nairobi—the biggest investment in Kenya since its independence—is a flagship OBOR project in East Africa. The electric railway from Addis Ababa to Djibouti, where China established its first overseas naval base and has stakes in a strategic deep water port, is another. From Djibouti, the Maritime Silk Road connects planned and completed Chinese port clusters in Sudan, Mauritania, Senegal, Ghana, Nigeria, Gambia, Guinea, São Tomé and Príncipe, Cameroon, Angola, and Namibia. Another route links Djibouti to Gwadar, Hambantota, Colombo, Myanmar, and Hong Kong. The final arc of this corridor connects Walvis Bay to Chinese port clusters in Mozambique, Tanzania, and Kenya before also connecting to Gwadar.

The One Belt One Road network. (Map courtesy of the Mercator Institute for China Studies)

These revived trade routes help China diversify its supply chains and create a China–Indian Ocean–Africa–Mediterranean Sea Blue Economic Passage to connect Africa to new maritime corridors in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar. Beijing’s military posture matches its expanding maritime and naval reach under OBOR. This is particularly evident in the Indian Ocean, where China’s planned sea lanes are heavily concentrated and its rivalry with India is growing. Africa’s importance to China in this regard stems from its location in a maritime area in which Beijing hopes to expand its presence and power projection. Indeed, a decade ago China’s reach in Africa’s adjacent waters was nonexistent. Today, it is estimated that the PLA Navy maintains five battleships and several submarines on continuous rotation in the Indian Ocean. This is set to increase in the coming decades as India ramps up its own presence in the area.

China’s antipiracy contingents in Africa, its first deployments outside Asia, have also grown in scope and sophistication since their debut in 2009. They now feature newer classes of guided missile frigates, advanced destroyers, and Special Forces whose roles have evolved to include joint combat drills and patrols, military diplomacy, and increased naval and maritime cooperation and training. Senior Chinese military analysts note that the PLA’s participation in international anti-piracy missions in African seas has strengthened the capabilities China projects it will need to support OBOR. These include basing and expeditionary operations, sea lane protection, and citizen evacuation. All these tasks are in line with what the PLA calls “historic missions” (历史使命) outside its maritime periphery.

Map of the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway. (Photo: Skilla1st)

Africa is also an important end user of China’s industrial overcapacities, particularly coal, cement, steel, glass, solar, shipbuilding, and aluminum, for use in One Belt One Road projects. In Kenya, imports of Chinese cement increased tenfold in 2016 while the Nairobi-Mombasa railway was being built. In 2018, Chinese exports of steel to Nigeria rose 15 percent, and Algeria tripled its imports of the product. In 2019, China’s global aluminum exports rose by 20 percent, with exports to Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa reaching about $46 billion.

The offloading of Chinese excess capacity in Africa has not been without problems. In East Africa, Kenya has been the hardest hit. In 2017, Kenya’s cement exports to the region dropped by 40 percent due to the flood of Chinese cement entering the country. That year, the World Bank warned that Kenya’s economic competitiveness was declining due to the influx of Chinese excess capacity in Tanzania and Uganda, its main export destinations. In the past decade, Tanzania and Uganda’s imports from China increased by as much as 60 percent, while those from Kenya grew by 4 and 6 percent, respectively, over the same time period. Kenyan manufacturers have blamed their country’s declining market share of industrial products on Chinese firms, which they also accuse of importing raw materials from China and hiring Chinese labor.

Implications for Africa

China’s policy of employing Chinese labor for its infrastructure projects in Africa has resulted in more than 200,000 Chinese citizens working on OBOR contracts across Africa. This, in turn, creates a justification for Beijing to take a hands-on approach toward protecting them, as well as its sprawling investments. The Academy of Military Science, China’s top military research institute, said in its latest strategic review that One Belt One Road has increased the need for a globally focused strategy to protect China’s overseas interests. Similarly the Communist Party of China has adopted the concept of “protecting overseas nationals” (haiwai gongmin baohu, 海外公民保护) as a core Chinese interest.

Given the strategic nature of Chinese investments in Africa, such as ports, railways, oil and gas pipelines, and power plants, some African governments view attacks on Chinese interests as a threat to their own national security. Signed by African leaders in 2018, the current China-Africa Action Plan, states that the security of “major domestic economic projects” and “safety of Chinese nationals, Chinese companies, and major projects” will be prioritized in intelligence, military, and police cooperation. That year, Uganda became the first African country to deploy its military to protect Chinese interests in response to attacks on Chinese nationals by locals. In neighboring Kenya, China’s security services set up and trained an elite Kenyan police division to protect the Mombasa-Nairobi railway.

Workers at the Port of Mombasa, Kenya. (Photo: Make it Kenya/Stuart Price)

In its attempt to neutralize threats to its investments, Beijing has also provided technologies to build local capacity for intelligence collection, surveillance, monitoring, and response. This includes facial recognition technologies, which were recently supplied to Angola, Ethiopia, and Zimbabwe. This is causing apprehension in Africa, given the tendency for some governments to use intrusive technologies against political opponents and activists.

Concerns are also being raised about the role of private Chinese companies in Africa’s security sectors Under Chinese law, the line between public and private companies is blurred. Private firms are required to install ruling party branches within their decision-making structure, a regulation known as guojin mintui (国进民退). This relationship is tightened by the practice of strictly hiring demobilized PLA soldiers and former Special Forces, intelligence, and police officials. Today, around 3,000 ex-military members are employed in One Belt One Road projects around the world.

Chinese private security firms like DeWe Security and Frontier Services Group are also increasingly present in places like Angola, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Sudan, South Sudan, Zimbabwe, and more recently, Somalia. Chinese private security contractors mostly work discreetly with local police, intelligence, and military personnel to secure Chinese interests and provide advice and strategy on when and how force should be used. However, in some instances they have been more overt, such as in the rescue of 29 Chinese hostages in Sudan’s Kordofan State in 2012. In another instance, ex-PLA soldiers hired by DeWe evacuated 300 Chinese oil workers caught in a shoot-out between rival militias in the South Sudanese capital Juba in 2016.

East African countries owe China about $29 billion in loans for infrastructure, energy, and construction projects.

One Belt One Road has troubling implications for debt sustainability. According to the Johns Hopkins China Africa Research Initiative, East African countries owe China about $29 billion in loans for infrastructure, energy, and construction projects. Beijing appears in some cases to have attached more importance to acquiring strategic assets than debt repayment from its partners. In 2017, Sri Lanka handed over Hambantota port to Chinese state-owned companies on a 99-year lease after defaulting on an infrastructure loan. Pakistan handed over Gwadar port on a 40-year lease in an arrangement where the Chinese partner also retained 90 percent of its revenues.

These developments set off alarm bells in East Africa, where speculation is rife that Djibouti and Kenya, both highly indebted to China, could lose their ports in a similar fashion. In January 2019, Uganda’s auditor general warned of the country’s ballooning debt and the risk that conditions placed on its loans were a threat to its sovereign assets. The following month, the Kenyan parliament opened a probe into the circumstances under which the strategic Indian Ocean port of Mombasa was used as collateral for the loan the government secured from China’s Exim Bank to build the Mombasa-Nairobi railway.

How Can African Interests Be Protected?

In Africa, debates about One Belt One Road have focused on whether it can support the continent’s infrastructure needs. The World Bank estimates that Africa will need up to $170 billion in investment a year for 10 years to meet its infrastructure requirements. The African Development Bank has posited that if Africa positions itself well, it can source some of this from the OBOR and channel it to the African Union’s infrastructure master plan.

Namibia’s Chinese-built TransNamib Class SDD6 no. 0004. (Photo: Wynand Vermeulen)

Can African countries seize these opportunities and mitigate some of the risks inherent in Beijing’s latest strategy? Accountability and transparency will be the key to answering that question. The opaque nature of many OBOR negotiations prevents public and private sector scrutiny. Parliaments, public protectors, and other oversight bodies must actively monitor such negotiations, create safeguards, and keep the public informed. Beijing is sensitive to how host nations perceive it. When the public is aware, vigilant, and active, OBOR negotiators can become more responsive to local demands. The lessons of Hambantota and Gwadar suggest that when accountability and oversight are absent, the risks of unfavorable agreements, and ultimately default, increase.

One Belt One Road can have positive net benefits for African countries, but much will depend on whether the China-Africa relationship can be placed on more equal footing. It is first and foremost a Chinese geopolitical project designed to advance China’s grand strategy. The challenge for Africa is in establishing where its interests converge with China’s, where they diverge, and how areas of convergence can be shaped to advance African development priorities.

Additional Resources

- Joel Wuthnow, “China’s Belt and Road: One Initiative, Three Strategies,” Strategic Asia, National Bureau of Asian Research, February 4, 2019.

- Paul Nantulya, “Chinese Hard Power Supports Its Growing Strategic Interests in Africa,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 17, 2019.

- Cao Desheng, “Xi’s Discourses on Mankind’s Shared Future Published,” China Daily, October 15, 2018.

- Thomas S. Eder, “Mapping the Belt and Road Initiative: This Is Where We Stand,”Mercator Institute for China Studies, July 6, 2018.

- Joel Wuthnow, “Chinese Perspectives on the Belt and Road Initiative: Strategic Rationales, Risks, and Implications,” China Strategic Perspectives No. 12, Institute for National Strategic Studies, September 27, 2017.

- Xi Jinping, 习近平:加强合作推动全球治理体系变革 共同促进人类和平与发展崇高事业 (“Strengthen Cooperation for Advancing the Transformation of the Global Governance System and Jointly Promote the Lofty Task of Peace and Development for Mankind”), published by Xinhua, September 28, 2016.

- Christopher D. Yung, Ross Rustici, Scott Devary, and Kenny Lin, “Not an Idea We Have to Shun: Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements in the 21st Century,” China Strategic Perspectives No. 7, Institute for National Strategic Studies, October 2014.

- Zhang Lihua, “China’s Traditional Cultural Values and National Identity,” Window into China, Carnegie Tsinghua Center for Global Policy, November 21, 2013.