The Bab el-Mandeb Strait (“Gate of Tears” in Arabic) forms a vital strategic link in the maritime trade route between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean via the Red Sea and the Suez Canal.[1] On one side of the narrow strait lies the Arabian Peninsula. On the other is the Horn of Africa,[2] a fragile region that has been plagued for decades by high levels of violence and instability within and across borders,[3] and which in recent years has served as a launching pad for terrorism, piracy, human trafficking, and smuggling operations.

In a 2013 essay for the Rift Valley Review, Christopher Clapham described the history of the Horn of Africa as “peculiarly violent” and consisting “overwhelmingly of tragic human suffering.”[4] Lately, however, there have been signs that a brighter future for this volatile region might not be beyond reach. This is thanks in part to the bold leadership of Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, whose whirlwind diplomacy yielded a peace deal with Eritrea and an easing of regional tensions that earned him the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize.[5]

Nevertheless, many local and regional challenges remain unresolved. Meanwhile, the Horn of Africa has fast become an arena in which Middle Eastern states are vying with each other to advance their commercial and geopolitical interests in the broader context of intensifying U.S.-China strategic rivalry. Indeed, China’s activities in and around the Red Sea are coming under increased scrutiny. Whether and how these intra-Gulf and great power rivalries persist will go a long way to determining whether the Bab el-Mandeb becomes a gateway to stability and shared prosperity or to tears.

The intrusion of intra-Gulf rivalries

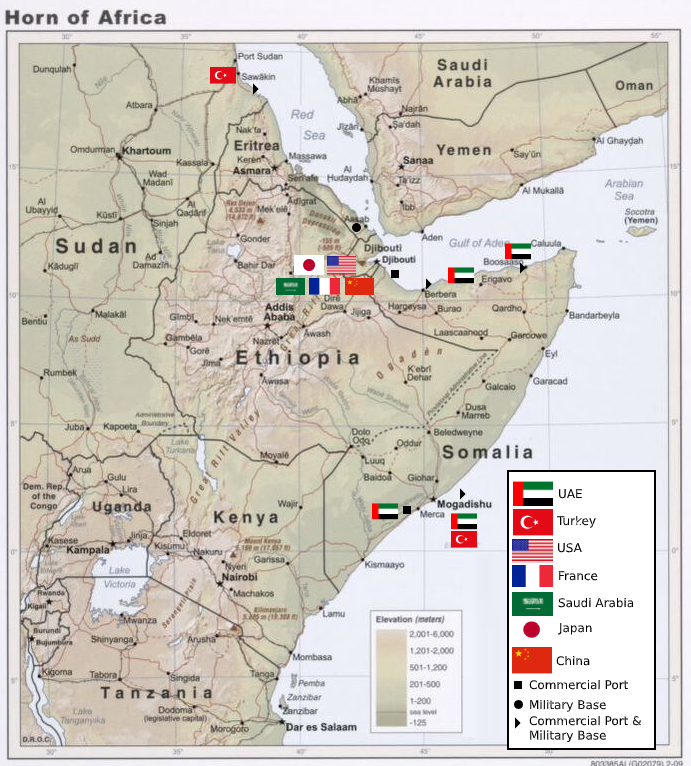

The Horn of Africa has entered a period marked not only by potential transformational change but also by heightened interregional activity. Propelled by economic interests and geopolitical considerations, the Gulf Arab countries (Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar, in particular) as well as Turkey and Egypt have become increasingly prominent external actors in the Horn of Africa and the surrounding maritime space.

The Horn of Africa is a trade and investment gateway to a continent brimming with economic potential that has drawn the attention of traditional partners and new entrants. The Gulf states have moved quickly to position themselves to capitalize on the expected boom[6] in the real estate, infrastructure, and construction sectors; and to exploit the Horn’s potential as a breadbasket for food production and agriculture. Dubai Ports (DP) World has acquired a strategic foothold by securing concessions to operate container and cargo ports in Djibouti (Doraleh), Eritrea (Assab), Somalia (Kismayu), and Somaliland (Berbera).[7] Between 2000 and 2017 the Gulf states invested $13 billion in the Horn of Africa (mainly in Sudan and Ethiopia) and disbursed $6.6 billion in overseas development assistance.[8] Since then, Gulf money has continued to flow liberally into the Horn.[9]

Geopolitical considerations, and not just potential economic gains, have propelled Gulf Arab engagement in the Horn of Africa. Over the past decade, the Gulf states have come to regard the region “as an integral part of their core security perimeter.”[10] The initial stimulus was an upsurge in piracy and maritime crime.[11] Gulf Arab concerns about the possible spillover of the Arab Spring uprisings, the rise of ISIS, Iran’s heightened activity in the region, and the conflict in Yemen — as well as the perceived vacillation of U.S. policy and decline of American primacy — elevated further the strategic importance of the Horn. In response, the Gulf states have adopted foreign policies that are markedly more independent and assertive than in the past, that have a wider geographic ambit, and that seek to shape rather than merely react to events.[12]

Two overlapping rivalries have driven and defined this proactive engagement: competition between Saudi Arabia and Iran; and a contest pitting Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt against Qatar and Turkey. These rivalries have manifested in a series of interlinked proxy conflicts waged across the Middle East. They have also rippled through the Horn of Africa, as the dueling protagonists vie with each other for ports, military bases, and political allies. Political and military actors in the Horn have seized on these rivalries to advance their own goals.[13]

Although the fast-paced positive changes in the Horn over the past two years have been primarily locally driven, the Gulf states have used checkbook diplomacy strategically and effectively.[14] Saudi-Emirati diplomacy backed by pledges of economic assistance has had a salutary effect on the Horn; for example, in brokering the Eritrea-Ethiopia peace agreement in July 2018[15] and in facilitating dialogue between Eritrea and Djibouti.[16] Qatar, too, has engaged in mediation efforts, in Darfur, Eritrea, and Djibouti.[17]

Nevertheless, Gulf diplomatic engagement in the Horn has been colored by intra-Gulf rivalry and has largely taken the form of zero-sum competition. Eritrea, Somalia, and Sudan all have troops fighting alongside Saudi Arabia in Yemen. Thus it is no surprise that Saudi Arabia and the UAE rushed aid to shore up the Transitional Military Council in Sudan following the removal of President Omar al-Bashir from office,[18] or that Saudi Arabia pledged aid to Somalia the very day the latter cut ties with Iran.[19] When Djibouti, Eritrea, and Somaliland declared support for the Saudi camp, Qatar withdrew its observers from the Eritrea-Djibouti border. When Somalia’s federal government sought to remain neutral in the intra-Gulf dispute, the UAE and Saudi Arabia slashed budgetary support. Members of the two opposing camps have courted federal states (regions) in Somalia,[20] compromising the state-building process. They have supported non-state actors in Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea, and Ethiopia[21] — actions that run the risk of exacerbating preexisting local and regional tensions. They have developed integrated commercial and security strategies for the region, designed to ensure a leading role at the point where the east-west trade route enters the Red Sea.[22] Thus intra-Gulf rivalry has featured in the proliferation of foreign military bases and buildup of naval forces in the Horn and the Red Sea.[23]

China’s Belt and Road challenges in the Horn

The intrusion of intra-Gulf rivalries into the Horn of Africa is taking place against a backdrop of great power competition — and not for the first time in the region’s modern history. In the late 1970s, for example, the Horn was a Cold War arena of opportunistic alliances and counter-alliances as well as state-sponsored subversive activities.[24] In the current period, China’s commercial and military inroads into the Horn can be seen in the context of the country’s expanding global power and influence, and U.S. efforts to counter it.

Djibouti and Ethiopia are the primary focal points of Chinese engagement in the Horn. In both cases, Chinese economic activities are concentrated in four major sectors: roads, rail, energy, and communications. China has meshed its global maritime ambitions with Djibouti’s agenda to transform itself into a commercial trade hub for the Horn of Africa region.[25] China Merchants Port (CM Port) has played a key role in these efforts. As a joint-venture partner with the Djibouti Ports and Free Zones Authority in Port de Djibouti Société Anonyme, in which CM Port holds a 23.5 percent stake,[26] it has developed Doraleh Multipurpose Port (DMP) and the Djibouti International Free Trade Zone.[27] More recently, Djibouti and Ethiopia signed a deal to transport Ethiopian natural gas to an export terminal to be located in Damerjog on the Red Sea, building on a $4 billion investment pledge by China’s POLY-GCL Petroleum.[28]

In the case of Ethiopia, as in that of Djibouti, China has aligned itself with the ambitions of the government in place, developing close ties with the self-styled “developmental regime” of Hailemariam Desalegn and now with the Abiy administration.[29] During that time, Ethiopia has emerged as China’s second-largest African borrower and a major Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) partner. Ethiopia has also become a valuable regional platform for China — home to the $200 million Chinese-funded African Union Conference Center and Office Complex, as well as to the representational offices of the Chinese Commerce Ministry and the China-Africa Development Fund, and the regional headquarters of Xinhua News Agency.

Chinese-backed infrastructure projects intended to boost regional connectivity, in accordance with the BRI, include the Ethiopia-Djibouti Railway and the Ethiopia-Djibouti Water Pipeline. The railway project, in particular, bears all the hallmarks of the BRI — a large-scale cross-border infrastructure project financed through a concessional loan, undertaken by Chinese contractors, and aimed at linking potential production sites to a trade hub. Elsewhere in Ethiopia, Chinese firms have built and funded the $475 million Addis Ababa Light Rapid Transit network, the $86 million ring road, the country’s first six-lane highway, and the Addis Ababa Bole International Airport terminal expansion.[30] [31] This past December, Ethiopia’s first observatory satellite — three-quarters of the cost of which was paid by China — was launched from Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center in Shanxi Province carried aboard a Long March 4B rocket.[32]

However, it is important to mention that China’s economic engagement in the Horn has not been all smooth sailing. In the scramble for port and cargo facilities, CM Port has been jockeying for advantage with DP World, with the two global port operators at the center of legal disputes over Doraleh Container Terminal[33] and DMP. Regarding the former, Djibouti unilaterally terminated the contract with DP World, nationalized the container terminal, and transferred the concession to CM Port.[34] After the termination of DP World’s concession, CM Port began an expansion of the port facilities, which, when completed, will provide Chinese-flagged vessels with priority handling and lower docking fees.[35] Regarding the latter, Djibouti granted the right to develop DMP to CM Port without first having offered the opportunity to DP World, which subsequently filed suit against China Merchants to enforce its legal claims.[36] It remains to be seen, therefore, whether China’s BRI projects in the Horn and elsewhere in East Africa will bolster its relations with the UAE and other Gulf actors or serve as an irritant.

Meanwhile, China’s lending practices in the Horn, as elsewhere, have come under increasing scrutiny. Two-thirds of Djibouti’s external debts are owed to China,[37] prompting speculation that the government might expropriate or transfer foreign-owned properties to pay out the loans granted by the Export-Import Bank of China to Djibouti for infrastructure development.[38] According to the IMF, although large-scale infrastructure investments and rapid expansion of trade and logistics activities have spurred strong growth, they have placed the country “in high risk of debt distress.”[39]

China’s lending practices in the Horn, somewhat predictably, have drawn sharp criticism from American and European officials.[40] Loan repayment issues have also prompted self-reflection by Chinese officials regarding the inadequacy of project planning and risk management.[41] A Chinese diplomat told the Financial Times in June 2018 that China is “way overextended” in Ethiopia.[42] State export credit insurer China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation (Sinosure) was forced to write off more than $1 billion in losses on the Ethiopia-Djibouti rail link. China extended a $1 billion loan to finance the building of transmission lines[43] and China Gezhouba Group Company was contracted to accelerate work to complete construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), a project that has been complicated by the ongoing dispute between Ethiopia and Egypt over water share.

In addition, there are serious questions about the profitability of some of the projects in which China has been involved.[44] Since it began operation in January 2018, the Addis Ababa-Djibouti standard-gauge railway has had to contend with electricity shortages and lower-than-anticipated freight volumes.[45] The failure of the project to generate the expected revenue led to the renegotiation of billions of dollars in Chinese commercial loans[46] and later to China’s cancellation of all of Ethiopia’s interest-free loans.[47] China has faced this pushback not just in Djibouti and Ethiopia but elsewhere in East Africa, notably Tanzania and Kenya.[48]

Finally, and importantly, the establishment in 2017 of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Support Base in Djibouti has sounded alarm bells in Washington.[49] As some experts have written, the base reflects the “far seas protection” aspect of China’s new naval doctrine.[50] In anticipation of the completion of the facility, U.S. Ambassador to Djibouti Tom Kelly remarked that managing American and Chinese forces in close proximity “will be a challenge for all involved.”[51] Later, USAFRICOM’s commander, Gen. Thomas Waldhauser, told Congress that Djibouti’s increasing partnership with China “encroaches on and, at times, diminishes U.S. access and influence.”[52] Leading a delegation to Djibouti in February 2019, U.S. Senator Jim Inhofe commented, “We can’t afford to deny China’s encroachment in a vital port any longer.”[53] The establishment of the base, therefore, has fueled concerns about China’s growing military power and its expanded global posture, spurring the Pentagon to develop a strategy to address them.

Gateway to shared stability and prosperity or Gate of Tears?

There have been clear signs of progress toward stability in the Horn of Africa in recent years. However, a multitude of challenges remain, including the unresolved Somalia-Kenya maritime border dispute; ethnic tensions and rival nationalisms in Ethiopia; armed conflict between Somaliland and Puntland, partly due competing claims to ownership of the oil-rich Sool/Sanaag region; and simmering tension over the GERD.[54]

The financial flows from and flurry of peace-making efforts by the Gulf states have been welcome contributions to stability in the Horn. Likewise, Chinese financing and building activity have improved connectivity and logistics, boosting the prospects for economic growth. Yet, at the same time, the intrusion of intra-Gulf rivalries and U.S.-China strategic competition into the Horn places these and other potential gains at risk.

It would be misguided to view all aspects of Chinese engagement in the Horn in zero-sum terms through an adversarial lens, or to see Chinese economic and/or security interaction with the countries of the region as uniquely or exclusively negative. Far from boldly challenging American supremacy in the Horn, China is capitalizing on the sporadic interest and narrow security focus of U.S. policy in the region, as well as on African frustration and fatigue with traditional Western donors and partners. Djibouti turned to China for investment after being unable to secure it from the U.S. and other Western sources.[55] In Ethiopia, China responded to overtures from a partner determined to build a robust relationship aimed at driving its industrial development strategy.[56]

To be sure, aspects of China’s engagement in the Horn — such as some of its lending practices and the upgrading of the PLA Support Base — warrant concern, vigilance, and imaginative policy responses. The “U.S. Strategy for Africa” signed into law by President Donald Trump in December 2018 would seem to be a promising step in the right direction, in that it aims to advance trade and commercial ties with key African states, prioritizes foreign assistance, and seeks to maintain the U.S. as the preferred security partner in Africa.[57]

However, for this strategy to be shaped and applied in the Horn of Africa in a manner that boosts the prospects for peace, stability, and development requires more than just bold proclamations. What is needed is concrete action, a generous allocation of resources, a renewed emphasis on multilateral cooperation, a firm commitment to help temper rather than turn a blind eye to or further inflame intra-Gulf rivalries, and a willingness to explore opportunities to work together with China.

*Dr. John Calabrese teaches US foreign policy at American University in Washington, DC. He also serves as a Scholar in Residence at the Middle East Institute where he is directing MEI's project on The Middle East and Asia (MAP). The views expressed in this article are his own.

Photo by YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP via Getty Images