Debating Ideas aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It offers debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

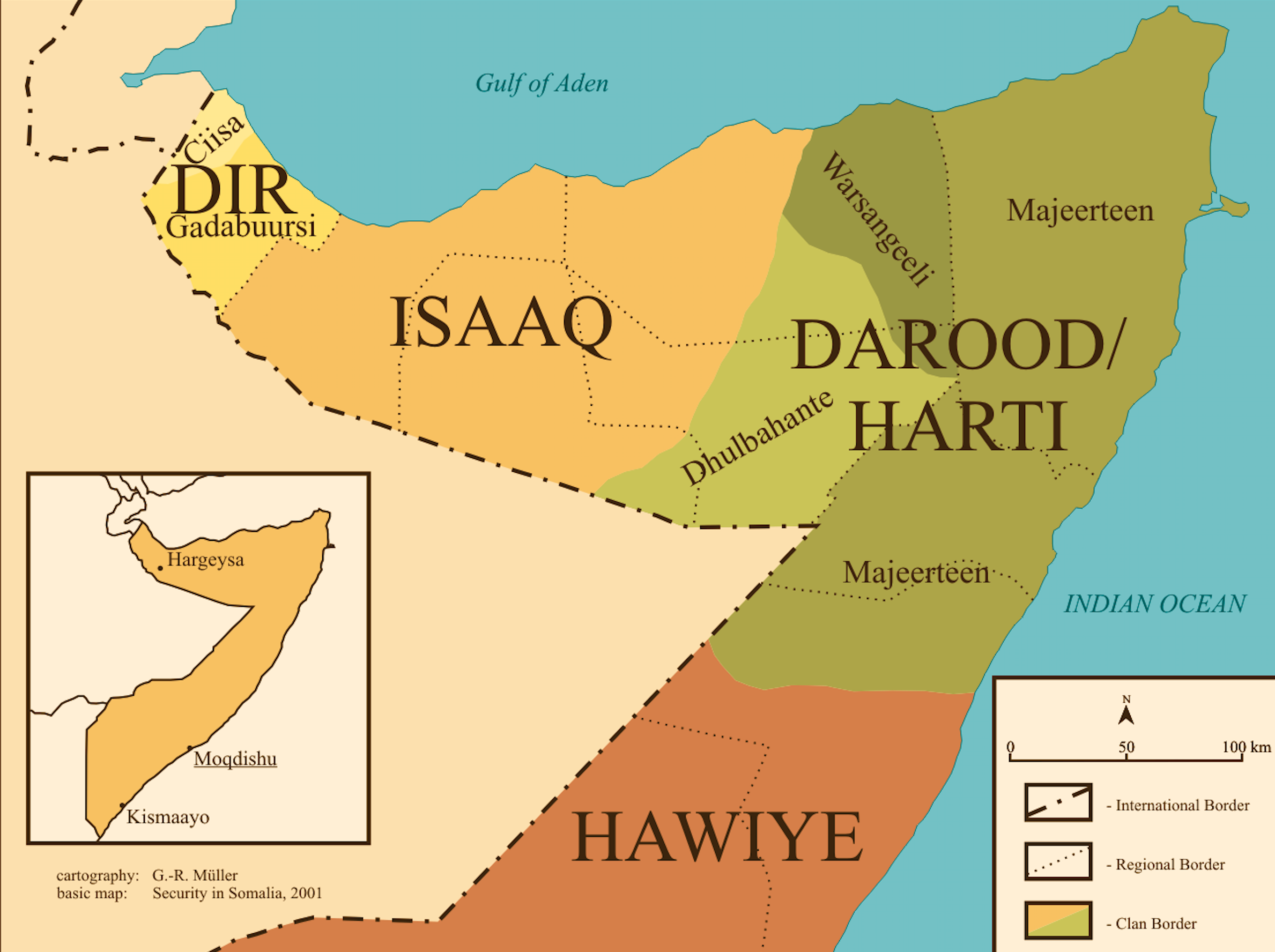

Border dispute areas Lasanod, Somaliland. Produced by the Max Plank Institute. Copyright Markus Hoehn

. Summary

At the end of December 2022, a young politician was assassinated in Lasanod. This was the most recent targeted killing in a long series of similar attacks, which had not been prevented or at least followed up and solved by the Somaliland authorities in town. In reaction, Lasanod residents started protesting against the prevailing insecurity in town. This escalated into violence when Somaliland troops controlling the place started shooting at protesters, killing some 15 persons and injuring more (mainly youngsters). The Somaliland forces eventually retreated from Lasanod in early January 2023 leaving the place self-administered. A committee was formed to discuss the future of the town. Meanwhile, the Somaliland government is amassing military forces and equipment in the surroundings of Lasanod. As of early February, it is unclear what will happen. Yet, there is a possibility that the situation will escalate into major armed conflict resulting in massive human rights violations and political implications for the whole region. If Somaliland loses Lasanod, its political claim must be readjusted. International actors and anyone interested in peace in the Horn of Africa must urgently pay attention to this seemingly “local” conflict, which, however, touches upon much more far-ranging political issues. The question is: what solution to this problem can be found that does not include armed conflict and potentially ethnic/clan-cleansing?

. Assassinations and rumours

On Monday 26 December 2022, Abdifatah Abdullahi Abdi “Hadrawi”, a young party official of Somaliland’s largest opposition party Wadaani, who hails from the Dhulbahante clan dominant in the area, was assassinated in Lasanod. There has been a long series of similar assassinations of mostly Dhulbahante intellectuals and officials, often those working for the Somaliland administration that had forcibly taken over the city at the end of 2007. The assassinations began in late 2009 and continued over many years.[1] They were discontinued for some time between 2012 and 2015. In some cases, culprits were captured. Yet, the assassinations started again in 2018.[2] Over the past two years, some seven people were killed. In total, at least 40 persons fell victim to these targeted killings. Muse Bihi, President of Somaliland, recently claimed that 32 suspects related to these cases were in custody. Yet, the public in Lasanod is of a different opinion. Many stressed that the Somaliland administration had not pursued these assassinations effectively and the killers were not captured.

Three rumours about the assassinations in Lasanod stand out: first, that the killings are part of intra-Dhulbahante feuds. Yet, this seems rather improbable. Over the years, many feuds between Dhulbahante sub-clans happened, yet in those cases, everybody knew who was involved; even the killers were known. Second, that Al Shabaab are behind these killings to create insecurity in an already volatile place. This is a rumour, yet it is not implausible. In 2008, Al Shabaab attacked Somaliland with massive bombings in Hargeysa. The group rejects the independence of Somaliland. So far, it was their strategy (also in south-central Somalia) to induce unrest in an already volatile place to increase their relevance. What remains puzzling is why Al Shabaab should be clandestinely killing people for so long (over 14 years); normally, they would create unrest and then take control more quickly. The third rumour in town is that the administration in Hargeysa and its representatives in Lasanod are behind the targeted killings. The logic behind this, which is admittedly not straight-forward, is that Isaaq elites in Somaliland do not want the Dhulbahante to integrate. They want to keep power and government to themselves but need the Dhulbahante territory to underline their claim to independent statehood. Moreover, some would add that the assassinations of prominent Dhulbahante are a form of late revenge of “Isaaq” against Dhulbahante, as the latter historically supported the Somali dictatorship against the Isaaq guerillas until 1991. Another conspiracy theory, that is not mentioned in Lasanod, but a regional specialist mentioned in oral debate, concerned Ethiopia and its interests in keeping Somali polities weak. Given that Somaliland has gained stability and economic strength and since 2015 has become an important partner of Ethiopia related to the Berbera corridor (importing and exporting goods to/from Ethiopia via the harbour of Berbera in Somaliland), creating insecurity in Lasanod could be a strategy by the government in Addis Ababa to weaken Somaliland. Ethiopia could have used paid assassins.

What is certain is that the lack of clarity and absence of information around who was driving the assignation campaigns induced insecurity in the area, creating tensions between residents of Lasanod and the Somaliland administration.

. The Reactions: upheaval in town

The feeling of insecurity and the frustration of many town dwellers with some Somaliland officials (Isaaq by clan) including the governor of the Sool region motivated locals to stage demonstrations in late December 2022, triggered by the most recent assassination of Abdifatah “Hadraawi”. Demonstrations continued for several days. The situation became chaotic when youngsters were throwing stones at Somaliland forces deployed to control the town. On several occasions, the soldiers opened fire, killing 10-15 people and injuring many more (mostly young men and women).[3] On Wednesday 3 January 2023, a local trader was shot by Somaliland forces patrolling the town; he was armed to guard his business and in the context of disarming him, he was killed. This provoked considerable outrage among his close relatives, who took to arms and attacked the Somaliland army in town, which one day later, on 4 January, withdrew to positions outside of Lasanod to prevent further bloodshed.

In reaction, many locals started celebrating their “freedom” from Somaliland’s “occupation” and began waving the “blue flag” of Somalia in town (and on social media) to demonstrate their support for a united Somalia against the secession that formed the Republic of Somaliland (unilaterally declared in 1991). This provoked angry political reactions by Somaliland authorities, who reiterated that Lasanod is part of Somaliland.

. The pretext

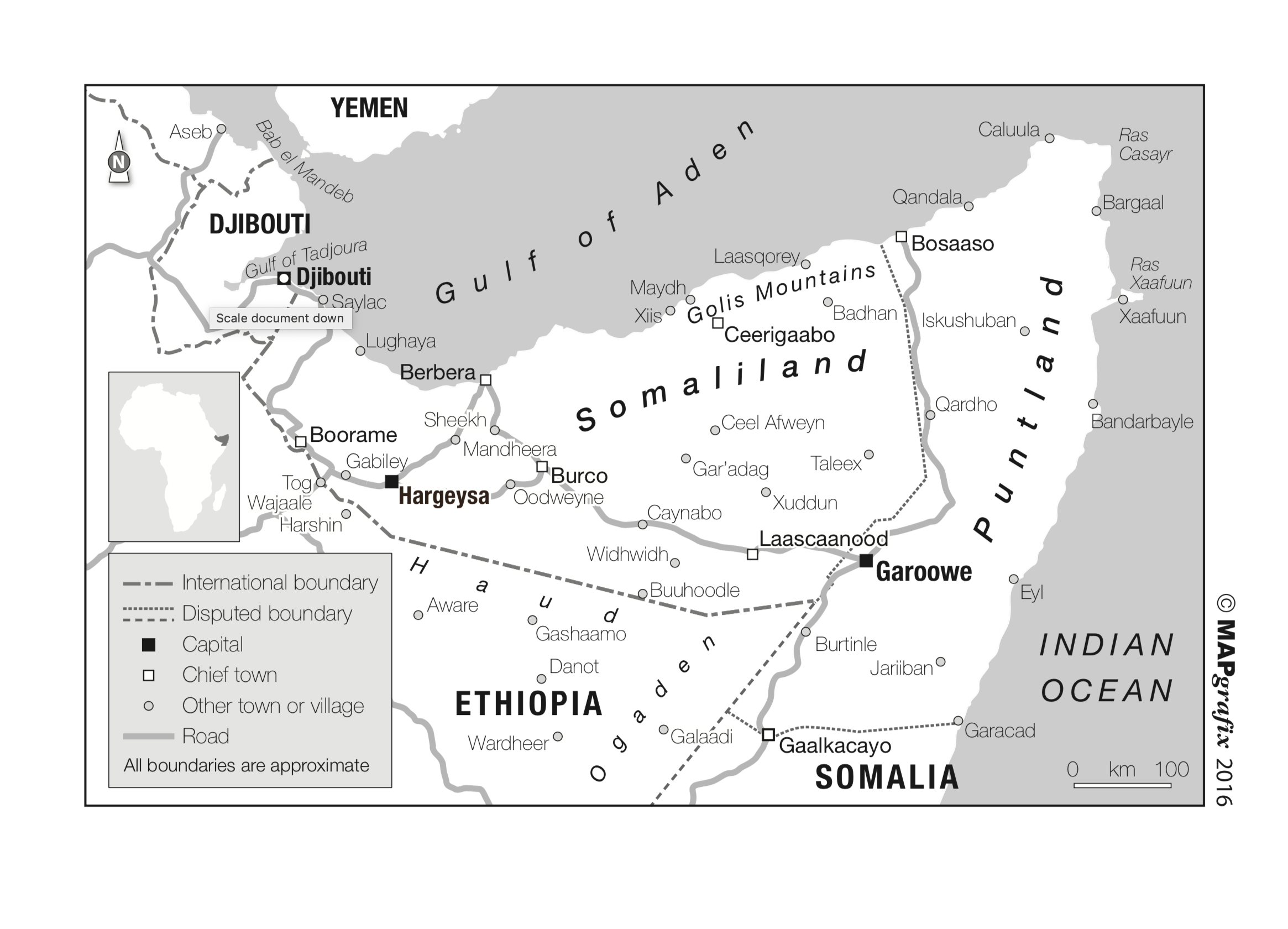

What makes the local crisis potentially important beyond the context of Lasanod or the Sool region is that for decades, Dhulbahante in the area around Buuhoodle (in Togdheer region) in much of Sool region and in parts of Sanaag region have stressed that they do not support Somaliland’s independence as a state. On the one hand, Dhulbahante clan leaders, together with elders from all other clans in the northwest and with representatives of the Somali National Movement (SNM), met in Bur’o in May 1991 to discuss the peace and decide about the political future of the region. Dhulbahante leaders finally also signed the agreement that contained the declaration of independence of Somaliland, in line with the boundaries of the former British Protectorate of Somaliland. This meant that Lasanod was included. On the other hand, many Dhulbahante early on distanced themselves from Somaliland as political project. In 1993 they set up their own clan administration in their areas. In 1998 they supported the establishment of Puntland, an autonomous regional state that challenges Somaliland’s claims to the regions of Sool, Sanaag and the areas around Buuhodle. Puntland took control of Lasanod in 2003, but was chased away by Somaliland forces (in cooperation with some Dhulbahante militias) at the end of 2007. Subsequently, however, Dhulbahante set up their own counter-administrations and militias, which were first called Sool, Sanaag iyo Cayn (2009–12) and then renamed as Khaatumo State of Somalia (2012–15).

In the past years, particularly after 2015, the administration of Somaliland in Dhulbahante areas, including Lasanod, gained some acceptance. New government infrastructure was built (this had started moderately already in 2010), with the Dhulbahante diaspora investing in the local economy, particularly in education and health care in the urban centres. Yet, all this did not convince the majority of the clan members to full-heartedly support the independence of Somaliland. The enthusiasm of Dhulbahante to engage in Somaliland politics was also hampered by the fact that since 2010, politics in Somaliland became increasingly clan-based. Central positions in the political parties and the administrations went predominantly to the Isaaq, even beyond their demographic share, which is around two-thirds of the overall population. The political narrative in Somaliland’s centres (Hargeysa, Berbera, Bur’o) reflected this favouritism, exclusively featuring Isaaq history as the “history of the state”. This included the British colonial history celebrated by many Isaaq today, featuring prominently the anti-regime struggle in the 1980s plus the suffering of civilians at the hand of the Somali army until 1991. This, however, is partly diametrically opposed to how non-Isaaq, especially Dhulbahante, prefer to narrate their political history.[4]

. The current situation

After the demonstrations and shootings in Lasanod in early January, many families left the city. They took refuge with relatives in the countryside or went as far as Garowe or Galkayo in Puntland. Those who made it to the countryside face dire living circumstances since it is currently dry season (Somali: jilal). This means there is already a lack of water and food in the countryside, which is now aggravated by the refugees. Still, a considerable civilian population (more male than female, more young than old people) remain in town. Many have taken up small arms and demonstrated their willingness to defend their place against a potential attack by Somaliland forces. For a month now (as of early February), Lasanod is not controlled by Somaliland any more. There are, however, Dhulbahante soldiers in town who officially work for Somaliland, under the command of several local officers, the most senior of which is Mahad Ambashe (from the sub-clan Jama Siyad/Reer Warsame).

In mid-January, several high-ranking ministers of Somaliland, including the interior minister, Mohamed Kaahin (Isaaq/Habar Je’lo) and the commander in chief of the Somaliland army, Nuuh Tani (Isaaq/Habar Awal) came to Lasanod to monitor the situation. They took residence in Hamdi Hotel in the east part of the town, guarded by their own forces. Yet, they did not engage in visible talks with the majority of the population or their (traditional) leaders. Images being broadcasted from Lasanod at that time featured the Somali flag, which soon was also hoisted in other places in Dhulbahante-land, including the small towns of Hudun and Taleh. The situation in town remains calm.

In the second half of January, all 13 of the highest traditional leaders (Somali sing.: isim, pl. isimo) of Dhulbahante plus one of the Fiqishini[5] clan have come to town. Except for one, Garad Jama Garad Ismail (Jama Siyad), they had spent the past years since the 2007 capture of Lasanod by Somaliland troops outside of town – either in the countryside close to their respective sub-clans or in Garowe, the capital of neighbouring Puntland (some 140 kilometres east of Lasanod). The clan leaders were welcomed by all inhabitants. Moreover, a committee of 33 senior inhabitants representing the various branches of Dhulbahante and Fiqishini was established to lead consultations. The clan leaders, elders, religious leaders, business-people and intellectuals of Lasanod are involved in these consultations that officially began on Saturday 28 January 2023 and are expected to lead to a decision on the way forward for Dhulbahante in the coming days.

On 30 January, President Muse Bihi’s widely broadcasted speech before the government blamed “terrorists” for the unrest in Lasanod. This was received with contempt by the traditional leaders in Lasanod. They blame the Somaliland administration for the insecurity in town. For them, the reference to terrorists, which clearly hints at Al Shabaab, is a strategy to discredit the political movement among Dhulbahante which expresses its allegiance to Somalia (rejecting Somaliland’s secession). Meanwhile, Somaliland supporters in their public statements try to present what is currently happening in Lasanod (and some other places in Dhulbahante-land) as irrelevant, as an expression of a minority-position or as an upheaval produced by foreign or terrorist elements. Yet, against the backdrop of the long history of the majority of Dhulbahante rejecting Somaliland’s independence, the “blue revolution” (i.e., waving the flag of Somalia), is more credible than Somalilanders wish to accept.

Already in late December, Hassan Sheikh Mohamoud, the president of Somalia, voiced his concern about the killing of civilian demonstrators in Lasanod. Yet, the Somali government in Mogadishu is not in a position to intervene. It is involved in battling Al Shabaab in central Somalia and has no power to take a stance in the north, where Somaliland established its de facto independence long ago. The governments in Hargeysa and Mogadishu are supposed to hold talks on their future relations. These talks are currently on hold, not least because of the concern of Hassan Sheikh Mohamoud with Al Shabaab. The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) held a meeting in Mogadishu on 1 February 2023, to discuss joint efforts to defeat Al Shabaab (and prevent its fighters from infiltrating neighbouring countries). In this context, news emerged that Ismail Omar Gelle, President of Djubouti, offered his services as mediator between the Dhulbahante leaders and the government of Somaliland. Yet, on 2 February, the spokesperson of the committee in charge of internal discussions in Lasanod, Chief ASqil Abdirisaq hassan Falaluug, rejected this mediation offer. He expressed the position of the committee and the clan leaders that negotiations could only begin after Somaliland forces withdrew from all Dhulbahante areas.

. Different forms of governance: traditional versus state rule

The complex situation in Lasanod illustrates two different systems of political order in place. In the centre, in mainly in the Isaaq-inhabited areas between Hargeysa, Berbera and Bur’o, the state administration had grown into an effective factor of ordering ordinary people’s lives. Police, judges at government courts and other government officials are regulating the daily affairs of many citizens. The state is considered legitimate in these areas. Yet, in the Dhulbahante and Wrasangeli inhabited lands in Sool, Sanaag and around Buuhoodle, the Somaliland state (or any other state, for that matter), has not taken root over the past 30 years (since the collapse of Somalia in 1991). People there are used to self-governance, which is administered by local traditional authorities, clan leaders and sheikhs. The logic of political conduct is quite different between state and clan-governance. In the Dulbahante lands, the elders and clan leaders enjoy more respect than ministers or military generals.[6] Hence, the difficulties of the Somaliland ministers sent to Lasanod in mid-January to reach out to the people and to steer the political process in town with any degree of success. This means also that the government in Hargeysa and the leaders of the people in Lasanod currently, and will in the near future, talk past each other. The logic of Hargeysa is: Lasanod is in our state-territory, we have to control it (since we are the Government). The logic of the people in Lasanod is: we are a clan that mainly opposes Somaliland, we follow our elders, and isimo, the Somaliland administration, should respect our wish to self-governance. It is hard to imagine a compromise at the moment.

. Threat of large-scale violence

The current situation, because all sides are talking past each other, bears a high risk of further escalation into large-scale violence. All sides have been amassing arms over the past weeks. The government in Hargeysa already had stationed considerable parts of its army including heavy armoury and tanks in the area. In the past weeks, reports and video-footage circulated in various media outlets that Somaliland is reinforcing its troops near Lasanod. While it is difficult to state how many soldiers exactly are positioned near Lasanod, it is safe to assume that they number several thousand. More tanks and technicals (pick-up trucks with heavy machine guns mounted on top) have been brought to the area in recent days. On the other side, Dhulbahante as a clan, seek to increase their defensive power. It is hard to know how many and what type of weapons exactly are in the hands of clan members should Somaliland attack. It is reported that through areas south of Lasanod, not controlled by Somaliland, a considerable amount of small arms, but also some technical and heavy machine guns, have been brought into town. Besides, Lasanod residents have never been disarmed by the Somaliland administration. Thus, small arms have already been around before the current crisis. In case fighting between the Somaliland army and Dhulbahante organized as clan-militias would start, what would happen is unpredictable – except that there would likely be a high number of casualties, including, likely, civilians who are still in Lasanod.

There is also a possibility that, should the fighting continue over days and should Dhulbahante loose many men, neighbouring clans who are related to Dhulbahante, such as Warsangeli (in eastern Sanaag), Majeerteen (in Puntland) or others might try to assist Dhulbahante, which would lead to further instability in the wider region and a higher number of casualties. It is unlikely that Puntland will directly get involved, since the government in Garowe is not prepared for a fully-fledged military confrontation with Somaliland forces. Moreover, such an escalation of violence would destabilize the whole of northern Somalia. Should a military build-up become visible on the side of Puntland it could provoke Ethiopia’s political interference. Ethiopia, currently weakened by internal conflicts, is still a regional super-power and has considerable influence in Hargeysa, Garowe and Mogadishu. Nonetheless, there is a possibility that Ahmed Karash, vice-president of Puntland and Dhulbahante/Naleye Ahmed, will clandestinely send considerable military support from Puntland or though his private channels. His sub-clan has positioned a considerable number of technical in the area east of Tukarak, an important control-post along the tarmac road half-way between Lasanod and Garowe.

Horn of Africa region borders. Produced by MapGrafix London. Copyright Markus Hoehne.

At the moment, there is a deadlock between many Dhulbahante, especially those in Lasanod, and the Somaliland administration. The committee in charge of internal negotiations among Dhulbahante (including the clan leaders and others) will soon publish its findings, which most likely will be presented as “the will of the people”. The danger is that a “maximal demand” from a Dhulbahante point of view could be requesting Somali forces to vacate Dhulbahante-lands, which many locals in Lasanod consider as “occupied” by Somaliland. In reaction, the risk is that Somaliland refuses and thus violence erupts is high. Muse Bihi is himself under pressure. He faces stiff opposition from Wadaani, the opposition party that controls the House of Representatives in the parliament. To stabilise his rule, he has to play the “Somaliland nationalist” card making it very unlikely that Hargeysa would react positively to demands coming from community representatives in Lasanod to withdraw its army further to the west.

. Ways forward

On Monday, February 6th2023, fighting erupted in the east part of Lasanod, around Hotel Hamdi. Somaliland forces and local militias are shooting at each other. Somaliland reportedly used also heavy weapons. The number of casualties is not known. The situation is escalating. The most important question at the moment is how further violence can be prevented. There are many civilians in Lasanod. Ongoing fighting between Dhulbahante forces and the Somaliland army will almost certainly produce a high number of civilian casualties, including women and children who are still in Lasanod. Moreover, a military confrontation will likely lead to considerable destruction of property and will produce thousands if not tens of thousands refugees from Lasanod and the surroundings. Besides, fighting will produce more refugees and a considerable humanitarian crisis in the middle of the drought season. In the mid-term, the escalation of violence will result in the lasting disruption of relations between Dhulbahante and the government in Hargeysa. It is hard to imagine how, after many more casualties, a relationship of trust and cooperation could be established between the two sides again. This would mean that Somaliland would have even more problems to stabilize its rule in the eastern territories, where Dhulbahante but also Warsangeli reside, who are related to the common ancestor named Harti. If Hargeysa does not plan an “ethnic/clan-cleansing” campaign, it must negotiate with those opposing its rule in the east.

External actors, including representatives of the United Nations and diplomats from countries cooperating closely in some regards with the governments of Somaliland and Puntland should use their influence, particularly in Hargeysa, to demand a peaceful solution to the current crisis. In fact, it would be very helpful if Somaliland forces could withdraw to some degree and leave Dhulbahante until tensions subside. After some time, it is likely that Dhulbahante, who are economically not self-sufficient and are dependent on trade with the east and the west (along the tarmac road which is mainly controlled by Somaliland) will realise that a radical stand on political autonomy is not viable. This would then open new avenues to begin talks between the Somaliland administration and Dhulbahante. It should also be clear that there will not be an easy solution to the misunderstanding between both sides. Both have developed into very different political directions since the early 1990s. In the long run, a well prepared referendum in eastern Somaliland over the question of Somalia versus Somaliland could be an option to allow for international recognition of Somaliland with or without the Dhulbahante (and Warsangeli) areas included.

. EndNotes

[1] Hoehne, Markus V. 2015: Between Somaliland and PuntlandMarginalization, militarization and conflicting political visions, Rift Valley Institute, pp. 98–99.

[2]Telephone interview with resident of Lasanod.

[3]Telephone Interview with a health worker at Lasanod hospital, 25 January 2023.

[4]For more details, see Hoehne, Markus V. 2011, ‘Political Orientations and Repertoires of Identification: State and Identity Formation in Northern Somalia’. PhD Dissertation Martin-Luther Universität Halle-Wittenberg, chapter 8.

[5]The Fiqishini are originally a sub-clan belonging to the Hawiye/Habar Gedir clan residing mainly in central Somalia. Yet, they moved to the north and were integrated as “guests” into the Dhulbahante clans some centuries ago.

[6]Hoehne, Markus V. 2018: ‘One country, two systems: Hybrid Political Orders (HPOs) and legal and political

friction in Somaliland’, in Olaf Zenker and Markus Virgil Hoehne (eds),The State and the Paradox of Customary Law in Africa. London: Routledge, pp. 184–212.